Before we move onto the festival programme, I would like to ask about your background?

I was born in Portugal and started studying biology at the University of Lisbon before moving into dance and performance studies, which I graduated in. For a couple of years, I worked at a production level for the University, developing my own work and performing for other choreographers. Then I was invited to join the O Espaço do Tempo team, one of the most renewed residence centres in Portugal, directed by choreographer Rui Horta. I assisted the artistic director in curating not only the residence programme, but also the performances. After four years, I moved back to Lisbon, where I joined the Alkantara festival team for two years, co-directing it with Thomas Walgrave. He had a theatre background, whereas mine was dance. It was a good combination because Alkantara is a multidisciplinary festival, presenting theatre, performance, and dance pieces. In 2012, I was invited by the newly appointed managing and artistic director, Annemie Vanackere, to join the new team at the HAU Hebbel am Ufer as a dance and performance curator. It was also at that time that Tanz im August became a HAU festival and part of its overall structure (such as the administration and graphic design), with Annemie as its managing director, but with an independent artistic director,curatorial and production team. Last year I was put forward to the city to take over from Virve (Sutinen) after nine years. Of course, I was happy to join the TiA team as their artistic director! Parallel to this process, the programme team at the HAU were looking for a new dance and performance curator and found Petra Poelzl, who joined the HAU in April 2022.

What are your curatorial influences, references, and lines of programming for TiA?

Firstly, I would like to highlight that creating a programme specifically for the festival is a very different experience on many levels from designing it for the season. The festival is held during a unique time of year (the month of August). The festival has a very strong profile when it comes to dance because it is one of the few moments during the year that dance is performed in the different theatres of Berlin as part of one unique programme, all in a short period of time. One of the most important features of the festival is showing large-scale productions that are uncommon in theatres which usually host dance productions. Nevertheless, I think the scene in Berlin is changing a bit, especially in the last three years. For example, you now also have bigger venues, like the Volksbühne, or the Berliner Festspiele, staging dance performances and I am quite happy about that. But the TiA festival still plays an important role in showing those pieces, as well as reflecting on the current state of contemporary dance.

Your previous programmes for HAU offered a fascinating intersection between, for instance, post-colonialist informed pieces and pure dance performances. When you started ideating your first edition of TiA, were there any changes in curatorial approach compared to your previous experiences?

We just spoke about temporality but there is also the connection with the spaces. The programme for HAU is mostly presented in three venues, HAU1, 2, 3, and occasionally in collaboration with other venues and in other locations. The festival is historically done in partnership with different venues in the city, with capacities ranging between 100 and 1000. It allows me to stage pieces on varying scales. The festival also makes it possible to perform projects outside of the theatre, in public spaces, which is something that I have always seriously considered. This year, we have a project called Interconnecting Dance & Ecology which takes place in three of Berlin’s parks. As the name suggests, it aims to reflect upon the connection between dance and ecology. The pieces are a result of an open call selection to Berlin-based artists. We received around 220 applications from which a jury selected 22 artists.

I am also very keen to find ways to leave traces in the city after the festival ends. By this I mean, because of the nature of the festival, most of the companies arrive maybe two days before the show, they perform a couple of times, and then they leave. But I am always thinking what else can we do to embed more of these artists in the city, among its population and other Berlin artists. To this end, I went back to the first few editions of the festival, founded by Nele Hertling in 1989, as a source of inspiration. For Hertling, workshops were a relevant part of the festival and of the development of the connection between the international and the local scene. That happened in a very specific moment in Berlin’s history because the Wall came down that same year. Some years after the festival was founded, the workshops disappeared. I decided to bring the workshops back. This year, there are six workshops, all with different aims, designed for different people, but all accessible to everyone and not just for professionals.

So you are going backwards in order to move forward….

I see myself as part of a sequence with all the festival’s previous artistic directors and I feel connected to the history of the people who have worked at the festival. I am delighted to have the opportunity to be part of the festival. I always think a lot about continuity. Sometimes in the cultural field when there is a new artistic director, everything changes, provoking a big departure from the past. There is a new corporate identity, a new logo, completely new artists invited. Even though I value the need for renovation, I feel that, in amongst these huge changes, something gets lost. This year, there is a good mix between people that are new to the festival, but also artists that have featured at the festival in recent years. I do also believe that the Berlin audience is very faithful and curious to see the development of the artists they appreciate, so they are glad to welcome them back. The audience is interested in following the artist’s journey.

You mentioned the dance and ecology event in the parks. It is a topical issue at the moment, but it is also a public event embracing the parks of Berlin, which are always, as you (we) know, much loved by the city’s residents and are connected to the texture of the city on other levels. To what extent has your background as a biologist influenced your TiA programme? For instance, I read your text A Forest of Worlds, where the forest is seen as an organism able to interconnect on multiple levels.

