Artistic director Carmona calls this festival edition “an archipelago of affinities”. Beyond the poetic dimension of its image, which is certainly appropriate in a context where dances from different parts of the world are set in various theatrical places, I also imagine the difficulties and adventures that may lie behind such a journey, especially with a storm on the horizon.

The storm threatening German and specifically Berlin-based cultural workers is the new 2025 budget proposal of the Federal Cultural Fund with its proposed drastic cuts (almost half of the 2024 budget). At a Berlin level, the expected cuts of 10-12% will have devastating consequences for the entire independent scene and dance in particular. Tough times lie ahead, to put it mildly. The festival management is concerned about this possible future situation, so it is no coincidence that all the festival locations offer informative flyers regarding current forms of protest.

The festival’s motto is reflected in its visual campaign through references to the underwater world. In Annemie Vanackere’s words (Artistic and Managing Director of HAU, organising body of Tanz Im August) this reminds us that the work to preserve the sea begins right here, in cities. As we can read in the festival’s sustainability directions, environmental awareness is important to the festival this year too.

On Intersecting Languages

Three pieces made me reflect on the possibility of using the scenic form of dance, with its various meanings and specific elements, as a possible (or impossible) means of constructing a common language.

Fampitaha, fampita, fampitàna (Comparison, transmission, rivalry), premiered at HAU2, is a dense choreographic piece, where dance, theatre, and songs intersect to address issues such as post-diaspora lives and cultural legacies that are about to be lost. Its choreographer Soa Ratsifandrihana trained in Paris and dances in Brussels with Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker's Rosas. Starting with oral narratives from specific countries of origin, Ratsifandrihana, along with two other dancers and a musician, present themselves as various generations of French immigrants with roots in Madagascar, Martinique, and Haïti. They tell the story of colonised peoples creating their own Creole culture and move through contemporary influenced choreographic movements such as walking, drawing at a ninety-degree angle on the stage, or rolling on the floor. Then they reach a crux: a tongue-twister in the imposed languages (English and French) that cannot be unravelled as it appears impossible to pronounce. This is countered by a different tongue-twister in their mother tongue, Malagasy, which seems much easier to pronounce by comparison. The indigenous language competes with the colonial, and it is clear that something is in danger of being lost. As if the cultural encounter, or its impossibility, is not happening only through bodies but also, and above all, through language.

Meanwhile, at Berliner Festspiele, Mette Ingvartsen investigates in Skatepark possible connections between the language of the skatepark and that of contemporary dance. The stage is equipped with wooden slopes and ramps, where first a number of Berlin skaters perform their tricks, later joined by professionals. Many aspects of skate culture are performed: the gathering of friends for battles, the entrance of the breakers with handstands, the evenings in the park with punk/post-punk music etc. Almost a “student’s guide to skate culture”. Both amateurs and professionals emanate a great energy and sense of joy, and the audience warmly embraces the whole performance. However, I could only pick out two moments where the choreography succeeded in a clear choreographic investigation through skateboarding. The first, when a group of skaters traced specific lines on the track to the rhythm of the music and the second, when a couple of performers used theatrical masks on stage, sad, grotesque harlequins.

In light of ongoing theoretical discussions regarding decolonising the gaze, I am not sure whether this piece is a true search for a confluence of two languages or more a preying on an existing living and active culture (skate culture) that probably does not need to be enclosed in a theatre to continue its life.

