Otto and Jiří Bubeníček again in Prague, four years on

The names of the Bubeníček twins have become a distinguished and reputable brand not only in the world of dance. Their performances are also attended by those who do not regularly savour dance. They feel they simply have to see the Bubeníčeks, since the brothers’ lustre is comparable to that of some celebrated opera divas. Since their first – and fateful – engagement at John Neumeier’s company in Hamburg, the twin brothers have worked their way up to become artists of international renown and recognition. Back during their studies at the Prague Conservatory, it was evident that the Bubeníčeks possessed a unique potential, which earned them accolades at the Prix de Lausanne. Those who are familiar with this prestigious competition know that passing through the sieve of the individual rounds requires great effort, talent and flawless accomplishment. The Bubeníčeks, however, did not rest on their laurels and duly went on to build up careers. They received support from their parents, former circus artistes, who initially passed on to their sons their skills and have always intensively shared in the successes Jiří and Otto have garnered.

Time runs fast, and 20 years have now passed since Otto and Jiří Bubeníček moved to Germany. Over that time, they have portrayed numerous great roles and received many international prizes. They keep themselves in tip-top shape and, owing to their diligence and openness to everything creative, have been invited to work with renowned ballet companies worldwide. In the realm of dance, the Bubeníček brothers have become a scarce phenomenon, not only owing to their identical looks but, most significantly, their bold individualities and dazzling charisma.

The names of the Bubeníček twins have become a distinguished and reputable brand not only in the world of dance. Their performances are also attended by those who do not regularly savour dance. They feel they simply have to see the Bubeníčeks, since the brothers’ lustre is comparable to that of some celebrated opera divas. Since their first – and fateful – engagement at John Neumeier’s company in Hamburg, the twin brothers have worked their way up to become artists of international renown and recognition. Back during their studies at the Prague Conservatory, it was evident that the Bubeníčeks possessed a unique potential, which earned them accolades at the Prix de Lausanne. Those who are familiar with this prestigious competition know that passing through the sieve of the individual rounds requires great effort, talent and flawless accomplishment. The Bubeníčeks, however, did not rest on their laurels and duly went on to build up careers. They received support from their parents, former circus artistes, who initially passed on to their sons their skills and have always intensively shared in the successes Jiří and Otto have garnered.

Time runs fast, and 20 years have now passed since Otto and Jiří Bubeníček moved to Germany. Over that time, they have portrayed numerous great roles and received many international prizes. They keep themselves in tip-top shape and, owing to their diligence and openness to everything creative, have been invited to work with renowned ballet companies worldwide. In the realm of dance, the Bubeníček brothers have become a scarce phenomenon, not only owing to their identical looks but, most significantly, their bold individualities and dazzling charisma.

John Neumeier’s Hamburg Ballett has only visited Prague once: back in 2000 they performed at the National Theatre their production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in which Jiří danced Oberon, Otto portrayed Puck and the Czech ballerina Adéla Pollertová excelled in the comic role of Helena. Nine years later, the brothers appeared in Prague with their gala evening Bubeníček and Friends, in 2011 they joined a project at the chateau in Velké Losiny. This year, they presented the programme Les Ballets Bubeníček, made up solely of their own works. Seven years ago the twins went their separate ways. Jiří left Hamburg to become a principal dancer at the Semperoper in Dresden, where, as he told journalists in Prague, the company’s artistic director, Aaron S. Watkin, afforded him more time to devote to choreographing. Otto, on the other hand, began paying greater attention to composing and set design. Accordingly, the Bubeníček brothers gradually began bringing to bear their many talents. Otto, who composes music on the computer, said that in Germany his “brother bought an organ, which wearied him”, whereas he himself was “enchanted by the instrument”.

