“I would hate to be a young writer now,” says former editor of Dancing Times Jonathan Gray

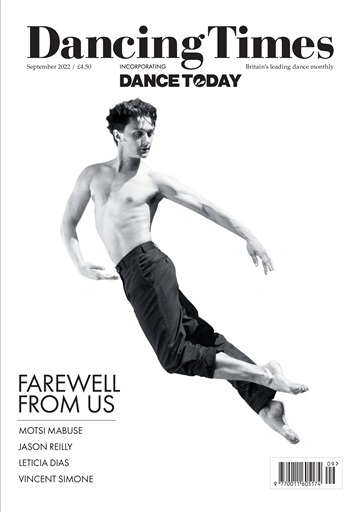

Jonathan Gray was the last editor-in-chief of the world-renowned magazine Dancing Times. Unfortunately, after the coronavirus pandemic, the magazine announced its closure with the issuing of one last edition in September 2022. After more than a century the world of dance lost an important publication which had witnessed most of the major turns of 20th and 21st century. Jon will be one of the keynote speakers at a workshop on sustainable dance criticism in October 2023, organized by Czech Dance News within the MOVE Fest Festival. I invited Jon to uncover a bit the situation around the closure of Dancing Times, but we got to talk as well about dance criticism and its viability in general.

Jon, you were editor-in-chief of Dancing Times, one of the longest-running dance magazine in history. Last year you announced the closure of all activities. What led you to this situation?

The problem was, we had carried on publishing throughout the pandemic. It seemed to me that although performances had stopped, the dance world had not. People were finding different ways to reach out to audiences, using their ingenuity with social media. We had to get a government loan to keep going. We took it with the expectation of receiving similar amounts of advertising money that we had received before the pandemic. And that just didn't happen. On the contrary, we experienced a radically reduced amount of revenue. It came to the point where we just couldn't carry on. I still had to pay the staff, the writers, the printers, the distributors...

With great regret, the directors and the trustees agreed the magazine should close. I think it's an example of a much broader picture, which strikes me now – the diminution of arts reporting in the press generally, especially dance. You can see it within well-respected national newspapers in the UK, with coverage of the arts radically reduced. Media is in an existential crisis at the moment, with readership and advertising revenues falling. So, they're looking to cut costs and, naturally, they look at the arts pages, because they're not going to cut politics, economics or sport. It's got to the point now where one of our absolutely leading Sunday newspapers has no coverage of dance at all. It's a really worrying trend. I worry about how a profession of a dance critic is going to survive. I would hate to be a young writer now.

So, Dancing Times was financed by advertising only. You had no government subsidies?

Our government does not support arts journalism financially. It sees journalism as a business, as a profit-making operation. Not that we ever made huge profits, that wasn't the point of Dancing Times. Our aim was to keep informing, educating, entertaining, and promoting the world of dance. Britain is much more like America in that way, it's based on the politics of profit and loss.

It's interesting what you said about the diminution of a dance criticism in the newspapers. That same situation is happening in America, the major newspapers are cutting down the artistic sections. But it wasn't just your magazine, it was the case of Dance Books as well, the only dance-related publisher, who also announced the closure of all its activities. Do you see any way out of this?

I don't see any way out until people actually understand the value of having their adverts in a prestigious magazine. Until that happens, it's going to be difficult. Before, people who ran marketing advertising budgets in dance understood the world of dance, they came from it, and they could see how being associated with a magazine like Dancing Times could be beneficial to them as an advertiser. They have mainly been replaced by people who know a lot about advertising and marketing budgets, but don't have any particular interest in or understanding of the art itself. It's a different world now to the one I entered in 2005. It's a very short-sighted, not far-reaching, not forward-looking world.

Often, people would come up to me and say: Oh, we're so sad about Dancing Times, we really miss it. And when I ask them if they ever advertised in it, the response was often negative. People just expect that everything is now online and free to read.

I did not consider Dancing Times becoming part of a big conglomerate publishing company, as is happening in America, to be a solution. We were always independent, and the kind of content that's within those magazines is not as good as it used to be. I'm not really interested in what dancers have in their kit bag this week… I’d like to read more about the shows that have been on in America, or what is happening there.

You are coming to Ostrava in October to the MOVE Dance Festival, and we will be talking about sustainable criticism. Dancing Times achieved many things, but I would like to know if you could go back in time, is there something you would do differently now?

