Political and musical timings: Montpellier Danse 2024

The 44th edition of Montpellier Danse (22 June – 6 July 2024) took place as the Euro 24 football championships were getting under way, and a few weeks before the Paris Olympics started – so I fully expected to see some sports-themed work on the programme. But by the time I arrived in Montpellier the mood had changed, and in the event two other themes emerged more strongly for me: politics, and music.

Let us start with the politics, which was hard to avoid and easy to explain. (I hope the music angle will emerge as I write.) In early June, the French far-right Rassemblement National gained nearly a third of the national vote in the European elections, to which President Macron precipitously responded by calling a surprise general election in France. Both rounds of that election took place within the period of the festival, the first in the middle of my four-day stay, the second a few days after. Never mind sport: the immediate mood at Montpellier was all about politics.

Sometimes that was explicit: at a public discussion on “the dance of tomorrow”, the socialist mayor of Montpellier, Michaël Delafosse, drew a clear connection between the values of progressive culture and progressive politics (“what does not regenerate, degenerates”). But more often, politics became a lens that coloured my experience as a spectator – including of two works which were explicitly based on sport: Roll, by Marta Izquierdo Muñoz (part of the Paris 2024 Cultural Olympiad), and Ballet de Lorraine’s Discofoot, by Petter Jacobsson and Thomas Caley (first created for the Euro 2016 football championships).

Muñoz’s piece was inspired by both competitive roller-derby and celebratory roller-disco, and features four skaters in spangly costumes speeding about while a fifth (actress Cécile Chatignoux) acts as cheerleader, referee, coach and compere. Powered by its music, sometimes upbeat, sometimes driving, it is a sequence of scenes based around single motifs: a spinning chorus line, speed chases and thrown jumps, formation choreography, fights with air mattresses. At one point, Chatignoux gives voice to Muñoz’s motivation, explaining how skating had been an exhilarating assertion of individual freedom and rebellious energy in the wake of Franco’s Spain – a point brought up to date after the show when Muñoz herself spoke on stage to warn of the far-right dangers in the forthcoming election.

Personally, I felt these political messages were rather tacked-on, and that Roll spent more of its energies trying (a bit too hard) to entertain its audience. Strangely enough, I found Discofoot more effective in this direction, even though it is all about entertaining, and has no explicit political message. On a rectangle of fake turf in the middle of Montpellier’s Place de la Comédie, the dancers of Ballet de Lorraine separate into two teams for a game of footie, kitted out in pink or blue tops, and wearing glistening gold shorts. They’re a limber lot, high-kicking and stretching into the splits just by way of warm-up. Once the music starts (club and disco classics), you can’t stop them: it’s somersaults and fouetté turns, vogueing limb twirls, cheerleader bops, breathless aerobics, bootylicious boogie. Somewhere among all this is a football (sprayed silver, naturally), but it is really just a pretext for the dancers to show off and show the crowd a good time. They succeeded: Discofoot was tons of fun.

Yet what did I think of? The elections. Opposing sides, trying to beat each other. Performative posturing. Partisan loyalties and popularity contests. Point-scoring. Foul play. Gaming the system. There are certainly similarities between sports and elections, as between elections and theatre, but what stood out for me were the differences that Discofoot brought: laughter, pleasure, co-operation not competition, conviviality not division. It made me wonder whether music, or at least the spirit of music – which both animates our bodies and brings different parts (sounds, voices, instruments) into agreeable wholes – might offer us social ideals as well as artistic pleasures.