The white colour of innocence

When the twins started to work on the ballet Le Souffle de l’Esprit, Otto arrived at the decision to use the colour white as a symbol of purity in the costumes, designed as simple shirts and trousers. He supplemented the sets with a back projection, showing parts of Leonardo da Vinci’s pictures (pencil drawings and other works, including the oil painting St. John the Baptist, with John pointing with a finger of his right hand up to heaven, as do the dancers at the end of one of the scenes). The choreography employs Otto’s compositions Silence and Angel’s Departure. The sound of sea waves is heard, with three dancers moving forward, their arms giving the impression of taking off, and then returning to the horizon, softly landing on the ground and listening to its tremble. The choreography is a belated bidding farewell to Olga and Marie, the brothers’ late grandmothers. It is replete with nostalgic moments, standstills and pure lines. Created for four male dancers and three ballerinas, it includes solos, duets and chorus passages. The motion current unwinds in spirals, which flow into unique figures with bold pervading of arms around the head. Everything is perfectly timed and the movement precisely phrased in ever-changing shapes – stretching and subsequently shrinking in a continuous cycle of transformations. Now and then, a spiral is disrupted by a dancer’s direct entering the space, with his torso rectilinearily bending forward and the arms stretched forward with a sharply bent wrist downwards. In addition to his brother’s pieces, Jiří Bubeníček chose Johann Sebastian Bach’s angelically sounding Air and Fugue in G minor, as well as Johann Pachelbel’s Canon in D major. The music arouses emotions and its beautiful melodies are captured in dance replete with elegance and ethereality. The next dance piece, Toccata, dedicated to the Bubeníčeks’ mother, reflects the emotions of romantic interpersonal relations. After four months of working on the choreography, Jiří came to the studio and taught the dancers every step and its nuances, leaving no scope for improvisation. Three couples, distinguished by green, blue and violet costume components, render different moods and atmospheres. Jiří Bubeníček prepared the choreography for New York City Ballet, after receiving a commission from its artistic director, Peter Martins, and Toccata was premiered on 13 May 2009. For Otto, it was the sixth work of his brother’s for which he had composed music and the first that he accompanied with a live performance – his piano stood behind a black, transparent curtain, with the remaining members of the orchestra (the cellist and the violinist) placed on an elevated spot. According to Jiří Bubeníček, it appeared as though the players were floating in the air. The choreography blends duets and solos, and concludes with a trio of a ballerina and two partners. We can see tender touches, embraces, as well as defiance. Jiří was inspired by Neo-Classicism, placing greater emphasis on poses, precise figurations, pirouettes en pointe and the movement led in vertical lines. Toccata comes across as an aesthetically tuned up vision, encompassing shards of passion, disappointment and joy.

An up-to-date, timeless Faun

The next dance piece, Toccata, dedicated to the Bubeníčeks’ mother, reflects the emotions of romantic interpersonal relations. After four months of working on the choreography, Jiří came to the studio and taught the dancers every step and its nuances, leaving no scope for improvisation. Three couples, distinguished by green, blue and violet costume components, render different moods and atmospheres. Jiří Bubeníček prepared the choreography for New York City Ballet, after receiving a commission from its artistic director, Peter Martins, and Toccata was premiered on 13 May 2009. For Otto, it was the sixth work of his brother’s for which he had composed music and the first that he accompanied with a live performance – his piano stood behind a black, transparent curtain, with the remaining members of the orchestra (the cellist and the violinist) placed on an elevated spot. According to Jiří Bubeníček, it appeared as though the players were floating in the air. The choreography blends duets and solos, and concludes with a trio of a ballerina and two partners. We can see tender touches, embraces, as well as defiance. Jiří was inspired by Neo-Classicism, placing greater emphasis on poses, precise figurations, pirouettes en pointe and the movement led in vertical lines. Toccata comes across as an aesthetically tuned up vision, encompassing shards of passion, disappointment and joy.

An up-to-date, timeless Faun  Within the Les Ballets Bubeníček programme, Jiří Bubeníček also showcased his qualities as a story-teller. At the time of its origin, the ballet L'après-midi d'un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun) caused a great scandal, and not only owing to its subject matter. Heated debates were also aroused by Vaslav Nijinsky’s choreography, depicting the Faun’s erotic dreams. Claude Debussy’s Impressionist composition of the same name, set to Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem, inspired Nijinsky to create the legendary piece, which would have a profound impact of the aesthetics of dance. Nijinsky conceived his ballet as a revived Ancient bas-relief, hence he employed poses with dancers turned with their profiles, and came up with innovative formations, fragments of which are also applied by Jiří Bubeníček. To mark the centenary of the world premiere of the L'après-midi d'un faune in 1912, the choreography was created for the Semperoper Ballett in Dresden.

