Madrid en Danza Festival – Contemporary Issues and a Safe Bet

Every year, the month of May in Madrid is marked by the city’s largest festival, Madrid en Danza. Under the direction of Blanca Li, this year saw the 39th edition, featuring over twenty productions across various locations in the Madrid region. This edition’s program was notably highlighted by three international names that automatically became the focal point of audience interest: Age of Content by (LA)HORDE performed by the Ballet National de Marseille, UniVerse: A Dark Crystal Odyssey by Wayne McGregor’s company, and EXIT ABOVE – after the tempest by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and her company Rosas.

Let’s dance for a while, the heaven can wait…

Since 2019, the Ballet National de Marseille has been led by the collective (LA)HORDE, consisting of Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer, and Arthur Harel. In their production Age of Content, they focus on the relationship between humans and social media, exploring the physical and emotional reactions influenced by this extended reality. The opening scene features a remote-control car, reminiscent of the toy many children played with if their parents could afford it. The one on the stage of Teatros del Canal, however, was life-sized, a large steel structure with typically rounded curves, a front bumper, headlights, and a rear trunk. It resembles a vehicle on steroids, with a dose out of the designer’s control. The designer stands on a raised platform, initially guiding the machine's cautious movements.

Suddenly, a dancer emerges, jumping over the front hood to the roof, where she stands with arms outstretched. Her expression is unreadable, her face covered by a fabric that conceals her identity, yet her body exudes determination. Dressed in a light green, glittery set with a hood over her head, she interacts with the car, which starts to resist: at one point, it pins the dancer against the wall, and at another, it throws her off by a sudden lift of a hood side. As more similarly dressed dancers join in, the car bounces under their weight, reluctantly becoming a space for the ensuing battle.

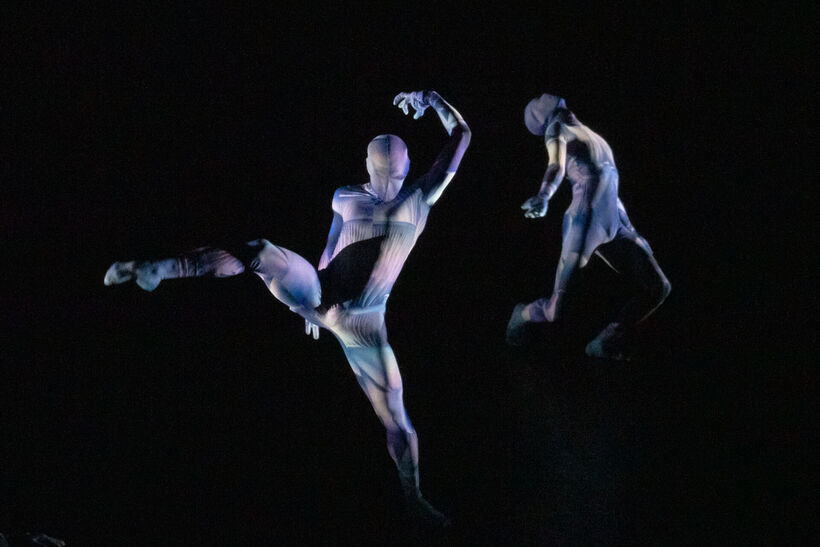

The dancers, indistinguishable from one another, engage in a staged struggle, exchanging punches, kicking, or throwing themselves to the ground. At a certain point, the previously calm music (initially just the sound of rain) shifts to pure techno, to which they simulate machine-gun fire in unisono – a power game for the best spot on the car roof. Yet something about the performers is peculiar. Faces covered by fabric prevent any emotional expression, and the hood obscures closer identification. The gender can be guessed only by body type and long black hair peeking from under the hood. It feels like copies of one single character, with each version losing a bit of initial vitality and humanity of the original.

They embody multiplicity, facelessness, inhuman ferocity, resembling a virus spreading dangerously over everything in its path. It reminded me of a Trojan horse computer virus, which, once it infiltrates your system, you lose everything in a second, at least the digital part. Virtuality or reality, both worlds seem equally transient and can vanish in an instant.