Musical moves and migrations

Perhaps that is reading far too much into the campy showmanship of Discofoot. Nevertheless, the idea of music as both a force that animates us and a pattern that connects us informed the rest of my festival experience. In takemehome, for example, choreographer Dimitri Chamblas teamed up with musician Kim Gordon (formerly of Sonic Youth) to create a work for “nine dancers, five electric guitars, and five amplifiers”, plus an enormous zeppelin which floats above the stage, emitting flushes of red, blue or white light upon scenes that pass largely in shadow. The opening sees some performers sitting among the audience and some audience members guided gently onto the stage, and off again – so that you get the sense that those on stage, even the diversely skilled dancers, are not just a group of “them”, but a part of “us”. It’s a nice feeling, this openness, this non-division. Not that we could move as the dancers do: they’re all impressive, highly individual dancers, each with distinct motifs and styles. The choreography sets them largely in isolation, dispersed across the stage area, though sometimes caught up in jumbling formations that rush, cluster and scatter. There are passing encounters, but these are fleeting and friable: the overall feel is of solitary, introspective beings. What brings them together, in the end, is music – more specifically, the electric guitar. One person strikes a single chord, which gradually multiplies and amplifies into a chorus of five guitarists, and a thrumming crescendo of open-stringed strums. All the dispersal and isolation, all the cryptographic solos and symbols, now seem to coalesce – like noise becoming signal – into a kind of strength and solidarity.

Outside the theatre, hanging like an ominous zeppelin in the political clouds over France, I could almost feel the threat that had been made by the Rassemblement National (not for the first time in its history) that French citizens with dual nationality could be barred from certain official positions – a dog-whistle tactic that clearly discriminated against those with multicultural and immigrant heritage, and was designed to toxify the cultural atmosphere. The example they gave may have been “Swiss-French”, but the barely concealed subtext and consequence were obvious: it was targeted against French citizens of north African heritage. Here, at a dance festival, it was impossible not to sense that this measure would also impact the workforce of dance – which, as with many sports, is a highly multinational, multiracial and multicultural field. It was heartening to see, then, that Montpellier Danse had programmed the entire Le Monde en Transe trilogy by Marrakesh-based choreographer Taouffiq Izzediou. I found it well worth watching in full.

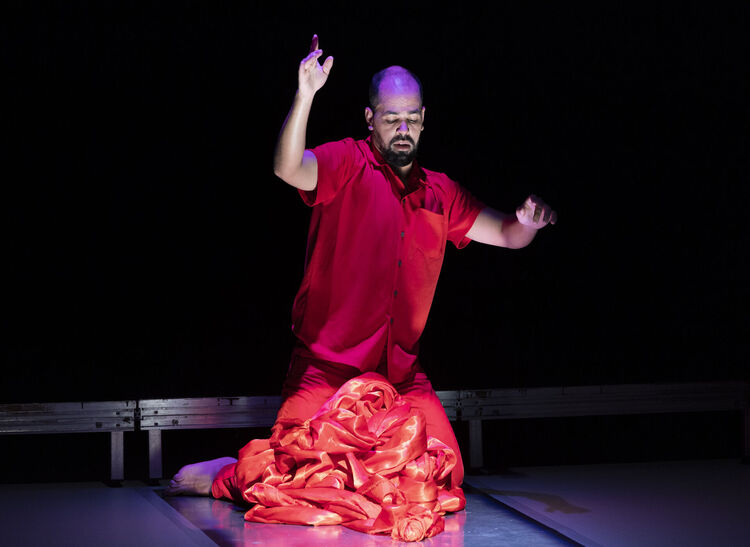

The first part, HMADCHA, is named after a 17th-century Sufi brotherhood. Sufism is associated with mystical practices that fuse music, movement and chant into pathways towards the divine, and the influence here is clear. The stage-right wall is an illuminated panel that serves as a kind of divine light, an immanence that keeps magnetising the dancers towards it (recall that in Islamic prayer, the body does not face any symbol or icon, but – more abstractly – aligns towards a particular direction). While the side wall indicates some otherworldly realm, the stage becomes the ground that the dancers inhabit, often lit like a chequerboard, as if to mark out their worldly manoeuvres. If these dimensions – one grounded in the present, the other lit from beyond – defined the work’s spatial forcefield, its temporal one was defined by cycles of sound: the surge and ebb of breaking waves, the repeated riffs of an electric guitar, the breathy drone of vocal chants, the soothing washes of piano chords.

