The initial impetus for the ballet Scheherazade in 1910 was a colourful symphonic suite inspired by Tales of the Thousand and One Nights, which Rimsky-Korsakov had composed in 1888. Captivated by its beauty, Sergei Diaghilev, as an innovative impresario, chose it for his second Paris season. He commissioned the choreography to Michael Fokine and the set design to Léon Bakst. It was not their intention to translate the narrative-based Tales of a Thousand and One Nights into dance form, as the creators chose only the first "fairy tale" dealing with the betrayal of the king's wives and their punishment. The result was a production that has gone down in history for its innovative choreography, somewhat provocative subject matter (the harem orgies and murders of the king's wives and slaves were depicted on stage), sumptuous and very colourful orientalist sets and costumes, and of course the dance performances of the performers led by Ida Rubinstein and Václav Nijinsky. Scheherazade became one of the most famous and most performed productions of Diaghilev's company and its follow-up groups and was performed all over the world. It has also appeared several times on the stage of Prague theatres, most recently at the National Theatre in 1974, choreographed by Jiří Němeček Sr.

Mauro Bigonzetti's new Scheherazade has little in common with the Diaghilev one, but here too the music was the main inspiration. However, Rimsky-Korsakov's iconic symphonic suite was joined by a Sinfonietta on Russian themes, and the resulting ballet is twenty minutes instead of the original forty. The choreographer takes the theme of the well-known story and focuses in particular on its two main characters: the betrayed, vengeful and brutal King Shahriyar, who decides to take a new consort as his wife every day, and kills her after the first night spent; and Scheherazade, the vizier's daughter, who offers herself to him and leads him to transformation through her wit and inner strength. The main characters here represent the generally masculine and feminine principles and the gradual search for balance, which is reflected in the dramatic structure of the play.

Bigonzetti's Scheherazade does not tell fairy tales. The ballet speaks to the ever-present theme of violence against women

First, the women's chorus is introduced as a feminine principle, with the dancers gradually appearing on stage between orange scarves and dancing to the strains of Korsakov's Sinfonietta. The light and flowing melody of the allegretto evokes a more or less carefree atmosphere that suggests no threat. The oriental locale is so far suggested only by the costumes styled according to the European ballet tradition (sheer striped trousers, crop tops, veils). Bigonzetti then expresses the given colouring with lingering movements, undulating hips and ornamental hand gestures, while we hear only faint oriental echoes in the music. The stereotypically presented feminine ethereality is underlined by the use of pointe shoes.

Although the groupings and formations of this women's exposé are quite variable and the movements of the dancers are beautiful to seductive, the often repeated combinations and poses, such as the stance with the leg resting on the toe, start to get a bit tiresome after the first ten minutes. The initial boredom is momentarily broken by the arrival of Scheherazade (Romina Contreras), whose head is adorned with a golden helmet with a bird motif symbolizing freedom. However, even her graceful ascent does not yet have enough dramatic potential, and so the viewer can only assume what the girls wanted to convey to each other. Only the manipulation of scarves and veils perhaps hints at their subordinate position and unfreedom in a patriarchal system, or even an impending existential threat.

