No Time to Dance: Exhibiting the Multilayered Artwork of Noa Eshkol

When a dance artist can no longer create physical movement, one option is to start again by sewing fabric. The Noa Eshkol. No Time to Dance exhibition at the Georg Kolbe Museum in Berlin offered important insights into what creation can be.

Since the 1950s, Israeli choreographer and dancer Noa Eshkol (1924, Kibbutz Degania B, League of Nations Mandate for Palestine - 2007, Holon, Israel), for whom this year marks 100 years since her birth, has been a multifaceted figure. Today, she would be described as ‘multidisciplinary’, as in addition to her dance and movement research, she also developed a system of movement notation and engaged in textile art.

It is no coincidence that her retrospective was curated by the Kolbe museum (1928). The functional Bauhaus-inspired complex located in sculptor Georg Kolbe’s home and studio (1877-1947), has been key in preserving and mediating his artistic legacy since 1950. A unique space, both in terms of history and structure, for which modern dance and modernist architecture are important themes. In fact, a complementary presentation of its collection offers an insight into dance in the Weimar Republic.

The ground floor of the museum is dominated by a large room with huge windows that make the surrounding sculpture garden clearly visible, almost as if one were outside, along with two other with two other adjacent smaller rooms. Below them lies another floor, also dedicated to the exhibition.

Tracing Noa Eshkol’s Journey

Eshkol's history, still relatively unknown in the Europe-centric West, is intertwined with that of German Ausdrucktanz and, albeit not directly, with Kolbe. During the 1940s, Eshkol took lessons from dancer Tile Rössler, who introduced her to Labanotation. Rössler was part of the management of Gret Palucca’s school, before being dismissed in April 1933 due to her Jewish origins and emigrating to Palestine to found her own school. Earlier, in 1926, Kolbe made a portrait of Palucca dancing.

On Rössler’s encouragement, Eshkol then went to the UK where she first trained with Laban, before moving to the Sigurd Leeder School of Modern Dance. After returning to Israel at the end of the 1948 war in Palestine, she devoted herself to intense experimental teaching. With her ensemble Chamber Dance Group, she engaged in dialogue with pioneers such as Anna Halprin and Moshe Feldenkrais, which also features in the valuable letters displayed in the exhibition.

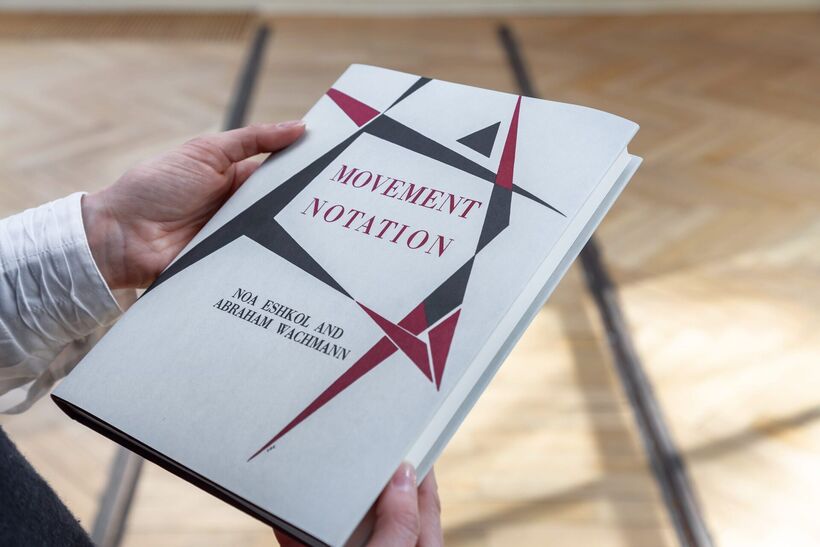

From the early 1950s onwards, Eshkol produced choreographic works and codified the Eshkol-Wachmann Movement Notation (EWMN) system with architect Abrahm Wachmann.

