La Strada as a life journey through circus archetypes

Federico Fellini's La Strada, a 1954 film, is undergoing a surprising renaissance in dance this year. Jiří Bubeníček is preparing his version for the Prague Chamber Ballet, and Alina Cojocaru has taken up the same theme in London, inviting Slovak choreographer Natalia Horečná and Bubeníček's brother Otto, who has signed on for set and costume design.

A legendary film

Alina Cojocaru, a former Principal Dancer of both major London companies The Royal Ballet and English National Ballet and a regular guest of John Neumeier's Hamburg Ballet, has taken an interest in the story of the girl Gelsomina several years ago. At that time, she worked with Neumeier on his new production Liliom, where she played the female lead, and the choreographer recommended the performers to look at La Strada by the famous Italian director Federico Fellini as part of their preparation. The idea for a dance work has been in Cojocaru's mind for a long time, finally materializing in her first full-length production, which is backed by her production company Acworkroom, founded by the dancer in 2019 to give her more creative and artistic freedom. The international creative and artistic team was largely made up of artists who had at some point in their careers been through Hamburg Ballet, from Natalia Horečná and Otto Bubeníček to the six-member choir. They were joined by Cojocaru's longtime onstage and real-life partner Johan Kobborg and Mick Zeni, the former Principal Dancer at La Scala in Milan, playing the leading male parts.

The story of La Strada is not particularly complicated or tangled, but it is very dark and raises many uncomfortable questions. In order to support her four children, her mother sells the young Gelsomina to a wandering street artist, the boorish lout Zampanó. Childlike, naive, immature, perhaps even mentally retarded, Gelsomina makes her way through life and the Italian countryside with him, and while she learns various performing skills, Zampanó insults her, physically and mentally abuses her, and generally treats her like a piece of shit (sexual violence is also hinted at later on). This results in Gelsomina's attempt to flee, but the two soon meet in the city, where a circus is performing, and Zampanó wants to join it. We also meet acrobat and clown Il Matto, between whom and Zampanó the tension between is palpable from the start, probably coming from their shared history. And Il Matto feeds it with his constant pranks and mockery.

.jpg)

Gelsomina gingerly starts to blossom in her new surroundings, possibly finding her own self, something the possessive Zampanó fundamentally dislikes. It all leads to a fight, after which Gelsomina is offered a permanent position in the circus, but she decides to stay with Zampanó because "if I don't stay with him, who will?". Later, the pair meet Il Matto again, and in a fit of macho madness, Zampanó accidentally kills him. This critical event shatters both Gelsomina and Zampanó mentally and triggers a drastic transformation, which results in Zampanó leaving Gelsomina in the mountains at night. We jump forward in time at the end of the film. Zampanó searches for Gelsomina on the seashore from where he bought her, learns that she is dead, and Fellini leaves him in despair, alone and possibly remorseful, on the beach.

An innocently devoted female lead

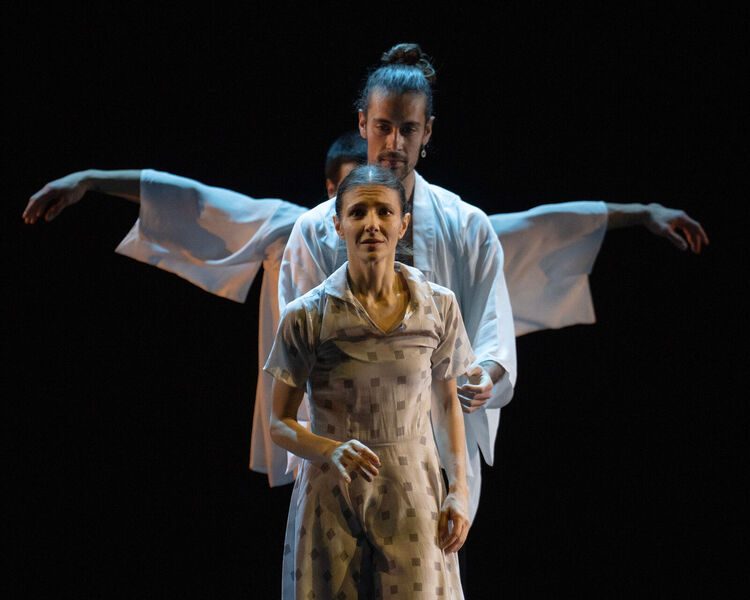

The libretto of the two-act ballet focuses its attention mostly on the central trio and Gelsomina's inner world, because it is her perspective through which we perceive the whole story. In composition, the narrative is framed by Zampanó haunted by a past materializing in visions of the dead female protagonist. She is portrayed by Alina Cojocaru as a perfectly pure, innocent soul. She yearns for the world, adventure and affection with an almost childlike sincerity and sparkling wide eyes. She makes no pretense in her feelings, and is achingly straightforward and direct in her emotions, inherently incapable of insincerity or calculated actions. On the one hand, the ability to perceive her surroundings, all situations and people always in a fundamentally positive way and with indestructible enthusiasm can be seen as her strength, but at the same time it inevitably becomes Gelsomina's own bane. Her kindness and goodness are such an integral part of her world that once they're so violently shaken to the core, the girl begins to lose herself.