Jiří Bubeníček presents a new view of the theme and its treatment. The idea for creating the choreography occurred to him when he came across a shocking media report about hushed-up sexual abuse of boys in the Church milieu. He detected an interconnection between the archetypal signs of the Faun in Ancient mythology and the contemporary world and duly conceived a powerful, compelling work. Six dancers sit at an oblong white table placed in the middle of the stage; a priest clad in a black gown with a red sleeveless coat over it is seated on a throne at the head of the table. The six dancers (probably representing novices) wear brightly coloured tunics with large side splits. Mass is served, the boys pray and subsequently cast their robes aside, remaining in flesh-coloured shorts. All of a sudden they appear to feel a sense of relief, breathing freely, tossing away together with their clothes a certain pretension. At the end of the mass, the priest absolves them, brushing the face of one of the youths, yet this stroke is only seemingly innocent. The boy touches his cheek, sensing something unusual, and is confused and terrified. Debussy’s music begins to sound and the Faun crawls out from behind the white throne. He symbolises irresistible desire, temptation, lust and sinful ideas. The Faun enters the impassioned male duet, in which the priest manipulates his victim. An initially thin white cross on the backdrop slowly widens, turns purple, before diminishing in the end. In vain does the boy try to resist the priest’s unwelcome advances and touches. The Faun keeps provoking with his sensuousness – in some moments, his dance refers to Nijinsky’s version. Desire and lust overwhelm the priest, who ultimately attains what he wants by means of violence. Afterwards, the Faun sits astride the throne, taking up the priest’s place, his arms caressing his body and his head slowly turning.

Jiří Bubeníček has succeeded in conveying the delicate topic into a theatrically consistent form, with each movement and action set in the space, and the flowing of arms contrasting with the shooting of legs. Raphael Coumes-Marquet, in the role of the priest, is an impressive figure, capturing the ambivalence of the character and bringing him to the climax of satisfaction. Claudio Cangialosi, as the Faun, is alluring, lustful and seductive, giving an accurate and eager portrayal of the Faun’s caprices. Bubeníček’s Faun is earnest, provocative and painful alike.

Within the Les Ballets Bubeníček programme, Jiří Bubeníček also showcased his qualities as a story-teller. At the time of its origin, the ballet L'après-midi d'un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun) caused a great scandal, and not only owing to its subject matter. Heated debates were also aroused by Vaslav Nijinsky’s choreography, depicting the Faun’s erotic dreams. Claude Debussy’s Impressionist composition of the same name, set to Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem, inspired Nijinsky to create the legendary piece, which would have a profound impact of the aesthetics of dance. Nijinsky conceived his ballet as a revived Ancient bas-relief, hence he employed poses with dancers turned with their profiles, and came up with innovative formations, fragments of which are also applied by Jiří Bubeníček. To mark the centenary of the world premiere of the L'après-midi d'un faune in 1912, the choreography was created for the Semperoper Ballett in Dresden.

Jiří Bubeníček presents a new view of the theme and its treatment. The idea for creating the choreography occurred to him when he came across a shocking media report about hushed-up sexual abuse of boys in the Church milieu. He detected an interconnection between the archetypal signs of the Faun in Ancient mythology and the contemporary world and duly conceived a powerful, compelling work. Six dancers sit at an oblong white table placed in the middle of the stage; a priest clad in a black gown with a red sleeveless coat over it is seated on a throne at the head of the table. The six dancers (probably representing novices) wear brightly coloured tunics with large side splits. Mass is served, the boys pray and subsequently cast their robes aside, remaining in flesh-coloured shorts. All of a sudden they appear to feel a sense of relief, breathing freely, tossing away together with their clothes a certain pretension. At the end of the mass, the priest absolves them, brushing the face of one of the youths, yet this stroke is only seemingly innocent. The boy touches his cheek, sensing something unusual, and is confused and terrified. Debussy’s music begins to sound and the Faun crawls out from behind the white throne. He symbolises irresistible desire, temptation, lust and sinful ideas. The Faun enters the impassioned male duet, in which the priest manipulates his victim. An initially thin white cross on the backdrop slowly widens, turns purple, before diminishing in the end. In vain does the boy try to resist the priest’s unwelcome advances and touches. The Faun keeps provoking with his sensuousness – in some moments, his dance refers to Nijinsky’s version. Desire and lust overwhelm the priest, who ultimately attains what he wants by means of violence. Afterwards, the Faun sits astride the throne, taking up the priest’s place, his arms caressing his body and his head slowly turning.

