It is now clear that Berlin's cultural and social scene is going through one of its darkest moments since the fall of the Berlin Wall. The cuts of an initial ten per cent and now thirteen percent that have been announced are seriously undermining independent culture in particular, but not uniquely. Under the motto #berlinistkultur, the cultural scene is mobilising on various fronts, but always under the banner of solidarity. This is the time for action and reflections on a cultural and social context that is changing.

Gisèle Vienne in Berlin: Dolls, Still Time, and Violence

Beginning during Berlin Art Week and developing over the following months, the joint curatorship of Sophiensæle, Georg Kolbe Museum, and Haus am Waldsee, presented a retrospective on the body of work of Franco-Austrian choreographer, director, interdisciplinary artist, and puppeteer Gisèle Vienne to Berlin. It included exhibitions of her puppets, the dance performance Crowd, a screening of her horror film Jerk, plus discussions, a book presentation, and a workshop.

After the presentation of her dance piece Crowd (2017), Gisèle Vienne closed her retrospective with a short but incisive speech devoted to the importance of public art and its role in safeguarding social democracy. Specifically, she underlines the extent to which cutting funding for the cultural and social sectors is a political choice that shows signs of a global deconstruction with clear fascist intent. We are running the risk of destroying, in too short a period of time, that which took decades to imagine and build.

The three cultural institutions curated the artist's work with an acute ability to read and analyse it in line with current events. Based on concepts such as time, silence, and violence, the various outcomes of Vienne's interdisciplinary artistry address the gaps between what we can define as “culture” and the world in which we live.

Crowd, Jerk, and Systemic Violence

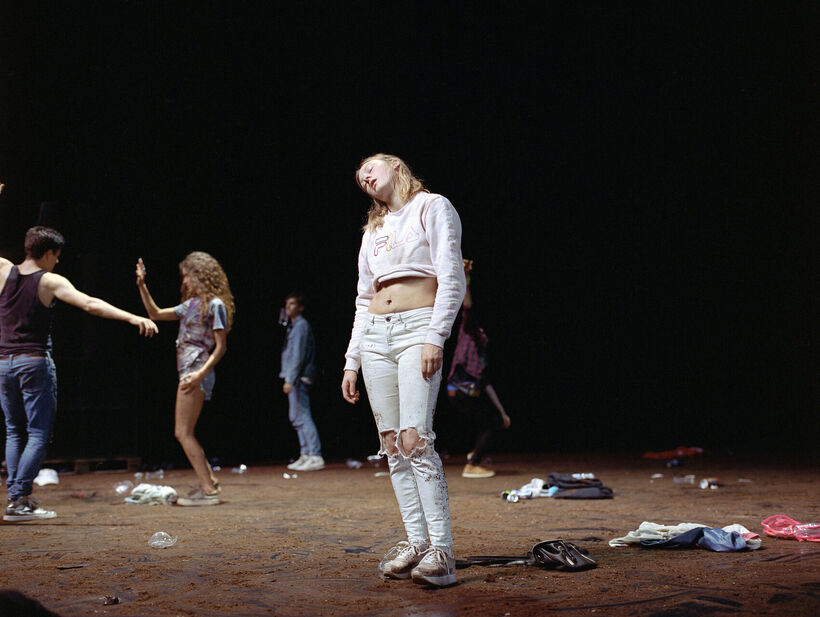

When entering the theatre to watch Crowd, a piece inspired by a rave party, the first sensation is that the party has already taken place. The soil brings to mind that of Pina Bausch's Sacre du Printemps, here already pounded and sullied with rubbish, such as remnants of cans and plastic bags. Through a side door, fifteen performers gradually enter, all well characterised from the start by their specific clothes, accessories, and attitudes. They smoke, laugh, and drink. The feeling is that of being in a film, where so many everyday actions take place simultaneously. The essence of rave is there but more in the music, carefully selected by electronic dance music luminary Peter Rehberg (1968-2021), than in the dance movements. For the many epic tracks, including some by Underground Resistance, the movements are slowed down and continuous, culminating in freezes in which all but one of the performers stop moving, before melting like ice. They spill drinks on each other, they cry, some have bloody mouths, others get into fistfights.