When Shmuel Zaidel, a member of her ensemble, was called to the front upon the outbreak of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, she stopped creating dances. She noted “this is no time to dance, we should wait until the war is over”. She then started to create colourful fabric wall carpets, sewed collaboratively with her dancers. According to Mooky Dagan, Chairman of the Noa Eshkol Foundation for Movement Notation, there were few rules in their creative process. First, they were usually assembled from collected or donated cloth, never cut or torn, and without human or animal likenesses. Then, similar to her movement approach, she would only use what was available: the material would create the composition.

Choreographing the Fabric, Modelling the Movement

The museum’s entrance and main hall are mostly dedicated to wall carpets. The first one is Palestinian Vase in a Window (1999), created on a traditional Arabian red keffiyeh (or “gutra”), a fabric mainly used by Palestinian farmers to protect themselves from the sun. As we know, the black/white keffiyeh has become a symbol of Palestinian resistance.

Some of the carpets evoke Japanese landscapes, positioned horizontally and stretched out like paintings to be admired face down, like water mirrors. Others depict the four seasons. Despite the fact that Eshkol maintained that there was no direct link between her choreographic and textile work, we might speak of a “choreography of fabric”. Thanks to the intersection of colours and their chromatic contrast, her textile production leaves a sensation that is both motoric and reflective. A motion inscribed in the time of waiting while sewing.

Apart from the carpets, the first few also rooms display paper drawings of Model of Orbit in the System of Reference (1975) by Eshkol and Amos Hetz, used to analyse movement possibilities within the EWMN framework, and its steel model, as well as photographs by Sharon Lockhart (2011). Furthermore, we can see John C. Harries’ preparatory drawing for Eshkol-Wachmann's draft of Movement Notation (1955). A series of EWNM explanatory plates (1950s) by Harries himself, with types of movement, such as rotating through 180 degrees, are exhibited in the underground room.

Thanks to the massive collection of writings, photos, drawings, and videos presented, the audience can understand the essence of Eshkol’ dance: a pure art form, to be practised without sets, or music, and minimal costumes (often just black shorts and tops). Here, human body parts are considered separate instruments, each with their own movement rules, like musical instruments in an orchestra. Original photos from the 1950s and some others from the 2023 reconstruction at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art (Berlin), with the Noa Eshkol Chamber Dance Group, show the contemporary nature of her choreographic signature.

An accompanying series of reference texts, such as 50 Lessons by Feldenkrais, as well as Eshkol and Wachmann's text on movement notation, help to deepen the bigger picture.

Video contributions by Omer Krieger and Yael Bartana and the commissioned work Forms of Breath (2024) by contemporary artist Ayumi Paul further enrich the exhibition: twelve stools made from a single piece of pear wood suggesting breathing exercises. Visitors are invited to move them around to practise. A reprint of the first version of Eshkol-Wachmann Movement Notation, produced in collaboration with KW, as well as a series of different seminar activities and performances, expand on Eshkol’s work.

An Exhibition as a Place to Reflect

In curator Kathleen Reinhardt’s note, preparations for the exhibition took place “at a time marked by the harrowing events of 7 October 2023, one day after the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, and the terrible war in Gaza”. It goes on to quote an excerpt from Eshkol’s introduction to Debka: Arab and Israeli Folk Dance (1974): “This book is dedicated to the hope that fruitful interaction between cultures can be achieved, and to the belief that in fact the two peoples can live peacefully together without either losing its individuality.”

Reinhardt continues, “This exhibition is also intended to be a place to pause and reflect on hope in a time that is characterised by pain, sorrow, and hopelessness.” Words that, far from being pure rhetoric, demand to resonate louder in the present climate, in the name of the wars going on, from the most well-known to the most silenced.

A visit to the Kolbe Museum produces an inner upheaval that goes far beyond reflections on artistic research, embracing, perhaps without direct intention, inescapable social themes linked to a reality in dangerous free fall.

Furthermore, the exhibition structure is a valuable example of how choreography is a territory, generating multiple research layers. Embracing different kinds of involvement, it provokes true experiences by establishing bridges with the recent past, not only deepening the historical and didactic knowledge of Eshkol’s body of work, but also succeeding in moving beyond visual perception.

Written from Noa Eshkol No Time to Dance, with Yael Bartana, Omer Krieger, Sharon Lockhart and Ayumi Paul, 15 March to 25 August 2024, at the Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin