Intro through your skin

This year’s BDF commenced with an extravagant debut, that of Spanish choreographer Blanca Li’s virtual reality project (designed by Vincent Chazal), entitled Le Bal de Paris. In small groups of ten per session, we enter an imaginary digital world of luxurious Chanel dresses and black suits, full of vivid details. We fly, we are taken on boat and train rides, we enter a ball, and a cabaret can-can, accompanied by magical creatures à la Harry Potter or Alice in Wonderland. We explore dreamlike Italian sunsets and a secret garden hiding an entire maze within. Li erases the boundaries between reality and fiction through the impressive use of technology.

Over three acts, the two dancer-avatars, Adele and Pierre, lead the audience through their dramatic love story. However, the performance’s narrative is very simple, and the predictable plot is overshadowed by the abundance of visual and technological marvels. Instead of concentrating on the dancers and their amusing movements (they perform weird jetées, wave their hands like some kind of rare animal), the spectators are looking everywhere else in amazement.

Using VR in performance art is still a new phenomenon. Li attempts to create an immersive and participatory piece, but it does not move me except as an exploration of technological possibilities. I could not perceive a purposeful necessity for our immersion in the virtual world. As a phenomenon, it is difficult to see how the VR experience will contribute on an embodied level. In the end, even in VR our dance movements are restricted by our own ‘real world’ bodies. It was a fascinating experience, but I didn’t experience any new cognitive or empathetic realisations. Maybe I’m just old-fashioned, but I was relieved to return to reality for the rest of the festival.

Orly Portal - Fakarouni - Eli Katz.jpeg)

Exoticism always sparks interest

‘Remember me’ is the English translation of Israeli choreographer Orly Portal’s dance piece Fakarouni, referring to the homonymous tune of iconic Middle Eastern singer Umm Kulthum; her music is also at the centre of this exploration. Through this intense, undulating homage, Portal elaborates on themes of love, passion, and cruelty, celebrating women’s empowerment in a patriarchal system. In her innovative and refreshing style, the choreographer mixes belly dance with a variety of other influences, from contemporary dance to contact improvisation.

The piece starts with three men (Anderson, Estman, Zohar) on the stage, graciously flowing in dervish-like whirls, spins, and jumps, the dancers seemingly being led on the way by their hypnotic handwork, in ripples and swirls before our eyes. They keep hold of my attention, even if the section drags on for quite some time. By mixing movements from traditional folk dances in a temperamental shift of positions, they depict and mimic desperate men ‘losing their heads’ over a woman. The atmosphere changes as Portal enters the stage with her sensual movements, focused on the pelvis. The men are now her admirers. The choreography concentrates on constant human interactions, from trios to duos, the main theme being the relationship between genders. As much as Portal’s dance vocabulary fascinates and inspires, the dance remains somewhat entrapped in a run-of-the-mill diva-scheme, where from start to finish the male admires and competes for the female, without exploring any deeper aspects of that relationship. Or am I simply missing some deeper cultural signs?

Israel Galván - Le edad de oro - Felix Vazquez.jpg)

While Spain’s flamenco superstar Israel Galván is certainly no newcomer, his show La edad de oro proved immune to anachronism. The title refers to the golden age of flamenco, but Galván doesn’t try to revive the period, instead he puts his own, bold imprint on the genre. Characteristic of his work, the scenery is minimal. The emphasis is clearly on the raw body and the raw music, performed by a dancer, guitarist, and singer. It is a performance of exploration and communication expressed through genuine duende.

In an extraordinary, authentic performance, Galván furiously articulates his moves with an energy that bursts through the theatre. One is mesmerised by an incredibly intense and dense piece that invites you to meditate on bodily structures and patterns and the delicate dialogue between dancer and musicians. Abrupt shifts between rigidity and sensuality jolts us out of our hypnosis, while Galván uses his own body as a musical tool by tapping his chest forcefully and violently pulling his cheek to the side with his fingers in spasmodic vibrations. The expressiveness and fearlessness of flamenco culture is there, full of internal dynamics. Impossibly fast floor work follows the beat of the percussion, accompanied by sensuous and sometimes geometrically rigid arm positions. All the while, the dancer plays whimsically with flamenco imagery, as with the famous torero pose.

Galván shows us how to push a genre in new directions and towards the extreme. It is incredible what flamenco can be in the hands of a true pioneer.