.jpg)

In contrast to the film, the relationship between her and Zampanó is not built up over a long period of time. We see an initial fascination, an attempt to please and meet expectations she doesn't even understand herself, so her efforts are doomed to be a failure (and a cause to Zampanó's annoyance). The first genuinely pleasant encounter comes at the circus with Il Matto, who doesn't perform on a tightrope but rides a unicycle, juggles and performs small magic tricks. Initially, the duets between him and the enchanted Gelsomina are incredibly endearing, until the usurping Zampanó enters the picture and even Il Matto himself backs out after discovering how frighteningly devoted Gelsomina can be with her feelings. How all-encompassing and unconditional her affection is. What she is offering without even realizing it in her own immaturity. It is Il Matto's rejection that deals Gelsomina the first major blow. The world around her ceases to make sense. She doesn't comprehend it, doesn't understand. Like a little child desperate for acceptance and love that they never got.

Zampanó is rude to her and jealous of whatever positive attention she receives. Il Matto, a serial joker who takes neither anything nor anyone too seriously, is perhaps subconsciously protecting her by his decision, which however doesn't change the fact that Gelsomina can rightfully feel used by both men. Because the show must go on and the circus is not asking any questions.

In the second act, the already tender story line crumbles, becomes thinner and loses its contours. We enter deeper and deeper into Gelsomina's soul, whose twists and turns are accompanied by two metaphorical figures (Marc Jubete, David Rodriguez). At times they are comforting guardians, at times an inner voice, at times a conscience or a mirror reflection of key figures in Gelsomina's life. The edges between the real and unreal worlds blur into each other, and the situation moves freely from idealized dreams to a reality much closer to a nightmare. Similar to the film's premise, Il Matto's death is a crucial turning point. With it, Gelsomina loses her innocence and the breakdown of her psyche is reflected in the ultimate rupture of the chronological storytelling.

A blurred narrative

In the narrative it is no longer clear what is real and what is just an imagination, what has happened and what has not, who is alive and who is dead. The magic of the unsaid is enhanced by the circus setting with its typical characters of clowns and acrobats, where Gelsomina gradually becomes the miserable, tormented Pierrot. At the very end, the characters shed their costumes and masks. The illusion is over, Zampanó, plagued by his actions, has nowhere to hide and nowhere to run. And in her dreamy, idealized circus stands Gelsomina. But she's all alone...

In the dancing vocabulary, Natalia Horečná's La Strada does not reach for overly unexpected ways of expression. She works with a flowing and musical, yet surprisingly conventional and not very inventive mix of very loose neoclassical with contemporary dance elements. One cannot deny its clarity, however, the usage of certain gestures and signs, which at their core refer to the traditional ballet mime, does seem somewhat unnecessary.

From a dramaturgical point of view, the ballet begins to fall flat in the second half, when the choreographer's overuse of some staging methods and duplications of certain motifs muddies the already liquid narration. Time flows differently here than in the linear first act, thanks to the merging of the worlds, thus a cut here and there would only be to the benefit of the piece. In any case, Horečná is very good at handling stark contrasts. Some of the most powerful moments of her production are undoubtedly the ones of Gelsomina's dejection, deep introspection or gradual loss of contact with reality and with herself, accompanied by the most exuberant cabaret-like tones of gallops.

.jpg)

Otto Bubeníček's set and costume designs are modest and make do with comparatively little, yet they manage to communicate what is needed. The circus shines, it's full of colour (and creepy gargantuan clown marionettes), but it doesn't come across as overtly exuberant. The atmosphere is intimate and veiled from the beginning, the ambiguity is supported by the light design. The ever-present curtain, which serves as a divider between the backstage and the manege, but also between different realms, also plays its part.

The musical collage (for which I have to appreciate its complete and meticulous listing in the programme) was compiled from Nino Rota's rich film composition work (music for Fellini's La Strada, Il Casanova or La Dolce Vita, including selected pieces from Luchino Visconti's Il gattopardo). Sadly, however, the cohesion of the final mix suffered from the necessity of using a recording (not a live orchestra) where the transitions were not always entirely seamless (and one could not always call it intentional).

