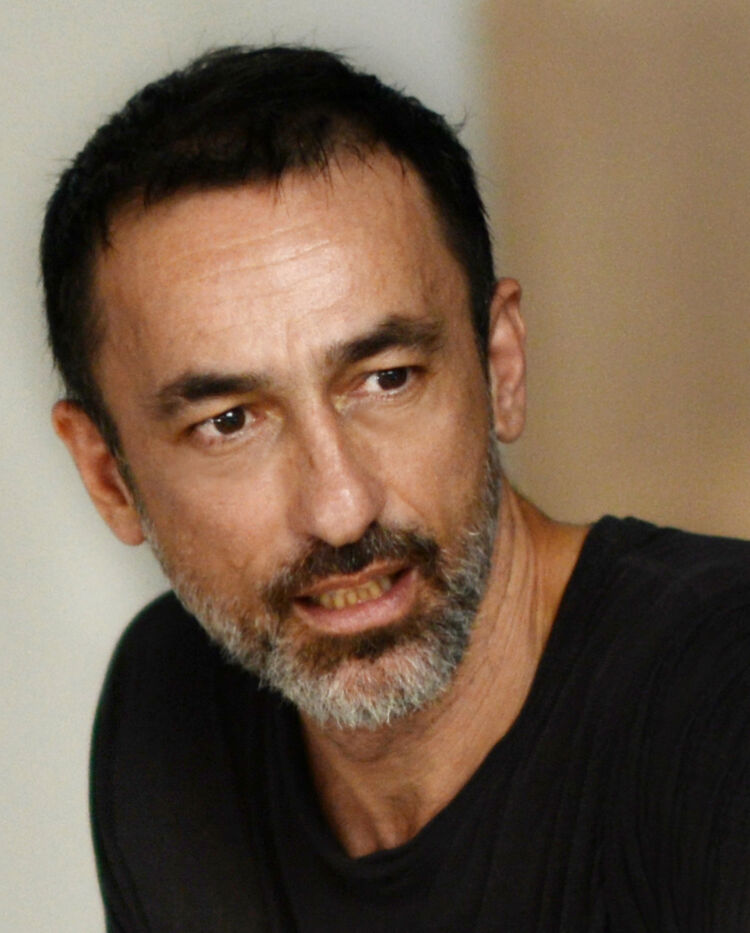

Dimitris Papaioannou: Portrait of a Creative Maverick at Sixty

Renowned as a choreographer, director, performer and visual artist, Dimitris Papaioannou wears many hats but is hesitant to label himself. He especially shies away from the term “choreographer”. Yet dance is a field that has embraced the hybrid creator for decades, while talented movers the world over audition to perform with him. Having progressively gravitated towards the dance stage, Papaioannou merges his innate sense of movement and theatre with evocative visual landscapes. From creating the opening ceremony of the Athens Olympics in 2004 to the first new work for Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal after its founding choreographer’s death, Papaioannou is celebrated in both his native Greece and around the world. On the occasion of the artist’s 60th birthday, this portrait revisits Papaioannou’s creative beginnings and a handful of his many milestones thus far.

Interdisciplinary Aspirations

In an interview about his performance Ink (2020), Papaioannou reminds audiences of his visual arts background, “I’m primarily a painter…I try to compose images”. Born in Athens in 1964, the self-professed introvert recalls a childhood filled with magic markers and sketching. In addition to the goal of painting professionally, the young Papaioannou also dreamed of becoming a ballet dancer and a movie star. Due to his drawing skills, Papaioannou initially pursued visual art studies under the tutelage of celebrated painter Yannis Tsarouchis before enrolling at the Athens School of Fine Arts. His work from the early 1980s is bold and full of gestural strokes that outline the human body, movement that can be traced across paper and canvas in graphite or tempera.

Success as a painter and illustrator came easily, but it didn’t take long for Papaioannou to expand his interest in the body beyond two-dimensional artworks. While still a student, he began exploring dance and experimented as a make-up artist costume and set designer for Greek dance troupes, all of which gave Papaioannou a taste of the collaborative possibilities within the performing arts. After discovering Erik Hawkins’ technique and Butoh during a brief sojourn in New York, Papaioannou affirms that the physicality of dance helped satisfy his emotional and intellectual needs while relieving the isolation of painting. He founded Edafos Dance Theatre in 1986, presenting a duo that same year with Angeliki Stellatou entitled The Mountain. For seventeen years, the company would offer a home to Papaioannou’s visual and choreographic explorations on stage, reflecting influences as varied as the Bauhaus, Magritte, Pedro Almodóvar, Anne Carson, and Jacques Tati.

Edafos Dance Theatre

Papaioannou characterises this early period of his career as anarchic and punk. While access to video of his first four performances is rare, short excerpts transmit an abundance of raw energy via intimate formats. Duos or trios fling themselves to the ground with brute force or swiftly chase one another, leaping across stage sets in hot pursuit. Undeniably powerful, these striking images nonetheless unfolded on a smaller scale than that which the artist would later become known for. Invitations in 1987 and again in 1988 to the Biennale of Young Artists from Europe and the Mediterranean bestowed an important form of institutional recognition on Edafos Dance Theatre from the outset. Despite the company’s successful reception, Papaioannou’s interdisciplinary interests briefly led him away from Athens after approaching acclaimed theatre director Robert Wilson in 1989. Wilson offered Papaioannou a position as his assistant trainee in Hamburg for The Black Rider: The Casting of the Magic Bullets, a contemporary opera co-created by Wilson, Tom Waits and Willam S. Burroughs. Afterwards, Papaioannou’s followed Wilson to Berlin, where he became a lighting stand-in for the director’s production of Orlando.

Drawing on his experiences in Germany and a side project in Boston, Papaioannou returned to Athens in 1990 rejuvenated and set out to make The Last Song of Richard Strauss, a dance theatre performance that unfolds in slow motion. Kindling a growing underground dance scene in Athens, the artist was astounded by public response to his interdisciplinary performance, which toured nationally. As he recalls, “I had found my territory. As a painter, this was the place to create images; as a comics artist, this was where to tell my tales; and as a performer, this was the context in which to present myself.”

Ancient Greek Heritage

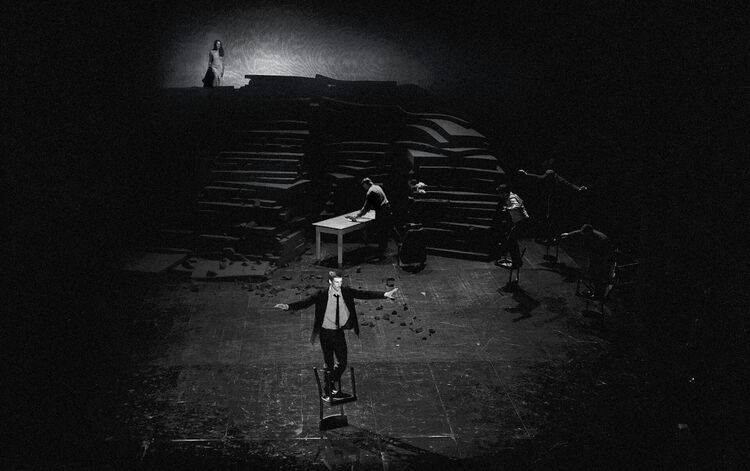

While Papaioannou’s creative influences are varied and international, he regularly refers to returning to his own heritage of Greek myths as key. The 1993 performance Medea marked an important turning point for Papaioannou and Edafos Dance Theatre. With its 5 performers and elaborate set design, Medea established a large-scale theatrical context for Papaioannou’s work that saw the company transition from a popular artist’s squat to the 700-seat Greek National Theatre. The dancers’ white painted bodies, gnarled hands and curved torsos merged the aesthetics of Butoh with Papioannou’s own costume designs and punk spirit. The artist’s predilection for the use of water on stage is seen throughout the one-hour-long performance, an element that, as Papaioannou asserts, transforms everything, from light to skin. A Greco-Belgian co-production, Medea has been performed 52 times and seen in multiple countries, including a performance attended by Pina Bausch. As its title indicates, Medea revisits Euripides’ vengeful tragedy of infanticide. For Papaioannou, myths are accessible through their storytelling, with powerful characters presented as archetypes, a source the choreographer has revisited throughout his career.

Although he is quick to assert that he is not bound to a faithful retelling of myths, Papaioannou is inspired by how Greek myths sit within a wider international context, allowing artists and audiences to interface with important archetypes. In 1995, the success of Medea led to Papaioannou’s even larger scale Xenakis’ Oresteia: The Aeschylus Suite, that reimagined the Oresteia trilogy for 13 dancers, 28 climbers and over 100 musicians at the ancient Epidaurus Theatre. Immersed in water tanks, scaling walls, or dropping from ropes, performers were once again painted in white, channelling fantasy states beyond realism. Papaioannou cites ancient Greek theatre, another local source of inspiration, as a “psychotherapy for society” to “process loss and existence”.

The Olympic Games in Athens

In 2001 Papaioannou was invited to become Artistic Director of the opening and closing ceremonies of the summer 2004 Olympics in Athens. This was a transitional period for the artist, during which Edafos Dance Theatre had nearly folded and Papaioannou stopped performing but began directing operas and collaborating with the Greek National Theatre. Following a rocky start with the Olympic organising committee, Papaioannou created Birthplace, an opening ceremony for 2,428 volunteer performers. Taking a sensual approach to Greek identity and art history, vertical dancers costumed as Apollo and Cupid seamlessly treaded air, while other performers embodied athletic statues of antiquity. Chariot drivers held raised arms in profile, as a steady stream of historic images came to life amid a colourful parade of nations.

For the closing ceremony on 29 August, Papaioannou shifted his focus from Apollonian ideals to those of Dionysus in a tribute to the agricultural links between folk music and dance. Hundreds of wheat-bearing amateur performers created a giant moving spiral, circling in procession of renewal and joy. Often hailed for their memorable opening and closing ceremonies, the Athens Olympics provided Papaioannou’s work with mainstream visibility around the world. The artist, nonetheless, looks back on that time with mixed feelings, having navigated the labyrinthian politics of both local and international interests. Despite his objections to the Olympic organisers’ insistence that a performance must be “logically understood rather than emotionally experienced”, Papaioannou infused the opening and closing ceremonies with his trademark interdisciplinarity, creating a sensorial odyssey for television and stadium viewers alike.

International Acclaim

Papaioannou’s didn’t lose any steam following the Olympic Games. Creating the performance 2 (2006) that played to sold-out crowds in Greece, he continued to mine Hellenic culture in Homer’s Iliad Book Four (2010) and Still Life (2014), experimented with a six-hour performance installation format for Inside (2011) , and even returned to the stage briefly as a performer in Primal Matter (2012), which embraced a more minimalist sensibility.

The year 2014 marked yet another milestone in Papaioannou’s upward trajectory with growing international interest in his work. “Other countries discovered me”, he says, and the whirlwind touring schedule to elite international institutions, including France’s Festival d’Avignon and the Hong Kong Arts Festival, has not slowed since. But it was Tanztheater Wuppertal’s request to create a new work for their dancers that earned Papaioannou unequivocal clout in the dance world. Following Bausch’s death, the German troupe had continued to restage her performances for nearly a decade without inviting any other choreographers. The obvious sympathies between Bausch and Papaioannou’s expressionist dance theatre made the latter a natural candidate for collaborating with the company, though his production methods rely much more on visual cues than they do Bausch’s use of language. Since She (2018) became a surreal series of sombre tableaux that frame improbable anatomies, including a woman’s head that emerges atop a nude male torso, while long tubes extend like stilts from the arms of another dancer. These illusions are produced through imaginative partnering and costumes, framing visual composites that are both unsettling and wondrous.

The Art Life

From creating intimate duos to Olympic ceremonies for performers that number in the thousands, what is Papaioannou’s artistic process? His reticence to denote starting points or to interpret his work stems from a respect for emotional intuition when it comes to the subjects and people he finds interesting. He admits to bringing a chaotic process to the studio, arriving at times with seeds of ideas about materials or topics that he prefers to experiment with in a laboratory setting. Despite the financial investment it requires, Papaioannou insists on longer periods of artistic preparation and rehearsals, which he deems a necessity.

As for dancer auditions, Papaioannou attempts to surround himself with individuals who intrigue him. “Of course, they must move well”, he adds. He readily cites dancers as integral during the choreographic process, including the ways their personalities may contribute to a work. The same goes for additional artistic collaborators, who include sound designers and composers. For Papaioannou, music is vital to setting the mood for a piece and creating a dialogue with the performers, as well as the other layers of production.

Addressing this interdisciplinarity more broadly, he notes the overlap of one element over the other until reaching the perfect assembly. And this perfection can emerge out of the strangest circumstances. Currently touring internationally, Ink (2020) was created during the early days of the Coronavirus lock down and Papaioannou has returned to the stage for the occasion. It’s a rare opportunity to discover yet another aspect of Papaioannou’s multifaceted career during the artist’s 60th turn around the sun.