Balletto di Toscana - Bayadere - Alice Mattiolo.jpg)

Bayadère (The Kingdom of the Shades) by Balletto di Toscana is an exploration of the famous dream scene of the classical ballet of the same name. Twelve bodies occupy the stage re-enacting the tragic love story of Solor and Nikiya. Choreographer Michele di Stefano’s vision lies in the interplay between two different corporal and auditive sensibilities. The music oscillates between the original score by Ludwig Minkus and experimental music by Lorenzo Bianchi Hoesch, while sudden, disturbing roars and aquatic sounds complete the soundscape, evoking the sound of rainfall. The dancers constantly refer to the original choreography – the arabesques, tendus, en croisés and cambrés, posé à terre – performed with astonishing synchronicity, at the same time rigid yet soft. But this well-known sequence is combined with movements resembling martial arts or even ice skating: jumps, spins, quick and frenetic handwork that seem to leave traces in the air, a recurring reclining pose, as in Manet’s Olympia. Sometimes their gestures become sharp twinges of their hands and heads. With their occasional smiles and teasing looks towards the audience, one senses that there lies a subtle irony, verging on satire, hidden beneath the classical references.

As the ending approaches, the Bayadère vanishes on the other side of a veil draped over the stage. Their final unison is therefore almost hidden, we can just about glimpse the dancers moving together towards eternity - as the curtain falls we are jolted back to reality like Solor from his dream.

Euripides Laskaridis - Elenit -Julian Mommert.jpg)

In alienation there is still hope

In Elenit, the fantasy world of Euripides Laskaridis vibrates disturbingly through our veins. Like a Dylan Dog of dance-theatre, Laskaridis is challenging any conventional definitions. He puts his very own vision on stage: creatures and images of profound absurdity. What do they become once they are put on stage? And will they provoke our curiosity?

This surrealist weirdness challenges the audience to reflect. We are confronted with a confusing chaos in search of meaning, while it all remains open to individual interpretation. There are ten characters in total. The protagonist, a diva-sorcerer (picture Marie-Antoinette going goth) with the hoarse cough of a smoker, curiously shrinking through the performance while roaming extravagantly across the stage in her fluffy dress, is interpreted by Euripides himself. Other characters remind us of figures from popular culture, such as the bald man from The Addams Family, or Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz (here, she suffers from narcolepsy). On the stage, Mona Lisa mixes with the sculpture of Niké under rave-like strobe lights. In the background, strange sounds crawl towards us without any clear meaning: screams, a voice singing, then indecipherable mumbling, and at one point, something resembling a rave-metal fusion. But while this might all seem ‘a bit much’, the performance is saved by a permeating sense of humour. The piece does not take itself too seriously. It’s a Rabelaisian carnival mixed with meta-theatre. The raw physical expression and energy that fluctuates between the performers and the audience encourages us to celebrate life as a ridiculous feast.

Leaving the theatre, I can only recall Shakespeare’s idea of life being an absurd comedy; ‘a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing’. And still, in that ‘nothing’, we tend to find some meaning.

Balletto di Torino - Faun - Andrea Macchia.jpg)

Towards the end of the festival, Balletto di Torino arrived with the premère of their piece Faun by Mauro de Candia. Referring to the famous poem, Après midi d’un faun by Mallarmé, this Italian Faun takes a very different shape and direction.

Four dancers are on stage, all in gold, with lights pointed at them from both sides. The interplay of colours continues throughout the piece, making it a journey of the palette: from golden to black and turquoise, returning in the end to gold. Electronic tunes vibrate in the background, occasionally interrupted by rustling, crackling, and string instruments. We’re exploring the idea of this mythical creature, the Faun. In common imagery it evokes raw masculine energy and power. However, these fauns’ movements explore other qualities, as the dancers search for different identities between the human and savage impulses of the creature: from slow gnawing movements, where everybody curls up together and around each other in the shape of a ball, to the rigid, grotesque positions of arms and bodies entrapped in hospital bandages. The typical virile masculinity of the creature appears only once, when the dancers come together to form a creature that (ironically) looks more like a centaur than a faun: flexing its biceps, the creature proudly expresses its virility.

While the languid intentionality of the choreography is fascinating, I leave feeling that something is missing in this piece. It was also hard not to notice the less than enthusiastic applause. Was it because the interpretation is too much of an inward vision that it did not hit home with the audience? Or is it simply the slowness of the movements that dream us away, and like the dancers, in the end we are lullabied into the darkness of an empty stage?