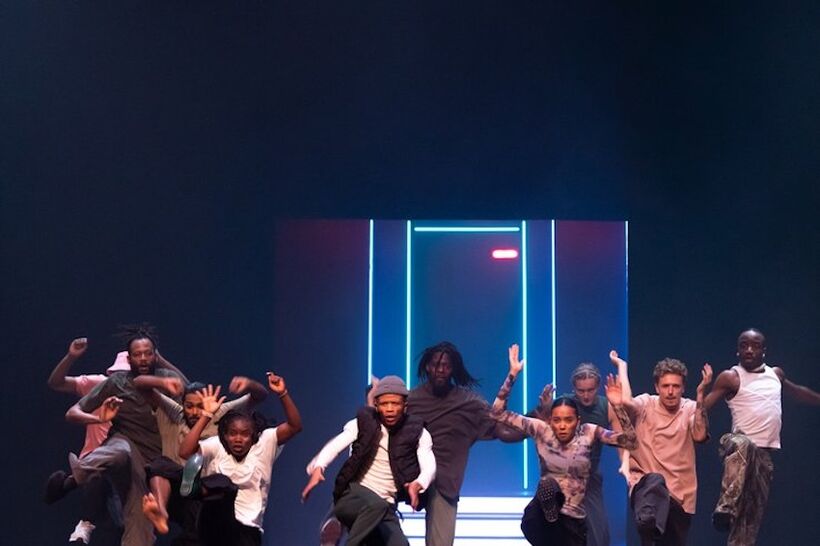

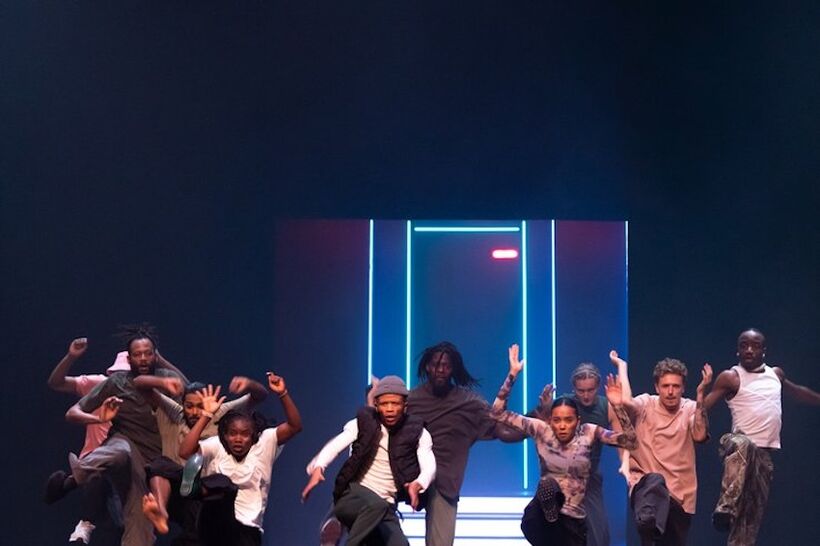

Haus der Berliner Festspiele hosts DUB by French choreographer and dancer of Senegalese origin Amala Dianor, in which diverse artistic traditions and urban styles are confronted by eleven performers from around the world, accompanied by Awir Leon’s live music. The set design is initially reminiscent of a club-like entrance, only to unravel into a multi-storey, multi-sector construction, similar to the composition of a Jamaican sound system.

Following a common practice of hip-hop culture and social media networks such as TikTok, where people learn dances from each other, the performers start in groups, amalgamating the various styles like Breaking, Voguing, Waacking, Electro, and Dancehall. After entering the construction, each of them takes a specific space maintaining his/her individual dance style.

While the piece celebrates the pure joy of sharing through movement, the genres immediately become confused which makes it hard to follow. However, this appears to be a necessary step to highlight different, hybrid dance languages, and their interpretations. There is no “pure” style, since every cultural movement form is always composed of pre-existing elements.

Trends in Reiteration

Reiteration, the repetition of a predetermined set of movements, following different patterns or scores, is a trend in contemporary dance that has been around at least since Accumulation (1971) by Trisha Brown.

In this vein, but with a current scenic and narrative apparatus, we have Mycelium by Christos Papadopoulos, created for the Ballet de l'Opéra de Lyon and making its German debut at the Haus der Berliner Festspiele. Dedicated to the vegetative apparatus of mushrooms, from which it takes its rhythms and propagative structures, the choreography features a compact group of performers who move from solos to duets until they become groups or almost a single entity of movement, like flocks of birds or waves of the sea. In this choreography of horizontality, where the dancers maintain almost the same level and focus on the audience throughout the piece, Papadopoulos’ choice is clear: to enter the infinitely repetitive. Both the process and its result are fascinating.

Presented in the Sophiensaele Festsaal, performer Viktor Szeri in Fatigue also relies heavily on repetition, this time without any kind of acceleration, build-up, or change. Just one repetitive movement that sways from right to left, a shifting of weight and a subsequent swaying of the arms. In contrast to this immanence, lights and video develop an almost disturbing visual narrative, which is projected both onto his body and the white background. Definitely a dance artist to follow for his dense scenic being, but this piece feels as if I were reading the same word over and over again.

The five-hour durational performance DREAM by Alessandro Sciarroni (Golden Lion at the 2019 Venice Biennale) instead develops a repetition of a state, of a specific presence and gestures: that of dreaming and enchantment, and, at the same time, that of coming out of it. The programme reads, “a humanity that has voluntarily chosen to become extinct, that is the imaginary scene of DREAM, a durational performance.” This is represented by six performers who are caught up in a dreamy, almost sleepwalking state, and by maintaining it, they succeed in materially occupying the space – beautiful in the brightly lit Elisabethkirche – and at times they seek contact with the audience. They look like moving sculptures: slow movements of the hands and arms, controlled twists of the torso, slow changes of level. Their gazes are glazed, between absent and inwardly directed. They are accompanied by a pianist playing classical music (Bach, Satie). With each hour, this is interrupted by a signal upon which the performers “wake up”, walk towards the centre of the hall, and sing in unison. It seems like a moment of relaxation, of togetherness, of exchanging knowing looks, before returning attentively to their inner journeys. And this is perhaps the problem with this piece: the performers are turned inwards most of the time, while the audience remains on the outside, observing, even if sometimes there is a delicate search for interaction between the two. On a theoretical level, this works: the piece recreates the “intermediate realm between music, theatre, and dance, in which everyone is invited to wander and discover new scenes”, but physically, there is a feeling of slightly too much fiction.

Memories, Bodies, and Senses

In another performative and immersive installation, Ausland by Jefta van Dinther, nine dancers inhabit the ground floor of the Kraftwerk for almost three hours, a giant, concrete industrial monument. “In a search for alternate realities”, the three hours of performance are filled with group movement explorations between somatic movement practice and a sensual celebration, solos with a Segway and robot vacuum cleaner, video installations, and songs in different scenes and zones. This dramaturgy requires the audience to move in the space, while Billy Bultheel's music maintains a constant state of delicate listening and alertness that is required of both performers and audience. Therefore, while the performance is to be enjoyed freely, in reality it is pleasantly difficult to let go and even to leave certain scenes that are filled with an intriguing intensity.

Inspired by the nuraghe — Sardinian ancient ruins, Meg Stuart & Francisco Camacho’s steal you for a moment embarks on a journey through their artistic history and lifelong friendship. They explore them both through spoken narratives, gestures, and shifts in an impressive set design. The entire stage floor of Radialsystem is occupied with pieces of wood of various shapes, sand, coloured lines traced with scotch tape on the floor, and reeds hanging from the backdrop. It is not only the two performers who manoeuvre the scene: from time to time, the set designer himself enters to modify the set, as if to accompany the duo’s story.

At one point Stuart picks up a handful of sand from the newly constructed pyramid and says “I steal you for a moment”: as she does so, the pyramid ironically crumbles and she can't really hold all the sand in her hands. A decisive metaphor about the past, theirs but also ours – the viewer's –– that can never really be kept.

The first half-hour, which certainly serves to create a certain tension, runs the risk of being a little long and difficult for the viewer to get through. However, the interweaving of emotions that are drawn out in gestures and repetitions, and the dramaturgical development between memories, dispersed and recomposed convincingly, transports us to the end. Both a moving and energising piece at the same time. The choreography becomes a living map of an individual life journey, a tool for reading and opening up.

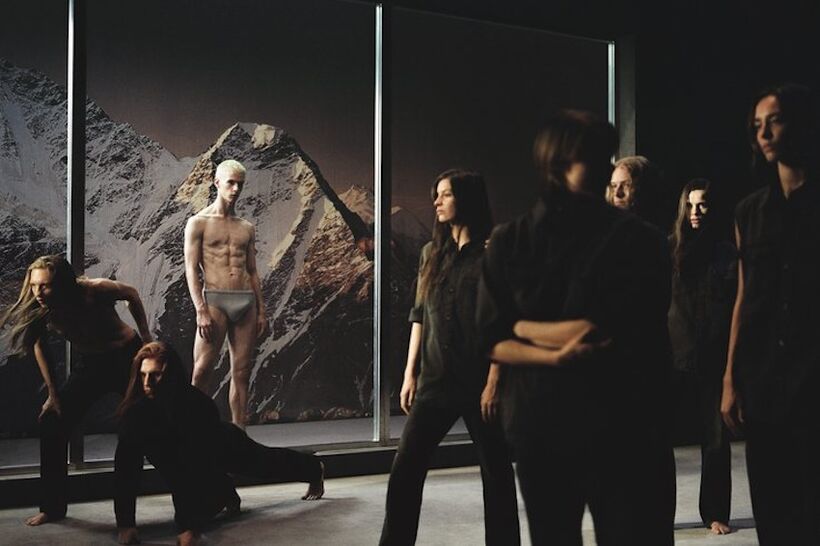

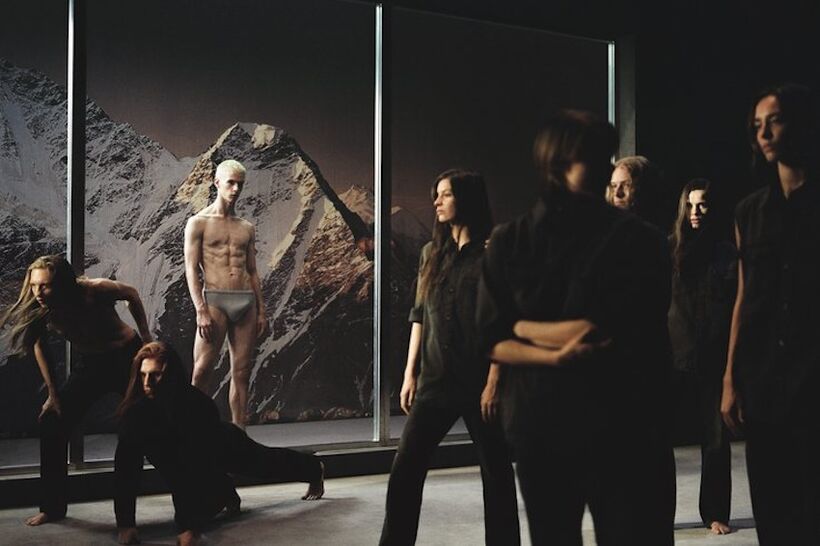

In Mont Ventoux, Madrid-based Italian choreographers Antonio de Rosa and Mattia Russo (Kor'sia) are inspired by the poet Francesco Petrarcha’s climbing of Mont Ventoux (1336). The ascent is a metaphor and stratagem for the need to find oneself, facing impervious paths. The transparent screen positioned in the middle of the Volksbühne stage is a key dramaturgical element: what happens behind is like a reflection of a life before and a life after. Naturally, Kor’sia creates epic scenes thanks to breathless duets and group movements with highly technical holds and passages, the relentless techno music designed by Alejandro Da Rocha and Raquel Tort Vázquez, all accompanied by strobe lights, smoke machines, and wind effects. However, in the movement vocabulary used, you can certainly sense the clear influence of some well-known contemporary dance languages, for instance that of Wim Vandekeybus, used more softly in this case. Yet another example of how dance never ceases to transform, steal itself, and regenerate.

In a city context where, for example, on the way home from a performance, one may come across dozens of police officers, choreographically positioned to preside over a peaceful demonstration against the ongoing Israeli massacre in Palestine, situations like Tanz im August remind us to remain human. Beyond any do-gooder discourse, by advocating for hybridity, confrontation, proximity, the capacity of choreography to act offers a remarkable example of the other realities that may be possible.

Written from Tanz Im August, 15 to 31 August 2024, in Berlin, Germany.