Alexei Ratmansky: 'The question of the future of Russian art is not relevant now'

Choreographer Alexei Ratmansky is in many ways a fascinating man. A world traveller who at the age of thirty-six became artistic director of one of the world's most prominent ballet companies, the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. A ballet archaeologist who in recent years has seen himself staging historically informed productions of classical ballets. A socially active personality who refused to remain silent after Vladimir Putin and his criminal regime invaded Ukraine.

To arrange an interview with someone so busy and in demand with the world’s media seemed to me to be, at the very least, phantasmagorical. But, social media has no filter, so one evening I took my chances. And Alexei Ratmansky really did respond. A little late, but all the more willing. Thus, a transatlantic conversation was born in which we discussed the formative moments of his career, his views on current political events, and his specific, fascinating work with dance notation.

When I was reading about your childhood, I learnt that your father was a gymnast which then led you into a dance career? Why dance, though? Why not be a gymnast, an athlete yourself?

I started dancing almost by accident, by chance. Yes, my father did gymnastics so I did it as well when I was a kid. My mum is quite a musical person, she loved to sing and to dance. And as a young child, I always used to move when I heard music playing and saw dancing in our house. I didn’t really take any ballet classes before entering ballet school.

Which was the famous Bolshoi Ballet Academy. Why did you, or rather your parents, decide to make you attend a school in Moscow when you were living in Kyiv, Ukraine, which has its own fair share of great ballet schools?

My father used to go to Moscow for work and he took me with him sometimes. One day, we saw the announcement of the entrance exams for the ballet school and since I was always dancing all over the space, we decided to go for it. I succeeded and realised that dance is something I really wanted to do as a career. My dad, on the other hand, was rather opposed to it, he was not sure there would be a future for me in ballet but I insisted.

Looking at your career, at the beginning you were always on the move. You graduated from Moscow, went back to Kyiv, then to Canada, and then to Denmark. Was it important for you to keep moving?

I graduated in 1986 and three years later the Soviet regime fell, the whole world suddenly opened up for me and I was one of those who felt they needed to go to new places, see and experience new things. I was always curious and rather ambitious, so when a new opportunity presented itself, I went for it. It was also eye-opening! I realised that what I know may be important, but it’s not all there is.

In your dancing years, you encountered the Balanchine ballet school in Canada, then the Bournonville ballet school in Denmark. How difficult was it for you to adapt to these new styles, coming from the Russian school of ballet?

First of all, we need to clarify what ‘Russian ballet school’ is and how it differs from ‘Soviet ballet school’. The Russian school was influenced by French and Italian masters during the Imperial period . After the revolution, many teachers and dancers left Russia and they usually tried to preserve the style they were taught. The situation was different in Soviet Russia. Agrippina Vaganova became the leading figure and rather dramatic changes started to emerge. People wanted to update the style and the technique, to make it relevant for new audiences and the new ideology. When I was talking to Mikhail Baryshnikov many years later, he told me that Balanchine was very opposed to these changes. It is also rumoured that Tamara Karsavina described the Bolshoi male dancers as circus dancers. But I haven’t found the source of this supposed quote yet, so take it with a pinch of salt…

When I was studying at the Bolshoi Academy, I was lucky that my professor, Pyotr Pestov, was really interested in older styles, in particular the Cecchetti technique. He spent his time researching and going back through the archives, so our schooling was a bit different.

So it was easier for you to transition into the new styles?

When I first saw Balanchine’s ballets performed by Western companies touring in Moscow, I was fascinated. His style is immensely musical, which inspired me as a young aspiring choreographer. I also felt it would suit me better as a dancer than Soviet bravura. That’s why I chose to go to Canada, where Balanchine’s ballets featured heavily in their repertoire and for the first time I experienced classes where his technique was employed. I quickly saw changes in my body. Thanks to Balanchine, my muscles elongated, which has changed not only my appearance, but my dancing as well.

And what about Bournonville?

The Bournonville technique seems very close to the old Imperial style and yet I struggled with it much more than with Balanchine. With Bournonville, you cannot show force, it all has to appear completely effortless. I spent 7 years in Copenhagen studying this style, taking classes, and I was very eager, but seeing myself in old videos, I still feel like I am watching a stranger trying to dance Danish. But I loved the style nonetheless and I think it influenced me greatly as a choreographer.

Were you always this open to different approaches and styles?

In Soviet Russia, there was this attitude of self-importance, the notion of ‘we know best’ and that is what we were all brought up with. When I came to Canada, I was very resistant to British versions of the classics, but after a year I started to open up more and more and I realised that I could combine my preferred aspects of each style.

You mentioned the ‘Soviet attitude’. I know you are no longer in Russia or Eastern Europe, but has it changed over time? Are dancers, teachers, and choreographers more open nowadays?

I have no idea about attitudes today, so I won’t speculate. During my time at the Bolshoi, I brought in Western ballet masters and teachers. There was a lot of resistance, but also a great desire to learn new things, especially among the younger dancers. But now with the return of anti-Western hysteria and Western choreographies slowly disappearing from the repertoire – I don’t know what will happen.

You mentioned Russia and its culture, something that is much discussed at the moment due toRussia’s war in Ukraine. What is the future of Russian art in your opinion? Because if we look at the ballet world in particular, the Russian influence is huge. How should we approach this, in your opinion?

This war that Russia started on the 24th February, 2022 is an imperialistic, colonial war which has already caused the death of half a million people. I am not even talking about the destruction of cities, the economy, and of nature. Many people agree that it is also a genocidal war since in the occupied territories they had banned the Ukrainian language, deported Ukrainian children to Russia, and destroyed Ukrainian cultural institutions and historical landmarks. Russian culture however (with minor exceptions) continues this ‘feast in time of plague’ — performing, singing, dancing, making films, exhibitions and festivals, all whilst completely ignoring (or worse - supporting and glorifying) the horrible war crimes that Russia has committed in Ukraine. To ignore a war of that magnitude? To support the genocide? This is a complete failure of a culture that was once famous for its humanistic ideals. It’s a catastrophe… I think, to have a future, Russian culture must look this catastrophe in the face and understand what Russia has done. Similar to what Germany and German culture went through after World War II.

No one is going to stop performing Russian ballets or Russian music, they are part of the world’s heritage. As for Russian artists (or athletes) today – I strongly believe that those who have not publicly condemned Putin and the war should not be invited to perform outside of Russia.

You mentioned Russian cultural figures and their speaking or not speaking out against the war. I particularly liked your quote where you stated that ballet artists do not only have nice legs, but a heart and mind as well…

It is very diminishing to think of artists as people who should only be concerned with their art. There is this view of ‘keeping politics out of art’, but that is nonsense. It is not the case, and it never was! Same with sport. Take the Olympics – they are inherently political from the start of the opening ceremony, when we see national flags on the athletes’ uniforms! The West should be much stricter on this and drop the double standards.

Not to play devil’s advocate here, but when one thinks of ballet dancers and their education, it is somehow limited, especially in terms of sociopolitical issues. So when one sees a 20-year-old ballerina saying, “I do not know enough to have an opinion on such a complex matter”, one almost understands where she is coming from…

Any 20-year-old ballerina knows what war is, what death is, don’t they? This is the issue with our (i.e. Soviet and post-Soviet) upbringing. We were taught to be silent, not to have any opinions, or at least not to voice them. It goes back for generations and it is horrible. Even me, I’m still fighting it. The moment I realised I have a voice and can change something was during presidential elections here in the US, when we voted for Biden over Trump and won. And then it was the 24th February 2022, I was sitting in a taxi on my way to the airport to leave Russia and I realised once again that I have a voice, that I have an influence, that I can be heard and listened to. And also, that I am from Ukraine, whilst being known around the world as a Russian choreographer, so I found myself in a position of responsibility and knew instantly that I couldn’t be silent. The war waged in my own home opened my eyes. I regret that I didn’t speak out earlier when Russia invaded Georgia in 2008, when it annexed Crimea in 2014. I regret that I went back to work at the Bolshoi and Mariinsky after 2014. At times like that, one faces a choice and I made the wrong one, even though professionally I am proud of the work I did there. But it’s now clear to me that the silence and opportunism of the cultural elite led to this tragedy.

You are also one of the key figures in the United Ukrainian Ballet company that was established by Dutch ballerina Igone de Jongh. How do you find support for the company and for Ukrainian art in general? Is it changing over time?

When I was approached by Igone to contribute something to the company’s repertoire, I was extremely grateful because I felt that I was doing something ‘real’. I believe it is crucial for this company to continue performing and, in doing so, reminding the world about what is being done to Ukraine and to our families and friends there.

We all see horrifying pictures from the war on TV, social media etc. But it is different when you are sitting in a theatre, watching people fresh from this horror, some of them with tragic stories, performing live in front of your very eyes. Each show ends with all the dancers on stage singing the Ukrainian national anthem, which intensifies the experience even more.

I have to mention one particular performance in Washington where a Ukrainian soldier, Oleksandr Budko, was present in the audience. It was his first time at the ballet and he came backstage afterwards and said, “I would love to dance!” A few months later, we were performing in California and this soldier, who had lost both his legs, was actually dancing on stage. Dutch choreographer Emma Evelin made a special piece called Airlift for him and the company. It was one of the most moving things I have ever experienced in my life.

You staged your Giselle for the company. Why did you choose this ballet?

Not long after I was asked by Igone to work with the company, we were approached by producer Paul Godfrey. The London Coliseum had a free week and wanted to dedicate it to a Ukrainian ballet show. I chose Giselle because the dancers from the company were familiar with it, the ballet is not Russian by origin, and it is a great dramatic story. Moreover, my version revives the original ending – with Albert continuing with his life, learning from his mistakes, going through catharsis, and being forgiven by Giselle’s spirit, which sends an important message of hope and of life going on.

Giselle is one of your many historically informed ballets. What sparked your interest in them?

I have always been interested in classical ballets and was eager to put my own stamp on them. But one of the most significant moments was in Australia where I was staging my new ballet as part of a double bill with Wayne McGregor. Whenever I had the time, I went to the studio to watch him work and I was in awe. His vocabulary was so edgy, so contemporary, and I felt then like me and my neoclassicism was rather dated. But then my friend told me, “Alexei, that is your strength!” And I realised that it may be true.

What made me interested in historically informed productions? When you want to do a classical version of Swan Lake or Sleeping Beauty etc., what can you do? You watch a production by the Bolshoi, by the Mariinsky, maybe by the Royal Ballet and then you combine the aspects you like. Well this didn’t make sense to me. I wanted to understand the ballets better, to discover more about their origins. Which led me to notation, to old scores, production books, and various other sources. But I have to admit, working on such a production is much more difficult because many of the sources are kept in the Russian archives… I do have my materials that I have collected over time, so we’ll see how it goes in the future.

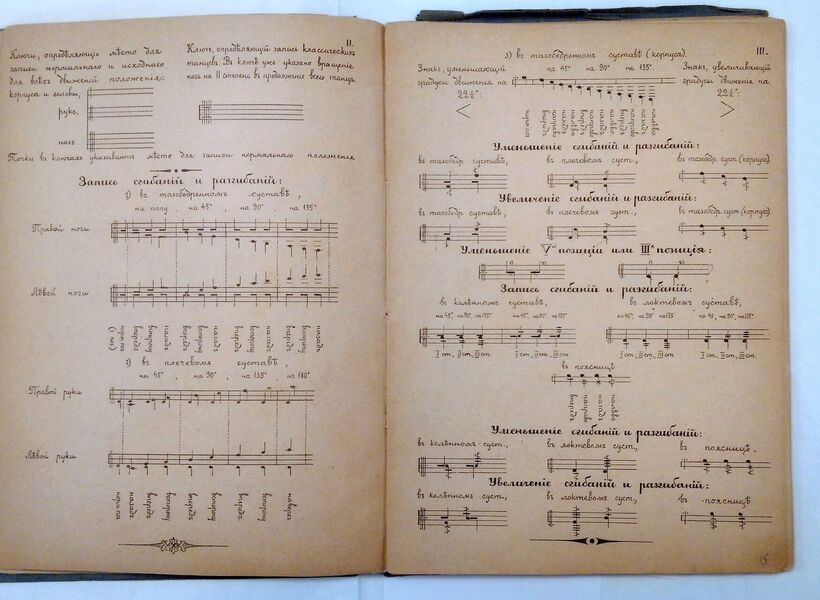

The crucial thing when staging these productions is the knowledge of Stepanov movement notation in which the old Petipa productions were notated. What is the most challenging part of working with the choreographic scores?

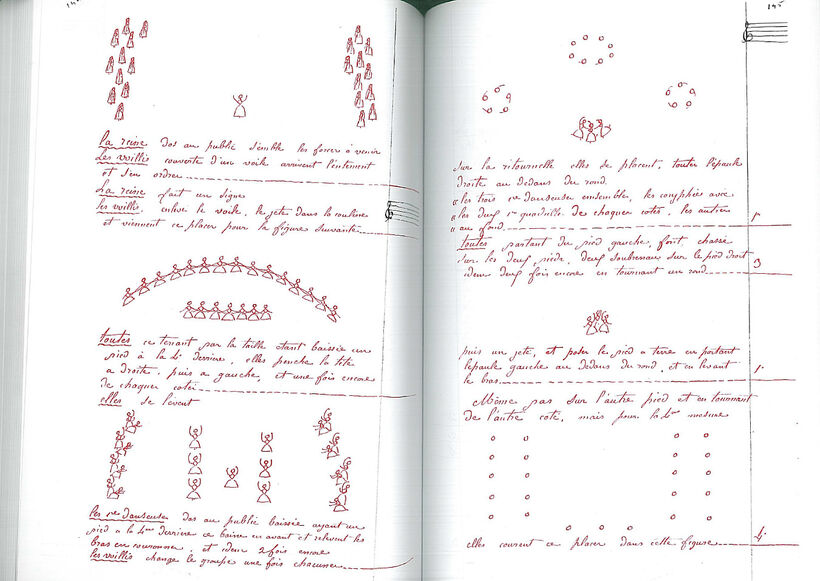

The choreographic scores are like a treasure trove; they gave and taught me so much! They are here, they are open, and nobody seems interested enough to benefit from them— I find it almost funny. As a choreographer, the notations enriched my vocabulary and inspired me immensely. I felt like I was following the great masters and learning from them, something which I believe to be vital to the choreographer’s job. We cannot say these choreographic scores show the ‘real Petipa’ because they were produced by other ballet masters and we know Petipa himself wasn’t too fond of notation. Nevertheless, it is the closest we can get to his productions and choreographies. I also have to mention the notations by French choreographer Henri Justamant which are greatly inspiring and which I used in my production of Giselle. Looking at the old materials, you realise how clever theatre makers were! And not only choreographers, but technicians as well. Take the destruction of the temple in Act IV of La Bayadère. When I staged the ballet in Berlin, they were unable to do it, so we had to use a video instead, which wasn’t the best option.

The most difficult part of working with the notation scores is when there is a gap. Because if you are putting together a complete production, you have to fill them. Finding a way to do that in style is quite challenging. You have to find what I call ‘complex simplicity’. Choreography back then was not overly complicated, but it was not banal either! Finding a balance that is engaging and harmonious is the real challenge.

What other sources are you using, apart from the notation scores?

Various ones! There are rather a lot of old films and videos. Photographs help as well, along with period designs and drawings. The more you see, the more you understand the time and the style and the archival sources seem to be endless! But I must admit that the war has cooled my interest in this work for the moment…

You have made quite a few historically informed productions. Paquita, Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, La Bayadère, Harlequinade, Giselle… Why did you choose these ones?

I was usually asked by the company that was interested in my work. In Zurich, they wanted Swan Lake, in Berlin, they asked specifically for La Bayadère, the Bolshoi wanted to change their Grigorovich production of Giselle. With Harlequinade it was a different story, I asked the American Ballet Theatre (ABT) myself if we could do it. I loved the music and there was enough information about the ballet, so I wanted to give it a go. Harlequinade was restored purely from the notation scores, which was such satisfying work!

When talking about ballet reconstruction or historically informed productions, we shouldn’t forget Sergei Vikharev and his work in the field.

I admire his work greatly and have seen his productions of Sleeping Beauty, La Bayadère, The Awakening of Flora, and others. But I don’t like combining the old imperial era with the Soviet tradition, which was something Vikharev did. For me, I don’t think they go well together. But I know that it was not easy for him coming to the Mariinsky for the first time with his vision of the old imperial style, because many people were vehemently against using the choreographic scores and the notations.