Sharon Eyal - Promise - Andreas Etter.jpg)

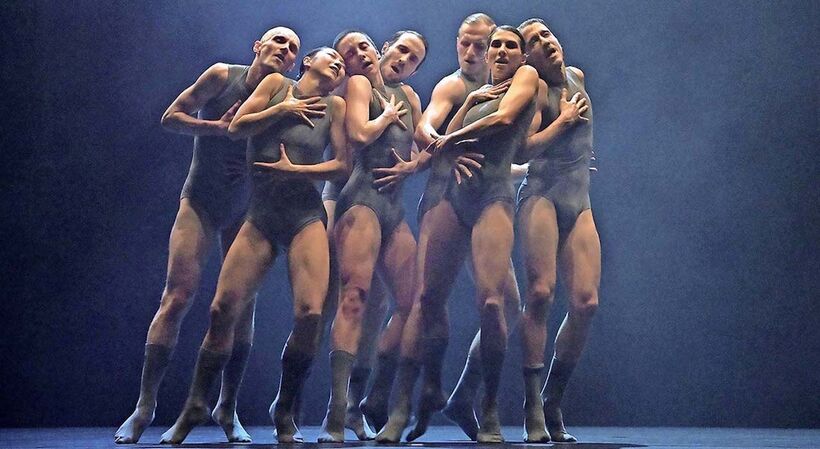

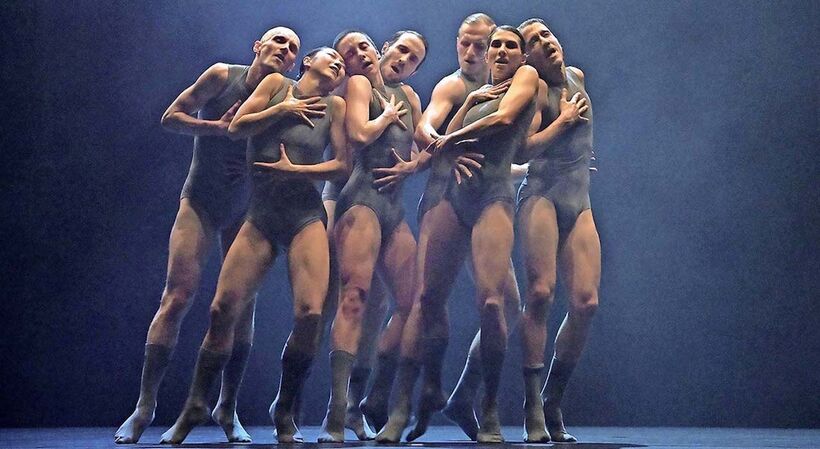

Sharon Eyal’s Promise performed by TanzMainz was the last dance on my itinerary. If the Italian faun lets us dream away, Eyal shakes us violently back to the present. Lasting only fifty minutes, the performance leaves no time to relax. It’s tense, dense, and devastating (in a positive way). Dancers enter the stage in a rigid upright posture, dressed in simple, pale blue leotards and long socks. The lights change constantly, from a circle to a rectangle. The dancers shape themselves accordingly. A feature for which Eyal is already well known is the combination of techno music and a group of dancers that seem to be part of one whole, one many-footed and many-armed body.

The performance is compulsive, ecstatic, with ritualistic tendencies. The dancers obsessively repeat some of the gestures and footwork: touching their shoulders (from left to right), their mouths, and reaching for the sky. They pulsate together, breathing heavily while releasing their shoulders, forming some kind of a pore structure. They step, walk, or run, sometimes half sometimes full en pointe. The physical demands are palpable. Many images flush before our eyes: a head isolated from the others on the back of the body; one dancer suddenly sucked inside a heart-shaped form; head twitching and so on. The hip movements reminded us of chickens (although this might have just been me!). The humoristic elements, however, only added to the charm.

The vibrations of the dancers’ bodies evidently affected the audience as well, as their applause was the longest I experienced at this festival. The next day I caught myself whistling one of the tunes. Like the performers of the play, I looked up at the sky. I thought about how Dante ended each of his canticles with the word ‘star’, as a symbol of guidance, hope, or rather some kind of promise of better times…

Written from the Belgrade Dance Festival, from 8th March to 13st of April, 2023, in Belgrade and Novi Sad, Serbia.

Orly Portal - Fakarouni - Eli Katz.jpeg)

Israel Galván - Le edad de oro - Felix Vazquez.jpg)

Balletto di Toscana - Bayadere - Alice Mattiolo.jpg)

Euripides Laskaridis - Elenit -Julian Mommert.jpg)

Balletto di Torino - Faun - Andrea Macchia.jpg)

Sharon Eyal - Promise - Andreas Etter.jpg)