I probably would have thought of a different online approach. Digital downloads of the magazine were available, and we had a website with different content from the printed version of the magazine. My aim was to encourage people to buy the magazine as well as look at the website for different things.

But we were a small company. We didn't make huge amounts of profit every year, so we didn't have a lot of money to invest in that. If we had the money, we could have done that. But I also think the digital world is very specialized, and you need to employ somebody who really understands it.

You were running a magazine which lasted 112 years, that is pretty impressive. Our magazine is only 16 years old, and I consider that a big win since we have to fight every single year for money from the government. And we could say that journalism and critical reflection is not the first category to put money into.

Arts Council England would not consider funding a dance magazine. It’s something they would consider as a purely commercial enterprise.

But on the other hand, Arts Council England is quite generous to academic dance research. Journalism has a theoretical background as well.

There used to be more funding through the Arts Council for the arts, but that's changed.

After the Second World War its aim was to make the arts available to everyone in the UK. That lasted until the 1980s, when Mrs. Thatcher came along with new way of looking at profit margins. There's a famous Oscar Wilde quote which represents this shift quite well: “They know the price of everything, but the value of nothing”.

Then, by the end of the 1990s, beginning of the 2000s, there was a big push to make the arts educational. In a way, it's become too much of a criterion now, and a lot of people feel their creativity is being stifled. It's become much more like jumping through hoops and ticking the right boxes to show that you'll get the money.

In the days of Mr. Richardson, who founded Dancing Times, things like printing and paper were incredibly cheap. It's not like now when just in the last year of the magazine's life, the price of paper went up four times.

Was editor-in-chief of Dancing Times a full-time job for you?

For me, yes. I was the only full-time member of staff, all the rest of them were part-time. It was a very small team and quite a small budget.

What do you do right now?

I'm writing occasionally. I must admit it has surprised me how many people expect you to write for nothing. You a press ticket and that's it. I think it diminishes your expertise as a writer, because if they don't consider you worth paying, anyone could write that review. What's the point of sending somebody with 40 years’ experience to write a review and then not reimburse them for it? It's been an eye-opener for me because it made me realise how many people really do not earn a living from writing about dance.

That's also the case in the Czech Republic because you cannot make a living from writing only. Also, you cannot write all the time, that is not sustainable at all.

In the old days, a dance critic would be a salaried member of staff on a newspaper. Now, most dance critics who work on a national newspaper get paid per review. If I was 30-something years old and trying to pay a mortgage, that would not be an option for me.

The other thing is that is that there are less opportunities now. If people say to me they regret the reduction of arts coverage in newspapers, I reply to them: Look, you need to write to that paper and say how much you miss the coverage of the arts. They need to vocalise it, otherwise it doesn’t count.

What's the normal pay for writing an article in Britain?

It really depends on who you're writing for. Some pay an absolute pittance, but there are also publications that have a bigger budget and a bigger readership that pay quite well. For example, I was recently paid to write an article, which was only 700 words and got paid 500 GBP. But you could also be paid for the same number of words and get 40 GBP for it. I don't think there's any kind of union agreement over the minimum price for writing.

Isn't there any kind of critics’ association in Britain?

There is The Critics Circle, but they don't involve themselves at all in payment politics. And often people are just so grateful to get anything that they don't request more. I personally wouldn't write a long article if I was only going to get paid 40 GBP for it. But there are people who will do that. And that is a problem, because people do not value their experiences.

What do you think is the future of dance criticism? Do you consider it a viable activity considering all that we discussed?

It is viable if people are still interested in reading about shows. As long as there's still a curiosity, dance criticism will survive. How and in what form, I have no idea.

Dance is so ephemeral. Not everything is recorded, so quite often a review is the only record we have of a particular performance. I found it interesting that it was always the smaller dance companies that didn't have a big budget who were the most grateful to receive a review of a show. They don't have the money to film it or make it available online or in the cinema.

I'm kind of depressed about the whole situation, but positive at the same time. It is a very difficult world we're living in, and lots of people don't have a lot of disposable income at the moment. They're simply worried about paying their bills and buying groceries. It's kind of the equivalent to how it was in the 1930s... But things can change. So, I guess that the dance world that we live in will change too.

Jonathan Gray

Jonathan Gray was born in Wales and studied at The Royal Ballet School, Leicester Polytechnic and Wimbledon School of Art. He was a member of the curatorial department of The Theatre Museum, London, from 1989 until 2005. He joined Dancing Times in 2005, and was editor of the magazine from 2008 until its closure in 2022.