Into this numinous world steps a single man (Hassan Oumzili), bathed in light and facing the lit wall, spine undulating and feet taking small rock-steps. Cumulatively, seven other men emerge into this terrain, navigating each other with pawn-like moves, as if on a chequerboard. The moves diversify: you sense some capoeira, some krump, some repeated actions of manual labour. There are circles and clumps, and parries of motion that send the men reaching towards and falling back from that sidelit wall, as if aspiring towards the beyond. It ends with Izzediou himself entering to lead the fraternity offstage and into the auditorium, as if out into the big wide world.

Hors du Monde (Out of the World) has a more alienated, introspective feel. It is essentially a duet for a dancer (Hassan Oumzili again) and a guitarist (Mathieu Gaborit). Initially they seem to occupy the same world, the electric guitar’s insistent thrum driving Oumzili’s footsteps, again on a chequerboard floor. Yet in the middle of the work, this world breaks apart. Gaborit faces away, turning his back towards Oumzili who – now to the sound of silence – wraps his head with swathes of cloth until the smothering turban surreally suggests both an exotic bloom and a spaceman’s helmet. His steps grow pained, and he falls to the ground as a soundtrack transmits snippets of news from around the world: war, conflict, terrorism, torture (Oumzli’s headwrap and fall recall images from Abu Ghraib). Hope reappears in the form of music: Gaborit has returned, and his beat reawakens Oumzili to his higher, upstanding path. The light fades, the sound fades, but his steps continue.

The final part of the trilogy, La Terre en Transe (The World in Trance) is altogether more joyous and vital, its energies more extrovert. The chequerboard squares of light now reach out from the side wall across the ceiling, as if they had been thrown into the air. There are nine dancers, male and female, and three musicians; all mix and merge freely. As with HMADCHA, there are one-directional parries and retreats, like yearnings towards some higher plane, but the overall feel is far more multiform and multidirectional, with ragged circles, clusters, solo outbursts, headlong tumbles, sorties into and out of the wings. Sometimes the dancers change into shamanic figures in totemic masks, with fringes covering their faces, horns and feathers sprouting upwards. What keeps all these plural, centripetal energies together is the musical pulse, a kind of communal heartbeat. Again, the dancers exit in a kind of ecstatic ascension into the auditorium, until one shamanic figure is left to continue, beating out a rhythm and a chant.

Mystique, mystification

Following such a bold trilogy, Idée by Abdel Mounim Elallami – who has trained and danced with Ezzediou’s company Anania – suffers a little in comparison, though it does also show a younger choreographer exploring his voice and direction. Direction, indeed, is again a distinctive feature of this solo: as with Izzediou's trilogy, you sense the magnetism of a particular axis, as well as the reach, and failure to reach, the distance to which it points. There is, again, a move towards an earthlier realm of styles and symbols (a silver crown, his own upstage shadow) as that singular direction dissolves – yet in that process, this work loses somewhat more purpose than it builds. If Idée doesn’t always hold attention, it does hold promise.

Holding attention is a real problem for Mille et une Nuits, a performative installation by Iranian artist Sorour Darabi, currently based between Paris and Berlin. The event looks stunning – light pierces suspended blocks of ice, mists rise and billow, bodies emerge and disappear, contoured as silhouettes or manifesting as mythic beings – and it continues to look stunning for more than 2 hours. The audience is free to move around, though most stand or sit, and there is also a slow drip of people melting away towards the exit. Why do people leave shows? Usually, it’s either because they are bored or because they are offended. I don’t think it was offence, here.

The work is as miasmatic and wafting as the clouds, scenographic and sonic, that it drifts through. The performers wear cut-away clothing that part conceals, part reveals (buttocks especially). There are anemone swayings, opiate coilings, and occasional tendril-like couplings and throuplings as bodies meander about. Some moments are revelatory – an undulating copulation with an ice floe becomes a powerfully sensorial trance; a man flops and flails in meltwater like a newborn being – but these are a long time coming. The work’s title refers to the mythic stories of Shéhérazade, and Darabi’s programme notes suggest subversion of, identification with, and attraction to this feminine icon. The performance somewhat undoes the orientalist binaries of Shéhérazade’s story cycle, but it still feels in thrall to its own exotic erotics and misty-eyed mysticism. Moreover, where Shéhérazade seduced her audience with suspense and intrigue, Mille et Une Nuits – intentionally, perhaps, but not advantageously – is the very opposite of a page-turner.