Jiří Bubeníček has succeeded in conveying the delicate topic into a theatrically consistent form, with each movement and action set in the space, and the flowing of arms contrasting with the shooting of legs. Raphael Coumes-Marquet, in the role of the priest, is an impressive figure, capturing the ambivalence of the character and bringing him to the climax of satisfaction. Claudio Cangialosi, as the Faun, is alluring, lustful and seductive, giving an accurate and eager portrayal of the Faun’s caprices. Bubeníček’s Faun is earnest, provocative and painful alike.

Two in one

Two in one

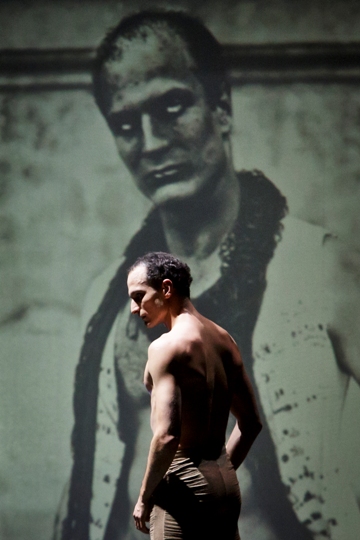

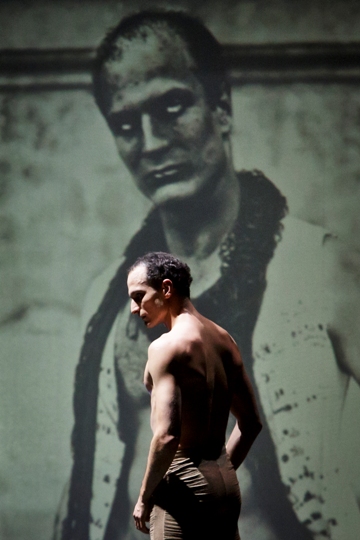

Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray first captivated the Bubeníček brothers’ father, who saw in it a theme interesting for his sons. Later on, Otto discovered Keith Jarrett’s music, got an idea of how to conceive the story on stage, and wrote a scenario. At the time, Jiří did not occupy himself with the theme, hence the choreography was only presented in 2011, within a performance at the chateau in Velké Losiny. Wilde’s work lends itself to various interpretations: it not only deals with the other, less savoury, side of the individual, it is also about the human longing to stay young and beautiful. In Chapter II, Dorian Gray says: “How sad it is! I shall grow old, and horrible, and dreadful. But this picture will remain always young.” A photograph of one of the twins (Jiří) hangs on stage, Otto, clad in brightly coloured draped trousers, stands in front of it and begins recounting the story of his doubts, misdemeanours, losses and discoveries. Jiří appears, embodying temptation, bad conscience - an integral part of Dorian Gray- and changes his clothes: now he is a dandy in wide black trousers, then an elegant gentleman with a dinner jacket and cane, yet always a certain enticer, pointing at the situations that make his “rival” uneasy and cause him sorrow. The black-and-white portrait slowly turns black, withers, the youthful face grows old and the smile wanes. The end is inevitable. Otto dances a duet with his beloved, then proceeds to kill her. Their duet is tender, from gentle hand touching to refined lifts and moments in which the ballerina lightly whirls above the floor. In the final collision, Dorian Gray – Otto – grinds his alter ego into the ground, destroys it and, after a while, he too remains motionless, huddled in front of the picture, on which he is young again. Good things come about naturally

