Biennale Danza 2024 — We Humans (and We Dancers)

In the hot month of July, the 2024 Biennale Danza festival edition entitled ‘We Humans’ sought to give space to human beings’ need to communicate through movement. Curated for the fourth year by British choreographer Sir Wayne McGregor — recently reconfirmed for the next two years — a vast and inclusive theme chosen to encompass different genres and backgrounds. The festival masterfully brought seven world premieres, two European premieres, twelve Italian premieres, visual and durational installations, an exhibition, and a smart catalogue to the Venetian lagoon.

In the catalogue opening, McGregor writes “For thousands of years, We Humans have communicated by moving.” He thus seems to be aiming straight at the communicative power of dance and bodies in movement. This, in my opinion, and at least in the performances I saw, worked very well.

Golden Lioness Cristina Caprioli

Each year, the festival hands out two of its iconic Lion prizes. This year, the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement went to Italian Swedish choreographer Cristina Caprioli, and the Silver Lion, dedicated to the most cutting-edge figures in dance in recent years, to American Trajal Harrell.

Born and raised in Italy by an Italian father and a Swedish mother, daughter of art, Caprioli trained between Italy and Sweden, where she founded ccap in 1998 (first the “Cristina Caprioli Artificial Project”, later “Crash Choreography Alliterative Periphery”). In the outskirts of Stockholm, she curates The Hall, offering free performances for audiences of all ages and backgrounds.

McGregor traces Caprioli's journey as “a dancer, a choreographer, a teacher, a writer, an academic, and a curator (...)” with an “innovative and boundary pushing body of work”. For three decades, her “powerful and compelling work has quietly and substantially influenced multiple generations of choreographers”. Caprioli’s interdisciplinary work, imbued with a physical intelligence and made up of performances, installations, writings, and theoretical encounters, reveals a precise and complex “highly accessible embodied experience”.

Being awarded the Golden Lion is reward for Caprioli’s subtle, continuous, and multidisciplinary research that is both cogent and meaningful. At the same time, it may be a somewhat “strange” choice within Italy. Whilst abroad, especially in the Nordic countries, Caprioli's work is well known (for example the beautiful retrospective proposed at the 2022 Berlin festival Tanz im August), in Italy she is still lesser known due to the scarcity with which her work has been shown. However, it is worth mentioning Caprioli's presence as a tutor in the ‘WORKSPACE RICERCA X - RESEARCH AND DRAMATURGY’ programme (curated by StandOrt Performing Arts, supported by Fondazione Piemonte dal Vivo at Lavanderia a Vapore), and we hope to get to know her work better in the future.

In Caprioli's own emotional words at the award ceremony, in addition to her immense gratitude, she mentioned a word and a conscious reflection: “privilege”. In heartily receiving the Lion, Caprioli understands that on this occasion she does not have to defend her work (and in this sense is a privilege). At the same time “comfort is incompatible with the work” and that as “each move has its own evidence”, it must instead be constantly defended.

Caprioli presented four choreographies and installations at the festival. The Bench (2024, presented as the “first informal performance of a project in the making”) was performed by the Biennale College dancers. With the backdrop of the tree-lined Viale Giuseppe Garibaldi Avenue, in front of the Serra dei Giardini greenhouse and café, the young performers’ dance seems to stop time and offer relief from the scorching mid-afternoon heat. Dressed in black and white, the dancers inhabit the avenue with minimal movements, oscillating between the everyday and the refined, including walking and running, until they develop duets and trios with the red benches situated along the avenue. A dance that carries with it a sense of waiting, of lingering, almost, as the dancers gently kick up the avenue dust.

Deadlock (2023) is a multidimensional piece featuring dancer Louise Dahl that appears as a video installation and then as a solo. The Teatro alle Tese is transformed into multiple large, wave-shaped screens, where the dancer is initially projected in motion, before appearing live and in dialogue with them. In this very dark environment, the dancer is dressed in a silver and light blue jumpsuit and is in release, with dynamic tours and wide movements to occupy the space.

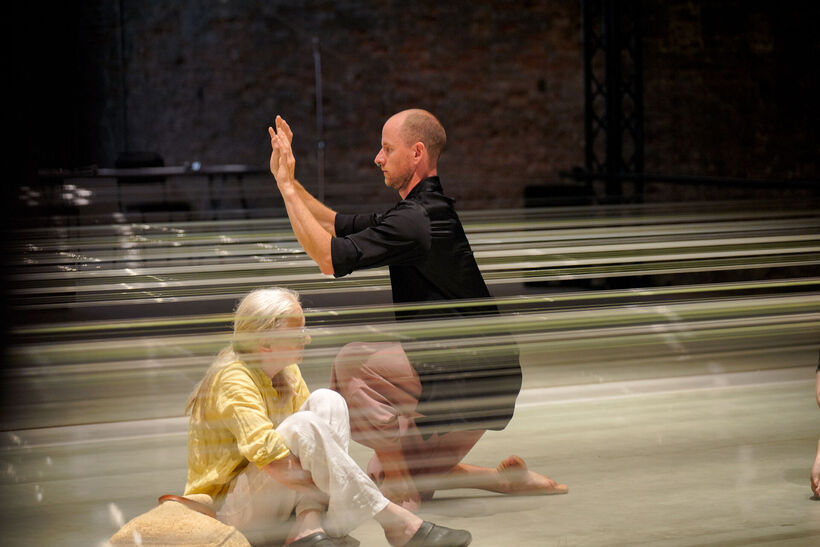

The durational, nine-hour-long performance flat haze (2019), set in the beautiful Sala d'Armi E, captivates me. The time, the coolness, the glacial soundscape of American composer Richard Chartier, the being with the dancers for an indefinite time and welcoming anyone who passes by and wants to come in. flat haze is a reflection on the characteristics of a space for thinking and for dancing, which, according to Caprioli, “must be isolated, not excessively lit and inhabited by uniform white noise”.

The space is divided by two levels of (probably plastic, nylon-like) taut cables, where mostly solos, duets, and trios follow one another, sometimes accompanied by fans. In the eyes of the beholder, the dance is never invasive or grabbing, but the bodies and movements come to us just like a “light haze”. It is an absolutely regenerative experience for body and spirit as it leaves that individual time of reception, without entering into the classical logic of performance consumption, where the space-time offering is delimited for a ready-made end product.

The installation Silver (2022), on the other hand, is presented in Forte Marghera (Mestre). It is a participatory performance of about forty minutes, a dance “of bodies without bodies”, created by hundreds of silver rain jackets inhabited by both humans and the surrounding environment, as they are placed on trees, parts of the wall, etc. However, while it succeeds in its intention of being a “visual reflection”, pleasant, tender, material, this attempt to only bring Silver to Mestre seemed to me more like a colonisation of Mestre than a real opening of the festival towards the hinterland. Here, I am obviously not talking about Caprioli's choice but about the Biennale’s curatorship. I think it would have worked better in the context of a richer programme in Mestre, a city that, thanks to the work of some local associations (such as Live Arts Cultures) in raising awareness of contemporary art, is certainly ready to welcome more structured choreographic pieces.

The Silver Lion Trajal Harrell: “We smile as quickly as we cry, as in a roller coaster”

Choreographer and dancer Trajal Harrell is this year's Silver Lion. In McGregor's words, Harrell is a “true original”. With a foundational discourse based on post-modern dance, voguing, and Butoh Harrell, has investigated “gender, feminism, and post-colonialism” in fashion pop culture and avant-garde movements, creating a sensitive and hybrid genre.

In Sister or He Buried the Body (2022), Harrell researches the work of Tatsumi Hijikata, one of the founders of Butoh, and connects it with Afro-American choreographer Kathrine Dunham, who seems to have shared Hijikata's studio in Tokyo for a while. In Harrell's stylistic approach, we thus find research on the body as a geographical and collective memory, using a movement language influenced by vogueing, Butoh, and contemporary dance.

Dressed initially in a long skirt, Harrell dances seated on a stool almost the entire time, creating ports de bras and undulating movements of the torso. His stage is a very confined rectangular space, bounded by four ropes and fabric on the floor. Only for a few brief minutes at the end does he get up, taking off his skirt and remaining only in a black T-shirt and black shorts where the words “no pain, no gain” are clearly visible. It is this tiny yet incisive inscription that brings us back, not without a lightness of heart, to reality.

In the post-show meeting with the audience, Harrell explains that the piece is a reflection on what it means to dance as one grows older, a performance for when time is running out. Harrell then almost creates a movement will & testament: a dance that he will be able to perform even when he is seventy years old. A refined piece, undoubtedly moving without ever being cloying, where it seemed to me that the choreographer, confronting the movement archive of Hijikata and Dunham, was searching for a future self. I wonder, however, if I had not read the specific context written in the presentation and heard his words in the audience meeting, to what extent would I have appreciated the performance itself?

Dancing with bodies and from inside them

Natural Order of Things by GN|MC Guy Nader|Maria Campos is performed by nine dancers to minimalist music by Coti K. In the choreography, the figure of physical partnering becomes dominant, at times almost acrobatic but never purely gymnastic, always demonstrating an attentive and receptive listening to the other. A work capable of leading the audience into extreme physicality, into moving bodies where the measure of any gesture is calibrated to the millimetre. Mesmerising.

If in the Natural Order of Things everything is already on stage, on sight, in a “naked and raw” dance, in Waves by Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, a decisive role is played by technology in the hands of digital artist Daito Manabe. The music, as well as the images, are AI-generated, using sensors that signal the dancers' movements. The choreographic language is a continuous flow of takes, solos, duets, and group movements which, despite a few moments of total immersion between dance, screen, and sound, feels repetitive as the performance goes on, without any real dramaturgical twist.

In De Humani Corporis Fabrica (2022) by Verena Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor, we see bodies from the inside. A corporeal installation on several screens simultaneously. Here the choice of shots is striking — blood, organs, surgical instruments, probes navigating inside the body. Between an operating theatre, horror film, and video art, we explore inside that which makes us move.

Looking for new generative steps — we want (and need) more

The festival programme also features the Iconoclasts exhibition. Donne che Infrangono le Regole alla Biennale Danza (Women Breaking the Rules at the Dance Biennale) curated by McGregor with Italian dance critic Elisa Guzzo Vaccarino and the Archivio Storico delle Arti Contemporanee (ASAC), which is striking for its specific photo selection. However, these photos are often copied and not even of great quality, and the exhibition as a whole remains poor in terms of its real structure, displaying beautiful photos and little content. Furthermore, I wonder if in 2024 there is still a need to define female choreographers as “iconoclasts”. If the exhibition had been dedicated to male dance artists, would they have been called that? On the other hand, the catalogue is a very valuable tool.

In the catalogue, which contains, among others, interviews with the two current Lions, the festival’s first director Carolyn Carlson, and Claudia Rankine's essay, we can find out more about the political figures of this year’s Biennale Danza. Beginning with the Tang ping movement (Tang ping means choosing to ‘‘lie down flat and get over the beatings’’ via a low-desire, more indifferent attitude towards life), Rankine speaks of bodies at war, today and always, where we humans are inhuman. In her appeal that “We Humans must let our movements be our State becoming human”, I find another layer to this biennale.

If on the level of international calls, the festival hits again the mark, bringing important shows to the lagoon, once again there is almost no voice for Italian dance. I can understand the curatorial choice, which favours certain performances with an international scope and which, perhaps, can distance themselves from the Italian perspective, where we often hear “the usual names”. However, I continue to wonder what it would be like if artistic director McGregor’s specific eye and the idea of being “alert (...) truly caring and daring” — as defined by Caprioli in her speech for the Golden Lion, and with which this writer agrees — could take on the task of reflecting on Italian dance? On the other hand, the Biennale Danza remains one of the most important Italian festivals. How would it be if its efforts were also directed towards strengthening domestic work? Remember: an Italian territory linked to dance has always suffered from structural deficiencies.

Making the special choice of awarding a Golden Lion with such artistic weight, how could it create a generative push to open itself up to the Italian discourse as well? Venice in particular: a place where, despite the fact that there are a few private dance schools that promote excellence, and a rare few (but good) centres dedicated to contemporary dance, there is an almost total lack of professional dance opportunities. In this sense, the Biennale Danza represents a privilege, and my big question always is whether it will ever be possible to extend this privilege to those who live the Italian dance reality 365 days a year and not only during the festival?

Written from We Humans Biennale Danza International Festival of Contemporary Dance from 18 July to 3 August 2024, in Venice, Italy.