Harmonies, discords – and sustainability

It takes quite a long time to get “into” Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione, a new, 90-minute work by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Radouan Mriziga, but – as often (if not always) the case with De Keersmaeker’s projects – the wait is increasingly rewarded as the work builds up its own world. As often with De Keersmaeker, music is far more than atmosphere and mood (as it had been in Mille et Une Nuits), and far more than accompaniment, foundation or score (as it is commonly treated) but becomes instead a creative and compositional partner for the choreography. The music is Vivaldi’s excessively well-known The Four Seasons, but it is not heard at all for a considerable time. Retrospectively, though, you begin to realise that it has been present all along, in the imagery immanent in the movement, first of a soloist (Boštjan Antončič), then of the three other men who join him (Nassim Baddag, Lav Crnčević, José Paulo dos Santos): you catch intimations of bird wings, of wind and weather, scattering and reaping, the spiral fall of leaves, the spokes and wheels of a world rotating on its axis. De Keersmaeker is usually less figurative in her musical correspondence, but the Vivaldi score, more than most of her others, is also full of pictorial figuration. The music is perhaps also implied in the rhythms flashed out by a back wall of fluorescent strip-lights that had signalled the start of the piece. It is there for sure in the dancers’ rhythms and phrasing, most obviously when two men start stamping out a long sequence which, eventually, you register as a step-for-note rendition of Vivaldi’s score.

After so many intimations and hints, when the music does finally burst in it feels tremendously satisfying: we have been primed for this moment of fulfilment and accord, and it carries us all the way through to the work’s end. Along the way, there are many pleasures to be had, each dancer a distinctively different presence, Crnčević standing out for his pinwheel spins, Baddag for his hip-hop pliancy (when the others turn upright, he turns upside-down). The texture of their action is held together by figure-of-eight walks – like a Möbius strip of steps, or an infinity sign repeated ad infinitum. Yet however circular time may feel, it is in the end sequential, and consequential: Il Cimento overshoots a full year’s cycle of seasons, moving into a second autumn and, as the work ends, towards a second winter. This is not a circle of renewal but a loop towards a destiny indicated by the music quietening and the strip-lights flickering out, and a recited text (by poet Asmaa Jama) that evokes our tipped-over, out-of-kilter ecological world.

I have long been a follower and admirer of the works of De Keersmaeker and her company Rosas, and Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione, co-choreographed with Moroccan-born PARTS graduate Radouan Mriziga, deserves admiration too, in my opinion: it is a great piece. It also brought up the long-standing question of the distinction, and connection, between artist and artwork, and the culture of the arts sector. On the opening day of Montpellier Danse, Belgium’s De Standaard newspaper broke a story about toxic work environments and professional malpractice at De Keersmaeker’s prestigious company Rosas, with De Keersmaeker singled out at its centre. What would be an appropriate response from the company directors? From company members (current or former)? From the festival? From a reviewer? Me? Never mind art, this was back to politics: the decisions, manoeuvres and communications made by people in different positions with competing interests.

If you have read this far, you already know that I decided both to review the onstage performance (from first-hand experience), and to raise the issue of backstage working practices (from second-hand reading). I hope to connect but not to elide the art with the politics of its production, so that both may be present. What will develop from the Rosas situation remains to be seen, but is it naive of me to hope that into the drama of politics (all character, action, conflict, and consequence) the spirit of music might enter? So that the energies that animate us might find some accord with the patterns that connect us. Perhaps that might incline our politics away from degeneration, towards regeneration. In any case, that is how I came away from Montpellier: with a wish for a world with less drama, and more music.

Written from the Montpellier Festival, France, 27 June to 1 July 2024.