Like Water for Chocolate – Mexican soap opera in ballet

The Royal Ballet prides itself on regularly producing new, original works. It has both a resident choreographer, Wayne McGregor, and an artist in residence, Christopher Wheeldon. And it is the latter who is responsible for continuing the tradition of narrative ballets that he creates for the UK's leading company. The very last was his version of Laura Esquivel's Mexican novel Like Water for Chocolate in June 2022, which was presented in cinemas around the world during January/February 2023.

Christopher Wheeldon is one of the most acclaimed ballet storytellers of the early 21st century. He has staged extremely successful productions of Alice in Wonderland (The Royal Ballet, 2011) and Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale (The Royal Ballet, 2014), as well as his own version of Cinderella (Het Nationale Ballet, 2012). Alongside this, he is a proficient choreographer of musical theatre on the West End and Broadway, with one of his most successful productions being An American in Paris (2014) performed from Paris and London to New York, Japan and Australia. His prerogative is both his ability to tell a story with lightness, wit and fresh dance vocabulary, but still traditional and accessible enough for more conservative audiences without the results seeming dated or dysfunctional in today's world.

In addition, he knows how to surround himself with a number of excellent and previously proven collaborators who help to form a piece of theatre that is in the best sense of the word perfectly crafted and fulfilled. So, this time, too, Wheeldon has reached out to composer Joby Talbot, the author of music for both Alice and The Winter's Tale, who has been tasked with creating a score that captures the esprit of a sunny Mexican village, as well as Bob Crowley, a set designer whose sets are opulent and visually spectacular, but not cumbersome or stifling in their massiveness.

Talbot's composition is once again excellent, at times almost cinematic in its melodies (but not cheaply pandering), full of typical instrumental colours of Central and South America – the strings of guitars and harps and the winds of ocarinas, special attention is paid to the multiplied percussion part of the orchestra. The rhythmization refers to Latin American folklore, and the tempo and the desired atmosphere are firmly in the hands of the Mexican-born conductor Alondra de la Parra, who also served as Talbot's consultant.

In the first act, a huge canvas composed of typical lace motifs dominates Crowley’s set design. The local atmosphere is complemented by Lynette Mauro's costumes, which, along with the masks, make-up and head ornaments, are most striking in the "brides" standing or sitting in the background as uninvolved, silent observers.

In addition to this, Wheeldon can draw implicitly on the excellence of the dancers of The Royal Ballet, who, trained by the works of Ashton and MacMillan, are among the finest actors. Which in the case of Francesca Hayward, for whom the central female character of Tita has been created, applies not twice, but three times.

The final production of 1989 celebrated Mexican novel by Laura Esquivel, Like water for chocolate, set in the early 20th century and following its protagonists over the span of thirty long years, should therefore be a guaranteed success.

But it's not. And no matter which way I look at the work, the original novel seems always as the one to blame. Esquivel tells the story of a Mexican girl, Tita (Hayward), the youngest of three daughters of the widow Mama Elena (Laura Morera), who falls in love with a young man, Pedro (Marcelino Sambé), but whom she cannot marry, for as the youngest daughter she must remain single and at the disposal of her aging mother. So, Pedro ends up marrying Tita's sister Rosaura (Mayara Magri), with whom he gradually produces two children while being actively unfaithful to her with Tita. When Mama Elena discovers this affair, she immediately sends Pedro away with Rosaura and their young son Roberto, which causes the child’s death, and when the news reaches Tita, she confronts her mother in a flurry of grief, after which she suffers a complete mental breakdown and is taken to a sanatorium by a family friend, physician John Brown (Matthew Ball). Four years later, a healed Tita accepts John's marriage proposal along with the news that her mother has died. At Elena's funeral, the whole family is reunited – Tita with the doctor and his son Alex, Pedro with Rosaura and daughter Esperanza, and middle sister Gertrudis, who has fled her home in the arms of revolutionary Juan Alejandrez. Tita and Pedro fall again into their romance that has not been diminished by four years of separation, marriage, two children and an engagement. The amorous outburst awakens the terrifying ghost of Mama Elena, who haunts the desperate Tita and disappears only when the girl drives her away thanks to information from her mother's diary, which reveals secrets from the past. The young Elena was in love with a penniless young man (Joseph Sissens), but her parents forbade her to marry him, and during their attempt to elope, Elena's brothers stabbed her lover to death. However, before the horrific apparition of the dead mother disappears, vision of her ghost manages to nearly kill Pedro. The slowly recovering man is cared for by Dr. John, to whom, in a flash of morality, Tita has meanwhile returned the engagement ring, and while Pedro recovers, his unloved, cheated wife Rosaura descends into madness and manipulative mania, dying only a short time after she fiercely prevents her daughter from befriending the doctor's son. Twenty years later, Esperanza and Alex get to marry anyway, Tita and Pedro can finally be together and, to quote from the programme, "In the final act, their bodies ignite with passion as they cross the border of the mortal realm."

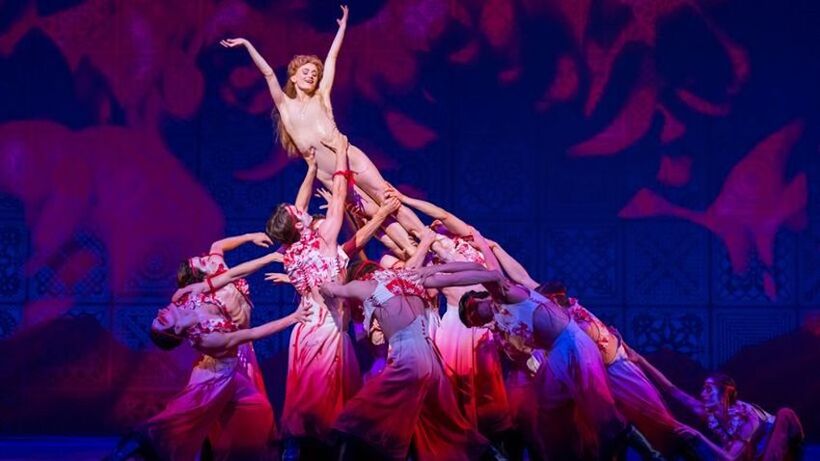

Add to this the story introduces (in exactly two places) Tita's magical ability to channel her emotions into the food she cooks – so her unhappiness and heartbreak-filled wedding cake for Rosaura and Pedro poisons the wedding guests, who in Wheeldon's production expressively vomit into the orchestra pit... Conversely, the dinner prepared on rose petals from Pedro sexually inflames Gertrudis so much that she throws herself into the arms of the passing Juan Alejandrez in an ecstatic haze, and together, accompanied by suggestive movements, they gallop away.

Frankly, there are many quite logical questions. However, I am not convinced that I can hold accountable a work that I am unable to describe as anything other than a Latin American soap opera, even if I tried. Perhaps I'm doing the literary template an injustice, perhaps the unconvincing result is much less its fault and more the fault of Wheeldon's script and chosen dramaturgy. Be that as it may, the ballet is strangely overcomposed, the pacing unbalanced – in the first act, twists and turns are thrown at the viewer with the cadence of an uncalibrated machine gun, so that the last act is really just a bite-sized flip and the final abstract duet, which in the context of a by-then almost anxiously realistic work full of period costumes, kneading dough and stethoscopes seems extremely odd to say the least. Then even objectively great passages, moments or individual performances either get lost or simply aren't able to balance out the blandness of the rest. And of the final image of the bed on fire...

Wheeldon has clearly demonstrated that he can create vividly danced, dynamic, energetic ensemble scenes - which is certainly no small feat, especially in the context of contemporary choreography. On the one hand, he skillfully plays with small, meaningful details, on the other hand, he suddenly unwinds the plot with descriptive shifts on the level of the most poorly rendered ballet pantomime.

For the first time, the solo variations and duets gave me a feeling of a kind of schoolboy mushiness and formal and structural cliché, although they offered a few flashes of something new. What suffered most, however, was Wheeldon's talent for narrative, definitely lost in the twists and turns of a story that tries to be realistic and physically tangible as well as dreamily ephemeral at the same time, and unlike the most famous titles of ballet romanticism, these contrasts simply doesn't work here.

Like Water for Chocolate

Choreography: Christopher Wheeldon

Script: Christopher Wheeldon, Joby Talbot

Original novel: Laura Esquivel

Music: Joby Talbot

Set design: Bob Crowley

Costumes: Lynette Mauro