Some sequences take on a more dance-like character – moments when the group suddenly forms a specific pose, only to dissolve again in space and time. The dancers often form elongated shapes, connecting to create a living, functional organism across the formation. A similar approach is used by Canadian choreographer Crystal Pite, though her positions are much more statuesque; the (LA)HORDE mass is in constant motion.

In the final moments of the first part, everything escalates: to the rhythm of harsh techno, the dancers fire around them, partners brace against each other, with one partner’s legs representing gun barrels for the other to shoot. At other times, they throw their arms above their heads in regular beats, until eventually, all, including the car, gradually disappear from the stage. Without a clear winner, maybe all won, as ultimately, they are just extended “selves” of the original character, and this fray simply vanishes, ceases to exist, and its being fades away.

The second part creates a certain counterpoint to the first. If the first featured viral plagiarisms instead of human beings, the second overflows with accentuated individuality. Distinctive t-shirt with Heineken logo, girlish pigtail and miniskirt, jean secured halfway down the buttocks with the upper part of the butt exposed, dark t-shirt with embroidered six-packs... It is precisely Salomé Poloudenny's costume design that emphasizes the uniqueness and distinctiveness of everyone on stage. Conversely, an almost robotic walk with slightly bent knees, a pelvis tilted forward accentuating the lumbar curve, and arms slightly bent supports a certain mechanicalness. Overall, they form a peculiar squad of beings. Their movements and dances incorporate elements of violence, control, and submissiveness, erotic and sexual allusions, all shrouded in a depressive tone of musical, scenographic, and lighting accompaniment. The entire choreography maintains a peculiar, variable dynamic that doesn’t let you shift your attention elsewhere for a moment.

The finale of Age of Content brings something entirely different again. Cold lights give way to warm hues, the generics and artificiality of expressions and movements are replaced by eccentric smiles, and the choreographic structure permeates elements of almost all possible styles you can think of. The overall energy once again emphasizes the eccentricity of the previous part, though it’s obviously a false joy, perhaps influenced by antidepressants, it all feels like a bizarre dream that you know can’t be real, but you still doubt it for the first few seconds after waking.

(LA)HORDE does not tell a linear story nor attempt a simple and obvious retelling of various impacts of social media on our lives. It goes much deeper, capturing our thoughts, feelings, and emotions, transforming them into an apocalyptic image that shows the creators’ perspective on the subject. It’s a unique and effective approach, which was proven by the enthusiastic applause from the audience on the first night of its presentation.

It’s okay, next generation will pay the price

The second highlight of the Madrid festival was UniVerse: A Dark Crystal Odyssey by British choreographer Wayne McGregor. The piece, which has been in the company’s repertoire for only a year (premiering on May 13, 2023), is inspired by the 1982 film The Dark Crystal by fantasy director Jim Henson. Like the previous piece, UniVerse matches the relevance of its theme, as McGregor’s work addresses the ecological crisis of our Earth through an allegory of a world millions of light years away, using an energetic, typically McGregor dance vocabulary and modern technology. This piece was reviewed by Zuzana Rafajová (review here), with whom I fully agree in her judgments. The British choreographer’s work contains a lot of potential, which remains untapped and covered by additional layers of dance sequences. And although the performers deliver exceptional performances, their mastery reaches an imaginary peak, the audience's attention gradually dissolves in the multiplicity, generality, and generics of the author’s choreography. This was reflected in the relatively lukewarm reception from the audience; while Age of Content earned prolonged standing ovations, UniVerse ended with the third bow of the performers.

My walking is my dancing

The star choreographic trio concluded with Belgian choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and her company Rosas with the choreography EXIT ABOVE – after the tempest from 2023. Among the personalities involved in the creation of this production are Belgian singer-songwriter Meskerem Mees, blues guitarist Carlos Garbin, and musician Jean-Marie Aerts. Mees and Garbin even appear on stage alongside the dancers, blending seamlessly with the performers’ actions through their compelling guitar play and husky blues voice, often physically engaging in individual scenes.

EXIT ABOVE – after the tempest does not belong among complex choreographic canvases; on the contrary, as the annotation of the work suggests, the choreographer metaphorically returns to the roots, searching for the basic building blocks of dance. Therefore, walking is a frequent element, permeating the thematic musical accompaniment and song lyrics. Walking in Keersmaeker’s rendition has countless variations – it is stopped, rhythmic, irregular, completely unrestrained, but also with relaxed hips, accented steps, elongated strides, pronounced arm movements, and more. All variations, however, occur almost silently and cautiously, gently, delicately, and sensitively, leaving no room for invasive, sharp, or intrusive dynamic movements.

It cannot be said that the dancers interact significantly on stage or use partners' elements. They rather coexist in the same space, and everything happens "by chance," though it is clear that this effortlessness and spontaneity of the choreographic structure results from the perfect harmony of all stage components. This is evident in the frequent meetings in time and space when several dancers start moving in a single variation together, later joined by others, only for the newly formed group to dissolve again shortly after; everything appears completely effortless and natural, as if nothing special is happening. The dancers often spin, whirl through the space, never jumping high along the vertical axis, instead making low skips with soft and gentle landings. The curves of their bodies seem not to know any angular edges, everything arches in curves and roundness, the sharp edges of elbows and knees softened by gentle execution.

The creative team brings the simple structural form and the symbiosis between stage action, singing, and guitar accompaniment to absolute perfection. This is not a linear storytelling, which is characteristic of all three mentioned works. Even the titular storm appears only at the (no less impressive) beginning of EXIT ABOVE – after the tempest. In it, a huge piece of light plastic hovers just above the stage in gusts of wind. Before it even touches the stage, the wind from a large fan at the back blows it back up. Underneath is a lone dancer, seemingly tossed about in the stormy weather. Rotations around the axis seem to possess his body, and he always does something unexpected, such as jumping and landing hard on the upper part of his back. He doesn't hurt himself; he has complete control over his body and seems like the pliable plastic that flutters above him.

EXIT ABOVE – after the tempest is not a choreography that will leave you feeling exhilarated after watching it. Not at all. But you will leave feeling deeply touched. The detailed choreography of the work touches much deeper strings than mere affect. Keersmaeker rightfully belongs among the most prominent creators of our time, and this recent piece of hers is proof of that.

Written from the Madrid en Danza festival, May 9–26, 2024, Teatros del Canal, Madrid, Spain.

Age of Content

Artistic concept and direction: (LA)HORDE — Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer, Arthur Harel

Choreography: (LA)HORDE in collaboration with the dancers and ballet masters of the Ballet National de Marseille

Choreographic collaboration: Valentina Pace, Jacquelyn Elder, Angel Martinez Hernandez, Julien Monty

Stage design: Julien Peissel

Music: Pierre Avia, Gabber Eleganza, Philip Glass

Lighting design: Eric Wurtz

Costumes: Salomé Poloudenny

UniVerse: A Dark Crystal Odyssey

Choreography and direction: Wayne McGregor

Dramaturgy: Uzma Hameed

Music: Joel Cadbury

Video: Ravi Deepres

Lighting design: Lucy Carter

Costumes and masks: Philip Delamore and Dr. Alex Box

Word: Isaiah Hull

World premiere: May 13, 2023

EXIT ABOVE – after the tempest

Choreography: Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker

Choreography and performance: Abigail Aleksander, Jean Pierre Buré, Lav Crnčević, José Paulo dos Santos, Rafa Galdino, Carlos Garbin, Nina Godderis, Solal Mariotte, Meskerem Mees, Mariana Miranda, Ariadna Navarrete Valverde, Cintia Sebők, Jacob Storer, Pierre Bastin, Robson Ledesma, Margarida Marques Ramalhete

Music: Meskerem Mees, Jean-Marie Aerts, Carlos Garbin

Scenography: Michel François

Lighting design: Max Adams

Costumes: Aouatif Boulaich

Texts, song lyrics: Meskerem Mees, Wannes Gyselinck

Dramaturgy: Wannes Gyselinck

World premiere: May 31, 2023