The power of artistic charisma

If the production of La Strada had anything to rise and fall on, it was the interpretation. First and foremost that of Alina Cojocaru, who is an artist capable of portraying a banana peel and making you absolutely certain you are looking at a masterpiece in a world-class gallery. Her deep immersion into the role of Gelsomina didn't have a single weak spot, and it's hard to find words for the nuanced qualities she endowed her character with. The way she was able to progressively uncover the individual layers of her character, to outline their contours and to gradually paint them in the most subtle shades of emotions, is absolute and truly incomparable. She was the perfect guide through the story and one of its constants, always there to make sure you knew what was happening and what she was experiencing by a single glance and a quiver in her face. The inner deconstruction that Gelsomina underwent in the last third of the piece was both chilling and eerily fascinating, and the bittersweet melancholy that enveloped her at the very end was almost palpable.

.jpg)

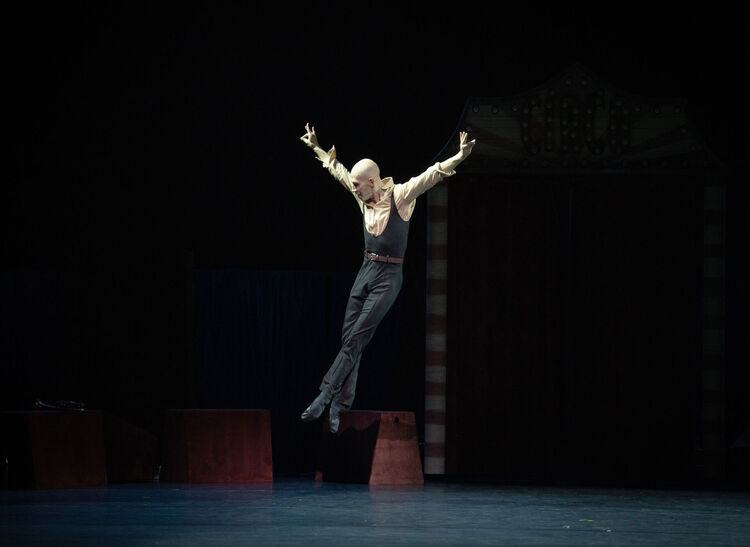

Il Matto of Johan Kobborg was a charming character with his shenanigans and mischievous levity; moreover, the deep artistic and human understanding between him and Cojocaru added an unsuspected magnitude to their shared scenes. Also worth mentioning are his uncannily brilliant variations full of little allegro jumps and sharp, impeccable feet. I do feel compelled to point out that Kobborg is fifty-one years old. Well, once a Bournonville school graduate, always a Bournonville school graduate...

As Zampanó, Mick Zeni exactly matched Horečná's (and Cojocaru's) vision, displaying any emotion through fury and violence, but deep down very vulnerable and at his core fragile, much like Gelsomina. I admit that I personally wasn't too convinced by such an expressive (and above all recognized from the beginning) humbling of such a complex character. Even the film's Zampanó experiences a major transformation at the end of the picture, triggered by the murder of Il Matto and the events that follow. Yet for the vast majority of the story, we see him as a macho piece of shit, because there really is no other way to describe him.

Horečná doesn't devote much space to introduce Zampanó's character, she doesn't highlight his negative traits, in her vision he seems more like an emotionally immature boy who fights for attention by pulling pigtails. There are no black-and-white characters, of course, but in the case of Zampanó I find such a view to be a relativization of what is objectively wrong, which is also rather dangerous. On the other hand, it all makes sense if we consider that the choreographer sees the story through Gelsomina's eyes, whose capacity for both empathy and forgiveness is truly infinite. It is presented, not only here but across our culture, as universally the greatest (especially) female strength. I, however, can't shake the feeling that, especially in certain situations, the line between strength and stupidity is alarmingly thin...

.jpg)

La Strada by Natalia Horečná and Alina Cojocaru is an incredibly peculiar affair. Full of (not only) existential questions, ambiguities and contradictions. The storytelling and its pacing would probably have benefited from the involvement of an experienced dramaturg and director, who would have been able to elevate an already promising work. In the end, the production is thus raised above the average by exceptionally charismatic performers who capitalize on their many years of artistic experiences, proving incidentally that even in this particular segment of the dance world, an active performing career truly does not have to end at the age of forty. And maybe it even should not...

Written from the show on 28 January 2024, Sadler’s Wells, London.

La Strada

Choreography: Natálie Horečná

Music: Nino Rota

Set and costume designs: Otto Bubeníček

Light design: Andrea Giretti

The review was funded by the European Union thanks to the Czech Recovery Plan and the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic.