A weighty state of weightlessness: Vizváry's melancholic mime floats through space with effortless ease in every movement, gesture and grimace

Loneliness, fear and moon dust. Prague's Švandovo Theatre hosted the internationally acclaimed mime and choreographer Radim Vizváry for the umpteenth time. In his solo performance Mime on the Moon, he tells with the boyish wonder and detachment of an old man the bittersweet story of a man lost at his core, who in pursuit of true emotion (and perhaps the meaning of life) sets out to explore the lunar landscape, and the landscape of the heart. Cut off from both people and life "down there," Vizváry's melancholy hero discovers the characteristic terra incognita not only around him, but above all within himself.

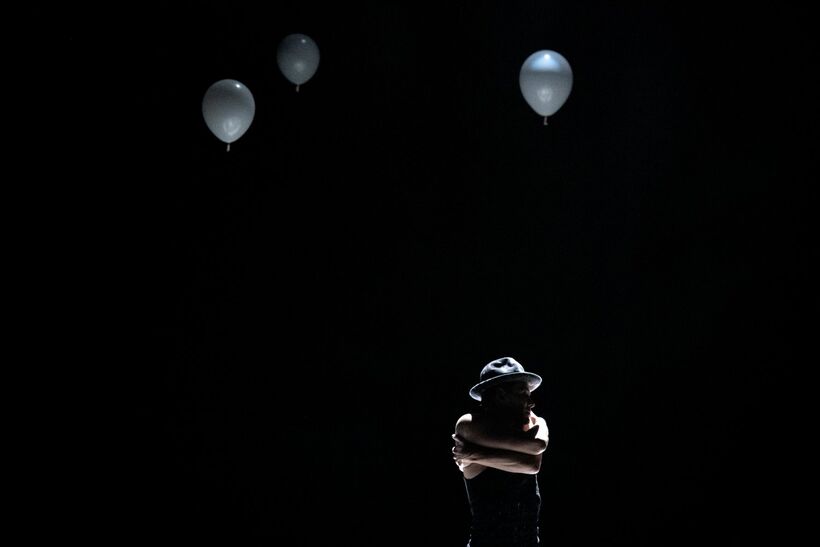

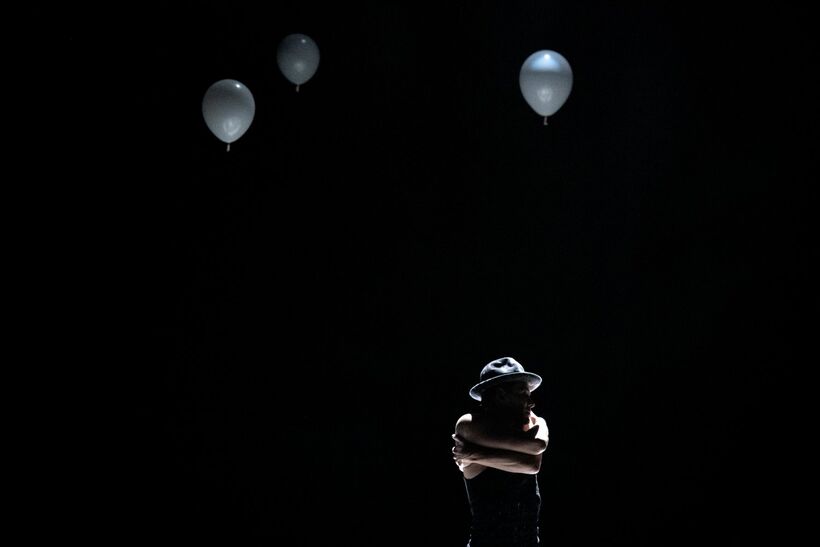

Mime on the Moon. Photo: Anna Šolcová.

Connecting the state of "weightlessness" with the existential heaviness inside is not only incredibly clever, but above all deeply human. The story of a man who falls victim to his own imagination is neither overly fatalistic nor depressing. Compared to Boris Hybner's cynical, shabby clown "loser", Vizváry's Mim on the Moon is alternately nostalgic and quirky. In his black worn coat, long-sleeved shirt and formal trousers, he looks like a character cut out of a black-and-white film grotesque. His nonchalant melancholy is more reminiscent of Buster Keaton than Charlie Chaplin. As in his previous one-man show Solo, Vizváry applies his roots in puppetry. He is a master puppeteer, but his animated instrument is himself instead of a wooden puppet. Especially in the opening part of the performance, his limbs and his whole body move as if they were attached to invisible wires. Every movement and gesture has that typically languid, seemingly clumsy thrill, but not for a moment does his performance lose its spark of life. He is so technically bravura, yet natural and spontaneous on stage.

The latest work of this exceptionally gifted performer could be a relatively "classic", technically polished pantomime show full of rewarding tricks and more or less surprising twists, if it weren't for the omnipresent dark undertones and unorthodox, grotesque scenes. It's the sting of tragedy that makes the show a unique experience that sort of defies any clear-cut genre classification. In terms of style, Vizváry here returns to "pure" pantomime as most audiences would imagine it (which is mostly humorous nonverbal theatre, usually featuring a performer with a white face and expressive muscular facial expressions). Vizváry's physical expression in Mime on the Moon, however, is closer to expressive dance and mimetic realistic theatrical expression than it might at first appear.

The proof is how convincingly he slides from comedy to tragedy, from smiling sneers to gloomy, more serious positions. It's not so much about the precise, choreographed absolute control over the body even in the smallest details, but about the very meaning of the individual movements with which the performer communicates. His combinatorial ability to combine very concrete depictions of imaginary objects with purely abstract movements that are rooted in authentic, often destructive emotions is truly unique. The traditional white mask of the mime has its role to play, but Vizváry himself has already demonstrated in the past, through his philosophy and his view of the art of mime as a form of non-verbal theatre, that he has outgrown all categorisations and definitions as a master of his craft and an artist in his own right.

Vizváry's original directorial-dramaturgical vision, which he unfolds in Mime on the Moon in a simple but solid narrative arc, lies in the art of suggestion. It seems like a paradox at first glance, and it's true that most of the individual sketches depend directly on situational comedy, physical gags and a certain literalness. Predictable games with gravity have their place here, of course. But unlike many contemporary performers, Vizváry is not afraid to venture in his micro-stories into places not everyone dares - the realm of abstraction and self-irony. Especially in the middle section, devoted to the actual stay on the moon, when the mobile phone, the slingshot, the heart, and finally the brain gradually disappear from the mime's hands into the void, one cannot help but recall the strange adventures of Baron Scarecrow. The idea that art doesn't have to make sense to make an impression is perfected by Vizváry the director. The sometimes frighteningly phantasmagoric outcome of initially innocent scenes is his signature: a deflated balloon becomes a deflated head sticking out of a uniform-like coat, an umbrella is transformed into a satellite receiver, a mirror instead of a face reflects interlocked fingers on hands so that they look like moving mouths. Mime's hands speak. In Radim Vizváry's dreamland, nothing is as it seems.

One of the many examples is the scene with the lone sunflower in a vase - an indifferent Colombine in heat to Vizvari's love-struck Pierot for the 21st century, who woos his prospective sweetheart in every possible way. Among other things, it is in this section that the performer's sense of comic timing comes into full play. Fittingly, it is also the only scene in which a human voice is heard, albeit in a deliberately goofy drawl reminiscent of Mr Bean's gibberish. The only contact Vizváry's tragicomic character makes is with a mute flower. With the naive determination of the Little Prince - and the seductively confident mannerisms of Casanova - he eventually wins her for himself. The biggest joke, though, is that after he confesses his heart's motives to her to the beat of a pop love song with a hint of awkwardness, all romance ends and in a fit of desperation and rage he rips her to pieces with his hands and teeth - literally eating her up with love itself.

Another clever choice is the consistent black and white aesthetic itself, which anchors the roughly hour-long performance in a pleasant limbo without space and time. With absolutely minimal visual distractions, Vizváry can manipulate both as he needs to. The play of light and shadow creates truly compelling images in non-violent tones of colour. For example, the opening scene, when Vizváry as a lone man embarks on a pilgrimage through the rainy streets, contrasts impressively with the warm, sepia tones of the following sequence in an inhospitable landscape bathed in cold moonlight. Karel Šimek's light design and Ivo Sedláček's soundscape complete the illusion of space and time with a minimum of resources. The lunar surface otherwise evokes only a circle of light in which the performer moves, especially in the middle part. Everything else is enveloped by darkness and black cloth, from under which silhouettes of larger and smaller practitioners emerge. Except for the mime's face, glowing out of the darkness, with its distinctive white make-up, everything is surrounded by cosmic nothingness. That's all the director, dramaturg and performer in one person need. A shining example that less is more.

The basic principle of clowning is that the clown is introduced to any "discovery" (whether it is an object, circumstance, idea, or emotion) at the same moment as the spectator, in real time. While Vizváry's Mim does not improvise, the magic of sharing the present moment still carries through the air. His storytelling talent is evident, among other things, in the fact that the vast majority of the scenes in this series of loosely connected panoramas would stand equally well on their own. He is able to connect with his audience like few contemporary performers and his ability to move the viewer's heart is unparalleled in our country. One can only hope that in the future he will not stay only on the boards of the Švand Theatre. And that Vizváry's undeniable genius will soon reappear in any form.

Written from the performance on 19 February 2025, Švandovo divadlo, Prague.

Mime on the Moon

Written, directed, acted by Radim Vizváry

Directed by Trygve Wakenshaw

Design: David Janošek

Light design: Karel Šimek

Sound design: Ivo Sedláček

Dramaturgy collaboration: Hana Strejčková

Production. Ilona Strejková