Only at one moment does the rave dancing explode into normal speed: the party sounds frightening, but after this “shock”, it returns to a slowed-down tempo, but with more frequent “normal speed” episodes.

Rather than the stereotype of rave culture, Vienne seems to theatricalise social emotions, such as desire, energy, the need to create a community, even in its violent aspects, with the primordial energy that underlies it. What is striking in this work is the use of time, decidedly cinematographic, ranging between long slow-motion sequences taken to the limit and sudden freezes: the actions are calibrated to the millimetre, and with time moving so very slowly, a thousand things happen. The use of slow-motion generates a kind of collective hallucination in the audience, as we watch who is doing the actions, we can see everything, as if somehow we are inside the action that we might see the mechanisms themselves. At the same time, the feeling is that the dancers are both zombies and puppets, fiercely guided from the outside.

Certainly, the element of violence is decisive and persists throughout the piece, for instance with the character of a girl who enters with a bloodied face and who often looks towards the audience with an almost frightened expression, as if searching for someone. Or the two boys who kick and punch each other.

The theme of violence returns in the crude horror-inspired genre film Jerk (2021) based on her iconic 2008 solo play in which a puppeteer/serial killer depicts violence through his puppets. Vienne attempts to unfold the mechanisms of violence, which are in fact mechanisms of power, domination, and manipulation. It is based on a piece of fiction written by Dennis Cooper, inspired by real events and presented from the perspective of the protagonist. Set in Texas in the 1970s, the story is a reconstruction of the crimes committed by serial killer Dean Corll, who, aided by two acquaintances, raped and murdered some twenty boys.

By relying on stylistic verbal and scenographic essentiality, a long-shot sequence, a few puppets, and one actor, Jerk succeeds in reconstructing the total savageness of the crimes. Vienne does not look for a climax, but immediately brings the spectator into the heart of the facts. There are no dance sequences, just slow narrative time, with the puppeteer’s (Jonathan Capdevielle) detailed actions, often of almost explicit sexual violence committed with and to the puppets of ruined teddy bears and exhausted teenagers.

Even though it appears raw and pragmatic, the otherwise thorny and topical themes, such as sexual violence, almost find a psychological aid through the theatrical writing. But I am not sure if I would want to see it again.

Houses of Dolls

In both the exhibitions Gisèle Vienne - This Causes Consciousness to Fracture - A Puppet Play at Haus am Waldsee and I Know That I Can Double Myself - Gisèle Vienne and the Puppets of the Avant-Garde at the Georg Kolbe Museum, there are predominantly human-sized puppets representing teenagers. While the first is a retrospective dedicated entirely to Vienne, the second is a transhistorical exhibition devoted to various female artists who have made the puppet a form of artistic and political expression.

The retrospective was developed specifically for the architectural spaces of Haus am Waldsee and contains life-size dolls and puppets created by Vienne over the last twenty years. These are complemented by a series of photographs by Vienne herself of her dolls and puppets, featuring half-busts of dolls, some hooded. The underlying theme is that of “emotional ruptures and crises, especially in regard to the emotions of young people” and it takes its title from a homonymous piece by composer Caterina Barbieri, the curator of the exhibition’s soundscape. The life-size dolls, dressed in oversize contemporary clothes, jeans, colourful 90s jumpsuits, and silver jackets, lay in stationary positions or on the floor as if they have fainted or are dead, in groups all close together on a bed and adjacent to remnants of drinks, or sitting facing a wall as they read, while others are lying in glass cases.

It is as if their gazes represent emptiness, sadness, the difficulty of communicating; some of their faces sport tears, others blood. The material of the faces looks like ceramic and their very lifelike appearance is reminiscent of the extreme realism of bisque dolls, a particular way of working porcelain in the late nineteenth century.

Choosing to portray adolescents as dolls is decisive. Adolescence represents that delicate phase of life where one wants to say many things, but often cannot or is not heard. At the same time, however, there is immense potential for discovery and imagination. To see this phase portrayed in extreme stillness and through lost looks is powerful, like a slap in the face.

On the other hand, at the exhibition at the Kolbe, in addition to the photos of dolls positioned in outdoor settings, the human-sized figures are mainly placed standing and in groups. Upon entering the large hall, where the glass windows reign supreme, it is in fact not immediately obvious that they are not real humans.

As previously mentioned, here we also see exhibited modernist puppets in a trans-historical encounter with female avant-garde artists, active between the two world wars, such as Aleksandra Aleksandrovna Ekster, Valeska Gert, Emmy Hennings, Lotte Pritzel, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Puppets were a form of artistic expression with an extraordinarily subversive potential for political and social critique, where they could assert their female voices. At the same time, puppet theatre offered an excellent space for interdisciplinary experimentation, as it opened up opportunities to work on the borderline between disciplines such as painting, sculpture, and choreography.

The marionette and the puppet have been part of the artistic and cultural background since the dawn of time. They often take it upon themselves to speak of all that is socially aloof, somehow they represent symbols of another dimension of existence, they tell the story of a world free of the weight of human consciousness, they embody the inexplicable.

For Vienne, the puppet or doll is a powerful tool to question models of perception. In fact, like her dancers, dolls are anthropomorphic objects, but they speak silently and allow themselves to be observed, capable of resisting time. They represent absence. As Vienne writes, with dolls, the “ultraviolent process of disembodiment is complete”.

Her dolls appear alienated. Motionless, they give off the sense of being observed, they are like architectures that create a block of time. With a grotesque sensibility, they represent that other being. While they are there, standing still or lying down, they live in their own world, somewhere between their role as protagonists in the museum and in the world in which we live. Somehow, we feel them close by, yet they also instill a certain awe and wonder.

Written from the various events dedicated to the work of Gisèle Vienne, various institutions in Berlin, autumn 2024.

Crowd

Conception, Choreography, Scenography: Gisèle Vienne

Assistance: Anja Röttgerkamp, Nuria Guiu Sagarra

Music Selection: Underground Resistance, KTL, Vapour Space, DJ Rolando, Drexciya, The Martian, Choice, Jeff Mills, Peter Rehberg, Manuel Göttsching, Sun Electric, Global Communication

Edits, Playlist Selection: Peter Rehberg, Gisèle Vienne

Sound: Adrien Michel

Light Design: Patrick Riou

Character Development Texts: The performers in collaboration with Dennis Cooper & Gisèle Vienne

Performers: Philip Berlin, Morgane Bonis, Sylvain Decloitre, Sophie Demeyer, Vincent Dupuy, Nuria Guiu Sagarra, Rehin Hollant, Oskar Landström, Maeva Lassere, Theo Livesey, Maya Masse, Audrey Merilus, Louise Perming, Katia Petrowick, Jonathan Schatz

Costumes: Gisèle Vienne in collaboration with Camille Queval and the performers

Premiere: Maillon, Thèatre de Strasbourg - Scène européenne in partnership with POLE-SUD, CDCN Strasbourg (FR), 8 November 2017

Jerk

Director: Gisèle Vienne

Writer: Dennis Cooper

Original Music: Peter Rehberg

With: Jonathan Capdevielle

With the Voices of: Catherine Robbe-Grillet, Serge Ramon

Creation of the Puppets: Gisèle Vienne, Dorothéa Vienne-Polla

Creation of Tattoos and Drawings: Jean-Luc Verna

Make-up: Mélanie Gerbeaux

Director of Photography: Jonathan Ricquebourg

Chief Editor: Caroline Detournay

Sound Engineer: Pierre Bompy

Chief Electrician: Georges Harnack

Chief Machinist: Romain Riché

First Assistant Operator: Ronan Boudier

Second Assistant Director: Brandon Luong

Assistant Director: Camille Queval

Stage Manager: Antoine Hordé

Color Grading: Yov Moor

Sound Mixing: Mikaël Barre

Special Effects: Robin Kobrynski

Filming Location: Centre National de la Danse (CND Pantin)

Gisèle Vienne

This Causes Consciousness to Fracture – A Puppet Play

Haus am Waldsee 12 September 2024-12 January 2025

I Know That I Can Double Myself

Gisèle Vienne and the Puppets of the Avant-Garde

Georg Kolbe Museum 13 September 2024-09 March 2025