Would you like to come back to some of your productions and maybe change them a bit based on the experiences from your other productions?

I would like to come back to Sleeping Beauty and La Bayadère. I think a change in design and costume would help them. I didn’t work with the period costume designs because I didn’t believe they were necessary to make the production work. And I felt that maybe a more contemporary approach to costumes could act as a bridge between the historical sources and contemporary audiences. What I realised later was that Petipa choreographed not only the dance, but the colours as well, which was something we overlooked in La Bayadère. I think the best costumes are in Harlequinade. They were made by a contemporary designer named Robert Perdziola, who was influenced by period designs yet made them his own.

More recently I have become less pedantic about the period style of dancing… I think I struck the right balance with Giselle — still respecting the notated choreography but making the coordination of the steps more accessible to the dancers

I have to admit I always loved the style and aesthetics of your productions and I noticed quite the dramatic change with Giselle…

What made me question the style and my approach to it the most was how much the dancers struggled with the technique. Because the imperial way of dancing is so alien to them, it goes against their habits, against what they were taught, and not all of them are willing to learn it. And you rarely have enough rehearsal time for them to adapt to it, which makes it even more challenging.

Giselle is a special case, because it is not an imperial ballet, but a story that is much older. And when you work with pre-imperial sources, that becomes evident. The only part of the ballet that is purely for show is Giselle’s variation in Act I and you can tell it was added much later. Everything else, every dance number is about telling the story.

Speaking of storytelling — one can hardly imagine 19th century ballet without mime. Because without the mime, the story simply does not work. But how should we use mime today? How can we do it properly, so that people understand it and don’t find it outdated?

First and foremost, it needs to be done well! You have to direct the dancers so they know what they are saying, why are they saying it, and to whom. And when done right, it can be very impressive. You need people who can really act, who are naturally expressive, and can use not only their face, but also their body to communicate. But it is hard work, so you need to take your time with them!

The steps and choreography are notated in the choreographic scores, but you don’t find exact gestures for the mime sections. How do you work with that?

If you are lucky, you can find information in old musical scores. But I think the mime should be done from a contemporary point of view. The language of the dance should not be compromised, but the mime needs to be exciting and understandable, so a contemporary approach can help a lot in this regard. It is a pity that such a crucial part of these old ballets was destroyed over the years by both Soviet and Western productions… The original structure disappeared and it all became a mush of virtuoso variations to impress the audiences with pointless tricks. The stories suffered greatly as a result, meaning that people think, “oh, it is just an old ballet, so it doesn’t make sense". But that’s such a misconception!

You have staged your productions for many companies – from the Bolshoi, to Munich, to the ABT. Is there a ballet company that is better suited to the old style of dancing?

Probably La Scala. There is something in their dancing and in the Italian school that makes it sparkle.

I know you said the war lessened your interest in reconstructions, but do you have any projects coming up of this type?

I started a project of recording selected Petipa variations with four dancers — Olga Smirnova, Maia Makhateli, Shale Wagman, and Antonio Cosalinho. We have already made twenty and I would love to do more but we need to find funding in order to continue our work.

And what about a workshop on Stepanov notation so that more people can not only learn about it, but maybe even learn to read it?

I have already done some, for example in Athens this year, and I am more than open to doing more elsewhere. I think knowing the notation is important for everyone in the ballet world — from critics to dancers. They do not necessarily need to know how to read it fluently, but I would like for them not to mistake the Soviet versions of the classics for the original ones. I want them to be better informed and understand the history of their craft.

Alexei Ratmansky (1968) - born in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad) choreographer, graduate of the Bolshoi Ballet Academy in Moscow and currently resident choreographer at New York City Ballet. He spent his childhood in Kyiv, as a dancer he has worked with the Kiev National Ballet, Royal Winnipeg Ballet and Royal Danish Ballet in Copenhagen. From 2004 to 2008, he was artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet. In 2014 he became resident choreographer at American Ballet Theatre, where he worked until the summer of 2023. He is the author of original ballets such as Anna Karenina, The Bright Stream, Lost Illusions, 24 Preludes and Concerto DSCH. He is also involved in creating historically informed productions of classical ballets, including Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, Paquita, Harlequinade, Giselle and La Bayadère.