The connection with biology is interesting because I gained experience in this area when I was at university, but after a period of working in the dance field, I became disconnected from it. When I was starting to conceptualise the festival, I do not know exactly how to explain it, but it came back to me again. Maybe it had to do with the pandemic. Everything we study forms us in some way, everything that we read is part of our universe, in our minds. I asked myself, ‘what if I start to think about the festival, about the programme using the tools I know from ecology and biology?’ This was an interesting kind of curatorial process for me, because it opened up many trains of thought. When putting together a programme, I always find it exciting to use different tools to think. It really matters what stories we use to tell other stories, and what ideas we bring to the table when we are developing the programme. Regarding the direct connection with nature, there is the park project, but there are also three other projects that reflect on the relationship between nature, geography, landscape, and culture. Furthermore, I started to consider the festival as having its own ecology, in terms of how things are interconnected, just as in a forest.

There was a moment during the pandemic, when we were thinking that when it was over, we should reimagine how we produce/make dance. Do you think that something has changed in dance curatorial work, globally speaking?

I agree with you: during the lockdowns, there was much discussion within the field with a desire for change. I do not see any massive changes now. I notice some very subtle changes, but not on a big structural level. There is a bigger reflection around mobility, on sustainability, and on the urgency of climate change, together with the influences of #MeToo and the Black Lives Matter movements. They are embedded and have become part of artistic creation. Nevertheless, in terms of macro-structures, I do not see a huge shift. Things are evolving more gradually. I have noticed that many people from the cultural field want a better balance between their home life and work life. There is also a conscious decision to slow down to a certain degree.

I think there is a ‘breath of fresh air’ that comes with the end of the pandemic. On a curatorial level, this is the first time I’ve not had to deal with the pandemic. Artistically speaking, even though some of the pieces still bear the mark of that time, the artists now have some distance from it and are moving forward.

We are also facing a big economic crisis. I have noticed this very clearly in the budget because things are more expensive than last year and we must take it into consideration for the programme.

When we started to develop the programme and the link to nature and sustainability, it was almost impossible not to also reflect on the festival’s structure. As a team we analysed our structure, the production process, how we arrange travel, accommodation, and food. We thought through how we could approach these things in a more sustainable way. We are following four principles to make this year’s festival more sustainable. The first one is related to mobility to varying degrees. For instance, when I travel to see shows or visiting artists, I always try to travel by train for an average of up to eight hours. I also tried to combine meetings and see more shows whenever I'm travelling. We also ask artists that live close to Germany, for example in France or Belgium, if they could come by train. Their response was very positive, and now a large proportion of those artists will come by train.

Another aspect is accommodation: we work with hotels which have a sustainability policy, in terms of water usage, and also where their food comes from. The third one has to do with printed materials: we selected Berlin-based printing companies that only use recycled paper and non-toxic ink, there is even a printing company that uses solar energy. The last point is to reduce the festival’s carbon footprint every year, a process that we are doing as part of HAU.

Could you please give me an insight into your artistic choices?

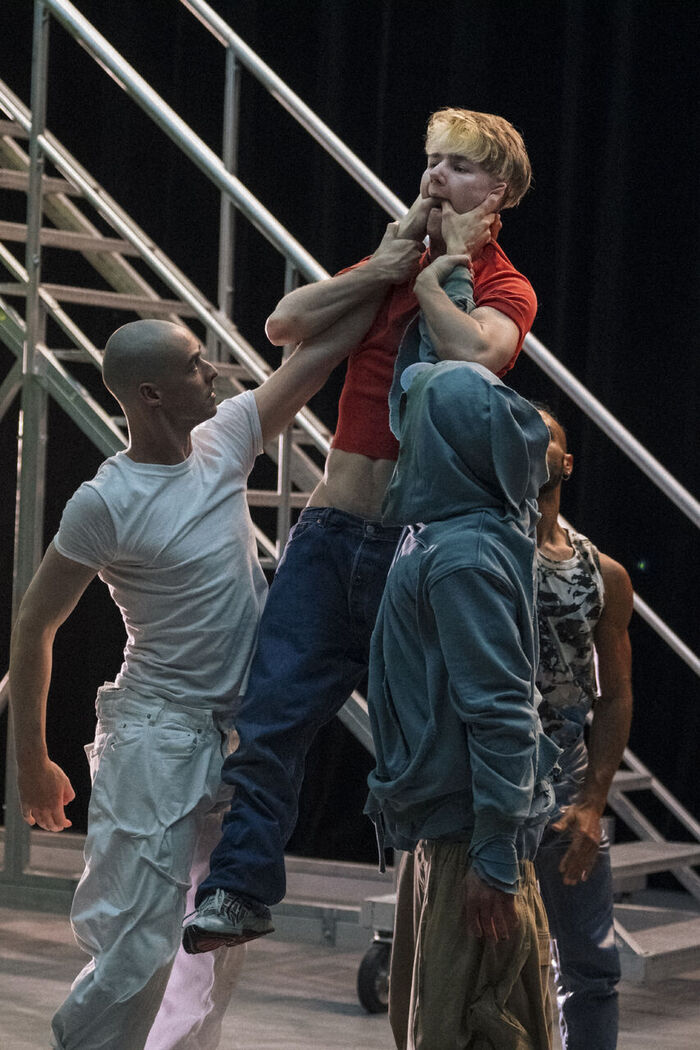

The programme is a mixture of artists that are less well-known in Berlin, artists who are coming for the first time, and artists that we have deemed important to bring back. There are basically three key themes for this festival: one is the connection with ecology and nature. The second is something that we have noticed in the last couple of years: choreographers that are using different dance styles in their pieces in a fluid way. For example, 15 years ago it was more common to see a specific heritage in a show, a movement legacy, the style they were using, whereas now I think this is more blurred. This is quite interesting because it means that dance has become a polyphonic creation and less of a fixed genre. It is not street dance or contemporary dance: it is street dance and contemporary dance. I do believe that a contemporary choreographer's goal is not just to extract elements from other styles but to invite people that belong to that specific dancing style community to work with. I think this almost horizontality between dance styles which occurs in the programme speaks for our times, much more diverse, much more spread, without one central vision.

Then the third one is connected to how artists use their body and movements to go back to storytelling, to reflect on the past. When we were coming out of lockdown, many artists had a desire to create new narratives, to look for new solutions. They thought that the way to do this was to go back to old stories and to tell them again with a different perspective. Furthermore, when you look at the past, you must deal with questions around colonialism because it is always present, it is a chance to think about the many layers that the old stories have.

Could you now relate artist names to your curatorial trends?

For dance and ecology, besides the park project I have already mentioned, Insel by Ginevra Panzetti and Enrico Ticconi is a reflection on how to connect to the landscape and geography of islands within our own psychology. Then SOTTOBOSCO by Chiara Bersani reflects on the disabled people’s access to nature: what if a disabled group of children wake up in the middle of the forest? The third one is Agata Siniarska’s null&void, where she looks at what happens to nature during times of war. This is also a chance to reflect on what is happening in Ukraine, which now has a lot more mines left in the ground. Once the war is over, which I hope it will be very soon, the mines will remain, representing not only a danger for humans, but also for animals and the soil.

Regarding the idea of mixing different dance styles, we have Marco da Silva Ferreira’s C A R C A Ç A as well as Prophétique (on est déjà né.es) by Nadia Beugré, a piece with trans women from Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire. They bring dance styles practised in nightclubs and other contexts and mix them with contemporary dance. The Ballet National de Marseille/(LA)HORDE’s piece AGE OF CONTENT represents the way this usually works. They integrate elements from pop culture, for instance TikTok, YouTube or Hollywood action films into the choreography.

In terms of storytelling as a tool for creation, a good example is Toi, moi, Tituba by Dorothée Munyaneza. It is a post-colonial investigation into Tituba, a Caribbean woman, taken as a slave to the United States and persecuted as part of the Salem witch trials, narrated from Tituba's own perspective. Another would be STRONG-BORN by Kat Válastur. ‘Strong born’ is the literal translation of the name Iphigenia, from Greek tragedy, a story of women’s sacrifice. Válastur makes a feminist statement, rejecting the idea of being a sacrificial victim. Finally, there is Libya by Radouan Mriziga. He has been investigating the Amazigh culture in the northern part of Africa, based on oral tradition, songs, and crafts.

What challenges are you facing as the new artistic director?

For me, challenges are always good. It has been a great process, starting in September 2022. I already knew some people from the team but some new faces also joined us. One of the most beautiful parts of performing arts, and especially dance, is that we need each other to make it happen, the artist needs the institution, the institution needs their teams, and we all need each other to make a project like a festival happen.

The kind of programming I am doing perhaps represents something of a challenge: a large cohort of the artists performing this year came from outside of Europe, so they don't have a Schengen Visa. This was a tough aspect that we have to deal with, that we have to support people with. Over the past year, the last few months in particular it has become an even bigger issue. Europe is closing its borders in a very systematic and strict way and making access much more difficult. You are from Italy, so maybe you have seen the government’s decision, supported by the European Union, to basically give money to governments like that of Tunisia to keep people away from Europe (Memorandum UE-Tunisia). This mechanism of building walls, creating a fortress around Europe, is a huge mistake, it will not work because everything is interconnected.

As a curator, my primary idea is that everything is interconnected. I cannot think about Europe or Germany without thinking about the rest of the world. Therefore, I am also keen to have a programme that reflects this interconnection. I also feel that it is not only me that is responding to the current situation but the artists as well: we are all together in this moment, trying to understand what’s happening, what’s urgent, and how we can get through it. Maybe because performative arts always take place in the present moment and react to it.

RICARDO CORREIA CARMONA (1978 - Portugal)

Ricard Correia Carmona began studying Biology but changed to Dance and Performance Studies in Lisbon, graduating in 2003. He then worked as a producer and between 2005 and 2009, joining the residence centre O Espaço do Tempo. From 2010 to 2012 he worked at the Alkantara Festival in Lisbon assisting with the artistic direction and he later joined the general direction. In August 2012 he moved to Berlin, taking on the role of Dance Curator of the HAU Hebbel am Ufer theatre where he worked until August 2022. From September 2022, he has been in charge of the artistic direction of HAU’s festival, Tanz im August, where he currently works.

The interview took place on the 3rd August 2023 in the offices of HAU Hebbel Am Ufer (Berlin).