Seeing the Bubeníček brothers in action is a great experience and the impressions from their performance stay with you for a long time afterwards. Jiří and Otto are masters of their bodies, which they command to the tiniest detail, and their profound knowledge of the academic technique and ability to discover further possibilities of the creative direction make them sensitive artists. When working with John Neumeier, they “contracted” a pervasive and provident insight, learned to see dance as an integral part of music and the visual arts. Their works bring about a new dance quality, one reflecting the mastery of the dance craft, which they enter with the rare ability to find precise setting of movement revealing the forgotten corners of the human body and mind. What’s more, in the Les Ballets Bubeníček formation, they work with people they like being with, and since all its members participate in projects exceeding the framework of the workloads at their respective theatres, they are bound together by mutual support and respect – bearing witness to this was the participation of all the dancers at a meeting at noon on 12 Sunday 2014 following the first performance, even though the session was announced as being with the Bubeníčeks only. Iana Salenko, Anna Merkulova, Elena Vostrotina, Duosi Zhu, Raquél Martinéz, Claudio Cangialosi, Raphaël Coumes-Marquet, Fabien Voranger, Jón Vallejo, Francesco Pio Ricci, Michael Tucker, Johannes Schmidt and Jan Oratynski hail from various corners of the world. With the exception of Arsen Mehrabyan, principal dancer of the Swedish Royal Ballet, all of them are engaged at the Semperoper in Dresden. They rehearsed the Les Ballets Bubeníček project on their evenings off, they trust Jiří and Otto, and are keen to work with them, as was evident from their impeccable performances. Otto is of the opinion that “good things come about naturally”. And the good news is that the Bubeníček brothers seek out and embrace them.

Otto is of the opinion that “good things come about naturally”. And the good news is that the Bubeníček brothers seek out and embrace them.

The review refers to the performance on 11 January 2014 at the National Theatre in Prague. Les Ballets Bubeníček Le Souffle de l’Esprit

Choreography: Jiří Bubeníček

Music: Johann Sebastian Bach, Johann Pachelbel and Otto BubeníčekSets, Costumes and video: Otto Bubeníček

Lighting design: Jiří Bubeníček a Fabio Antoci Toccata

Choreography: Jiří Bubeníček

Music and costumes: Otto Bubeníček

Lighting design: Jiří Bubeníček and Fabio Antoci Faun

Choreography: Jiří Bubeníček

Music: Francis Poulenc and Claude Debussy

Sets and costumes: Otto Bubeníček

Lighting design: Fabio Antoci and Jiří Bubeníček The Picture of Dorian Gray

Choreography: Jiří Bubeníček

Music: Keith Jarrett and Bruno Moretti

Costumes: Denisa Nová

Sets: Otto Bubeníček

Lighting design: Jiří Bubeníček and Fabio Antoci Photo: Martin Divíšek

Translation: Hilda Hearne

When the twins started to work on the ballet Le Souffle de l’Esprit, Otto arrived at the decision to use the colour white as a symbol of purity in the costumes, designed as simple shirts and trousers. He supplemented the sets with a back projection, showing parts of Leonardo da Vinci’s pictures (pencil drawings and other works, including the oil painting St. John the Baptist, with John pointing with a finger of his right hand up to heaven, as do the dancers at the end of one of the scenes). The choreography employs Otto’s compositions Silence and Angel’s Departure. The sound of sea waves is heard, with three dancers moving forward, their arms giving the impression of taking off, and then returning to the horizon, softly landing on the ground and listening to its tremble. The choreography is a belated bidding farewell to Olga and Marie, the brothers’ late grandmothers. It is replete with nostalgic moments, standstills and pure lines. Created for four male dancers and three ballerinas, it includes solos, duets and chorus passages. The motion current unwinds in spirals, which flow into unique figures with bold pervading of arms around the head. Everything is perfectly timed and the movement precisely phrased in ever-changing shapes – stretching and subsequently shrinking in a continuous cycle of transformations. Now and then, a spiral is disrupted by a dancer’s direct entering the space, with his torso rectilinearily bending forward and the arms stretched forward with a sharply bent wrist downwards. In addition to his brother’s pieces, Jiří Bubeníček chose Johann Sebastian Bach’s angelically sounding Air and Fugue in G minor, as well as Johann Pachelbel’s Canon in D major. The music arouses emotions and its beautiful melodies are captured in dance replete with elegance and ethereality.