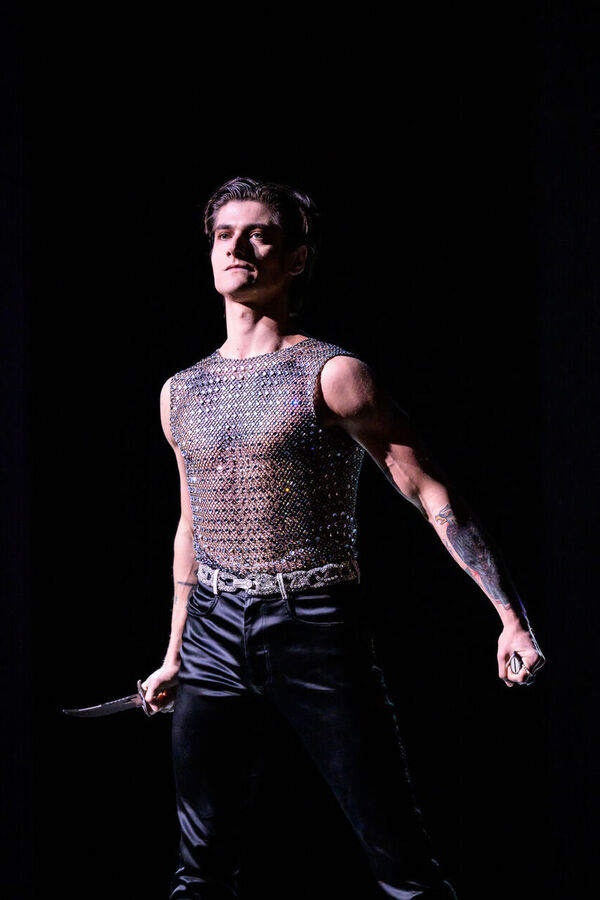

After almost half an hour, King Shahriyar arrives, bringing a completely different energy and his character is truly spectacular thanks to the original costume, spatial and musical design (however, I don't want to reveal more, so that the visitors of the reruns don't miss the moment of surprise). Paul Irmanov gives his role the gloom, tension, dislocation and at times the expression of a real psychopath. His male companions, in long dark coats and high fezzes, embody strength, aggression and toughness. The archetypal (or rather stereotypical) depiction of masculinity and femininity is reflected in both the movement vocabulary and spatial patterns. While the women undulate their hips, their dance often incorporating rounded shapes, and the chorus moves in an acesque path, teasing out subtlety to submissiveness, the men stamp out straight lines, actively place themselves in rows and diagonals. Their dance is brimming with power elements, stomps and leaps. In this interesting way, the choreographer contrasts the dynamic dance of the male chorus with the soft, drawn-out tones of the piece's wind instruments.

The striking presentation of the masculine principle culminates in the solo of the king, which reveals not only anger, but also a kind of inner pain that tears him apart and drives him to carry out his brutal plan. The ballet finally begins to gather momentum; the tension builds, captivates and never lets go. The strongest moment is the depiction of the king's cruelty towards his wives. The stage shorthand, without being overly descriptive with a few exceptions, effectively depicts his actions as a serial killer. The desperation and futile struggle of the poor women contrasts with the indifference of the courtiers who throw them into the king's arms; Irmanov's expression conveys not only brutality but also the pleasure of cruelty. I feel anxious and the stories of many women from long ago and in the present who have suffered and continue to suffer from male violence come to mind...

Seeing the havoc left behind by the king's massacre, Scheherazade decides to take action. She removes the helmet from her head, which apparently protected her from his actions, and cuts her hair, an act that in Persian tradition is a symbol of mourning but also of resistance. She voluntarily becomes the king's wife. The climax of the whole ballet is thus the scene of their confrontation, one big and long duet between Scheherazade and Shahriyar. During it, there is a fight, a negotiation, the king's epiphany, and Scheherazade's apparent victory, but the ending remains open to the viewer's own interpretation (did she kill him, or can he live on, improved?). For the first time in the entire work, there is a gender-blind movement articulation. Scheherazade comes across proud, strong and determined; her almost instantaneous sovereignty is somewhat less likely given the previous characterisation of the king, but clearly has an effect. Partner dancing and unison moments are given almost equal space; the main characters' interactions are often slow-paced, but there is an almost palpable tension in their movements. One must highlight the superb interplay between the two performers in this challenging duet, their technical perfectionism and the expressive depth with which they were able to draw the audience into the picture of a complicated relationship.

The fast pace, tension and action of the second half of the work compensates to some extent for the lengthy beginning. The question remains, however, whether the addition of the half-hour Sinfonietta was really necessary, as the ballet felt exactly half an hour longer than it needed to be. There are understandable rational reasons for this choice: when the theatre decided to present Scheherazade on its own, rather than in a composed evening as would have been suggested, the score had to be stretched. However, the opening half-hour harem divertissement does not strike me as the most dramaturgically happy or interesting solution. And since it was decided to go for a longer running time, it would have been appropriate to put intermission in the middle.

Mauro Bigonzetti presented himself to the Prague audience in a slightly different position than in 2019 with Kafka: The Trial. The emphasis on the expression of the main performers remains, but the contemporary original movement concept is replaced in Scheherazade by a less progressive, sleeker rendition, including a highly stereotypical gender differentiation of the dance vocabulary and oriental poses vaguely capturing Eastern esprit. The immersive set design of Kafka: The Trial, which brilliantly combined video projections with physical props, was this time replaced by primordial, mostly static images. Projections of the façade or the interior of an Ottoman-style palace are only occasionally supplemented by themes of flowing blood, rain or fire (when the protagonist enters into marriage with the king). But all this is offset by the great music, which was the primary inspiration for the ballet a hundred years ago and now. The National Theatre Orchestra, under the direction of Johannes Witt, interpreted Rimsky-Korsakov's challenging and varied score with a grace and mastery not always commonplace in ballet music. Likewise, the entire dance company gave fantastic performances without any signs of opening night jitters.

Written from the first premiere on 28 November 2024, the historic building of the National Theatre, Prague.

Scheherazade

Choreography: Mauro Bigonzetti

Music: Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov

Dramaturgy: Patrizia Dall'Argine

Lighting design and video projection: Carlo Cerri, OOOPStudio

Costumes: Anna Biagiotti

Assistant Choreographer: Roberto Zamorano

Ballet Master: Miho Ogimoto, Tereza Podařilová, Jiří Kodym

Musical direction: Johannes Witt