The next dance piece, Toccata, dedicated to the Bubeníčeks’ mother, reflects the emotions of romantic interpersonal relations. After four months of working on the choreography, Jiří came to the studio and taught the dancers every step and its nuances, leaving no scope for improvisation. Three couples, distinguished by green, blue and violet costume components, render different moods and atmospheres. Jiří Bubeníček prepared the choreography for New York City Ballet, after receiving a commission from its artistic director, Peter Martins, and Toccata was premiered on 13 May 2009. For Otto, it was the sixth work of his brother’s for which he had composed music and the first that he accompanied with a live performance – his piano stood behind a black, transparent curtain, with the remaining members of the orchestra (the cellist and the violinist) placed on an elevated spot. According to Jiří Bubeníček, it appeared as though the players were floating in the air. The choreography blends duets and solos, and concludes with a trio of a ballerina and two partners. We can see tender touches, embraces, as well as defiance. Jiří was inspired by Neo-Classicism, placing greater emphasis on poses, precise figurations, pirouettes en pointe and the movement led in vertical lines. Toccata comes across as an aesthetically tuned up vision, encompassing shards of passion, disappointment and joy.

An up-to-date, timeless Faun

The next dance piece, Toccata, dedicated to the Bubeníčeks’ mother, reflects the emotions of romantic interpersonal relations. After four months of working on the choreography, Jiří came to the studio and taught the dancers every step and its nuances, leaving no scope for improvisation. Three couples, distinguished by green, blue and violet costume components, render different moods and atmospheres. Jiří Bubeníček prepared the choreography for New York City Ballet, after receiving a commission from its artistic director, Peter Martins, and Toccata was premiered on 13 May 2009. For Otto, it was the sixth work of his brother’s for which he had composed music and the first that he accompanied with a live performance – his piano stood behind a black, transparent curtain, with the remaining members of the orchestra (the cellist and the violinist) placed on an elevated spot. According to Jiří Bubeníček, it appeared as though the players were floating in the air. The choreography blends duets and solos, and concludes with a trio of a ballerina and two partners. We can see tender touches, embraces, as well as defiance. Jiří was inspired by Neo-Classicism, placing greater emphasis on poses, precise figurations, pirouettes en pointe and the movement led in vertical lines. Toccata comes across as an aesthetically tuned up vision, encompassing shards of passion, disappointment and joy.

An up-to-date, timeless Faun  Within the Les Ballets Bubeníček programme, Jiří Bubeníček also showcased his qualities as a story-teller. At the time of its origin, the ballet L'après-midi d'un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun) caused a great scandal, and not only owing to its subject matter. Heated debates were also aroused by Vaslav Nijinsky’s choreography, depicting the Faun’s erotic dreams. Claude Debussy’s Impressionist composition of the same name, set to Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem, inspired Nijinsky to create the legendary piece, which would have a profound impact of the aesthetics of dance. Nijinsky conceived his ballet as a revived Ancient bas-relief, hence he employed poses with dancers turned with their profiles, and came up with innovative formations, fragments of which are also applied by Jiří Bubeníček. To mark the centenary of the world premiere of the L'après-midi d'un faune in 1912, the choreography was created for the Semperoper Ballett in Dresden.

Jiří Bubeníček presents a new view of the theme and its treatment. The idea for creating the choreography occurred to him when he came across a shocking media report about hushed-up sexual abuse of boys in the Church milieu. He detected an interconnection between the archetypal signs of the Faun in Ancient mythology and the contemporary world and duly conceived a powerful, compelling work. Six dancers sit at an oblong white table placed in the middle of the stage; a priest clad in a black gown with a red sleeveless coat over it is seated on a throne at the head of the table. The six dancers (probably representing novices) wear brightly coloured tunics with large side splits. Mass is served, the boys pray and subsequently cast their robes aside, remaining in flesh-coloured shorts. All of a sudden they appear to feel a sense of relief, breathing freely, tossing away together with their clothes a certain pretension. At the end of the mass, the priest absolves them, brushing the face of one of the youths, yet this stroke is only seemingly innocent. The boy touches his cheek, sensing something unusual, and is confused and terrified. Debussy’s music begins to sound and the Faun crawls out from behind the white throne. He symbolises irresistible desire, temptation, lust and sinful ideas. The Faun enters the impassioned male duet, in which the priest manipulates his victim. An initially thin white cross on the backdrop slowly widens, turns purple, before diminishing in the end. In vain does the boy try to resist the priest’s unwelcome advances and touches. The Faun keeps provoking with his sensuousness – in some moments, his dance refers to Nijinsky’s version. Desire and lust overwhelm the priest, who ultimately attains what he wants by means of violence. Afterwards, the Faun sits astride the throne, taking up the priest’s place, his arms caressing his body and his head slowly turning.

Jiří Bubeníček has succeeded in conveying the delicate topic into a theatrically consistent form, with each movement and action set in the space, and the flowing of arms contrasting with the shooting of legs. Raphael Coumes-Marquet, in the role of the priest, is an impressive figure, capturing the ambivalence of the character and bringing him to the climax of satisfaction. Claudio Cangialosi, as the Faun, is alluring, lustful and seductive, giving an accurate and eager portrayal of the Faun’s caprices. Bubeníček’s Faun is earnest, provocative and painful alike.

Within the Les Ballets Bubeníček programme, Jiří Bubeníček also showcased his qualities as a story-teller. At the time of its origin, the ballet L'après-midi d'un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun) caused a great scandal, and not only owing to its subject matter. Heated debates were also aroused by Vaslav Nijinsky’s choreography, depicting the Faun’s erotic dreams. Claude Debussy’s Impressionist composition of the same name, set to Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem, inspired Nijinsky to create the legendary piece, which would have a profound impact of the aesthetics of dance. Nijinsky conceived his ballet as a revived Ancient bas-relief, hence he employed poses with dancers turned with their profiles, and came up with innovative formations, fragments of which are also applied by Jiří Bubeníček. To mark the centenary of the world premiere of the L'après-midi d'un faune in 1912, the choreography was created for the Semperoper Ballett in Dresden.

Jiří Bubeníček presents a new view of the theme and its treatment. The idea for creating the choreography occurred to him when he came across a shocking media report about hushed-up sexual abuse of boys in the Church milieu. He detected an interconnection between the archetypal signs of the Faun in Ancient mythology and the contemporary world and duly conceived a powerful, compelling work. Six dancers sit at an oblong white table placed in the middle of the stage; a priest clad in a black gown with a red sleeveless coat over it is seated on a throne at the head of the table. The six dancers (probably representing novices) wear brightly coloured tunics with large side splits. Mass is served, the boys pray and subsequently cast their robes aside, remaining in flesh-coloured shorts. All of a sudden they appear to feel a sense of relief, breathing freely, tossing away together with their clothes a certain pretension. At the end of the mass, the priest absolves them, brushing the face of one of the youths, yet this stroke is only seemingly innocent. The boy touches his cheek, sensing something unusual, and is confused and terrified. Debussy’s music begins to sound and the Faun crawls out from behind the white throne. He symbolises irresistible desire, temptation, lust and sinful ideas. The Faun enters the impassioned male duet, in which the priest manipulates his victim. An initially thin white cross on the backdrop slowly widens, turns purple, before diminishing in the end. In vain does the boy try to resist the priest’s unwelcome advances and touches. The Faun keeps provoking with his sensuousness – in some moments, his dance refers to Nijinsky’s version. Desire and lust overwhelm the priest, who ultimately attains what he wants by means of violence. Afterwards, the Faun sits astride the throne, taking up the priest’s place, his arms caressing his body and his head slowly turning.

Jiří Bubeníček has succeeded in conveying the delicate topic into a theatrically consistent form, with each movement and action set in the space, and the flowing of arms contrasting with the shooting of legs. Raphael Coumes-Marquet, in the role of the priest, is an impressive figure, capturing the ambivalence of the character and bringing him to the climax of satisfaction. Claudio Cangialosi, as the Faun, is alluring, lustful and seductive, giving an accurate and eager portrayal of the Faun’s caprices. Bubeníček’s Faun is earnest, provocative and painful alike.  Two in one

Two in one Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray first captivated the Bubeníček brothers’ father, who saw in it a theme interesting for his sons. Later on, Otto discovered Keith Jarrett’s music, got an idea of how to conceive the story on stage, and wrote a scenario. At the time, Jiří did not occupy himself with the theme, hence the choreography was only presented in 2011, within a performance at the chateau in Velké Losiny. Wilde’s work lends itself to various interpretations: it not only deals with the other, less savoury, side of the individual, it is also about the human longing to stay young and beautiful. In Chapter II, Dorian Gray says: “How sad it is! I shall grow old, and horrible, and dreadful. But this picture will remain always young.” A photograph of one of the twins (Jiří) hangs on stage, Otto, clad in brightly coloured draped trousers, stands in front of it and begins recounting the story of his doubts, misdemeanours, losses and discoveries. Jiří appears, embodying temptation, bad conscience - an integral part of Dorian Gray- and changes his clothes: now he is a dandy in wide black trousers, then an elegant gentleman with a dinner jacket and cane, yet always a certain enticer, pointing at the situations that make his “rival” uneasy and cause him sorrow. The black-and-white portrait slowly turns black, withers, the youthful face grows old and the smile wanes. The end is inevitable. Otto dances a duet with his beloved, then proceeds to kill her. Their duet is tender, from gentle hand touching to refined lifts and moments in which the ballerina lightly whirls above the floor. In the final collision, Dorian Gray – Otto – grinds his alter ego into the ground, destroys it and, after a while, he too remains motionless, huddled in front of the picture, on which he is young again. Good things come about naturally

Seeing the Bubeníček brothers in action is a great experience and the impressions from their performance stay with you for a long time afterwards. Jiří and Otto are masters of their bodies, which they command to the tiniest detail, and their profound knowledge of the academic technique and ability to discover further possibilities of the creative direction make them sensitive artists. When working with John Neumeier, they “contracted” a pervasive and provident insight, learned to see dance as an integral part of music and the visual arts. Their works bring about a new dance quality, one reflecting the mastery of the dance craft, which they enter with the rare ability to find precise setting of movement revealing the forgotten corners of the human body and mind. What’s more, in the Les Ballets Bubeníček formation, they work with people they like being with, and since all its members participate in projects exceeding the framework of the workloads at their respective theatres, they are bound together by mutual support and respect – bearing witness to this was the participation of all the dancers at a meeting at noon on 12 Sunday 2014 following the first performance, even though the session was announced as being with the Bubeníčeks only. Iana Salenko, Anna Merkulova, Elena Vostrotina, Duosi Zhu, Raquél Martinéz, Claudio Cangialosi, Raphaël Coumes-Marquet, Fabien Voranger, Jón Vallejo, Francesco Pio Ricci, Michael Tucker, Johannes Schmidt and Jan Oratynski hail from various corners of the world. With the exception of Arsen Mehrabyan, principal dancer of the Swedish Royal Ballet, all of them are engaged at the Semperoper in Dresden. They rehearsed the Les Ballets Bubeníček project on their evenings off, they trust Jiří and Otto, and are keen to work with them, as was evident from their impeccable performances.

Otto is of the opinion that “good things come about naturally”. And the good news is that the Bubeníček brothers seek out and embrace them.

Otto is of the opinion that “good things come about naturally”. And the good news is that the Bubeníček brothers seek out and embrace them. The review refers to the performance on 11 January 2014 at the National Theatre in Prague. Les Ballets Bubeníček Le Souffle de l’Esprit

Choreography: Jiří Bubeníček

Music: Johann Sebastian Bach, Johann Pachelbel and Otto BubeníčekSets, Costumes and video: Otto Bubeníček

Lighting design: Jiří Bubeníček a Fabio Antoci Toccata

Choreography: Jiří Bubeníček

Music and costumes: Otto Bubeníček

Lighting design: Jiří Bubeníček and Fabio Antoci Faun

Choreography: Jiří Bubeníček

Music: Francis Poulenc and Claude Debussy

Sets and costumes: Otto Bubeníček

Lighting design: Fabio Antoci and Jiří Bubeníček The Picture of Dorian Gray

Choreography: Jiří Bubeníček

Music: Keith Jarrett and Bruno Moretti

Costumes: Denisa Nová

Sets: Otto Bubeníček

Lighting design: Jiří Bubeníček and Fabio Antoci Photo: Martin Divíšek

Translation: Hilda Hearne