A Canadian Evening at Sadler’s Wells, ruled by Crystal Pite

After more than 10 years, the National Ballet of Canada came back to London with a truly national programme consisting of three Canadian choreographers of different generations – James Kudelka, Emma Portner, and Crystal Pite.

The programme at Sadler's Wells opened with Passion, an approximately 30-minute choreography piece by the eldest of the creative generation, James Kudelka, and which was devised in 2013. On stage, he presents a strange clash of the world of classical, or rather neoclassical ballet, with its romantic tutu skirts, tiaras, female corps and men in tights (and vests with straps at the sides resembling those of lifeguards), and a more contemporary couple, perhaps of today's world, who are meant to be a kind of centrepiece of the whole performance and the vehicle for its idea, whatever it may be. Kudelka's basic premise has the potential for interesting confrontations and contrasts, but they hardly occur on stage, and the result is just an awkward affair, prompting a four-year-old child’s favourite recurring question — why?!

The main couple (Heather Ogden, McGee Maddox) are obviously, according to the costumes, meant to be representative of that real, tangible, contemporary world that is straightforward and down-to-earth, in which emotions do not have to be wrapped up in the aesthetically romanticized form of pink stockings and pointes. But of course, the ballerina is on pointe, and while her partner is dressed in a plain T-shirt and trousers, she runs around on stage in a velvet purple dress, which is far from a casual day-to-day outfit, appearing rather "costumey" and unintentionally comical. Reflecting, permeating or perhaps acting as a partner from another world to the contemporary couple is the couple consisting of prima ballerina (Genevieve Penn Nabity) and her prince (Larkin Miller, insecure in his own dancing as well as partnering) coming from that universe of shimmering tulle and ornamental female corps (and two demi-solo couples, who are presumably there only to fill out a kind of [neo]classical form). The two couples are often on stage together, but each forges their own, independent line and story, and there are no outright interactions. It is practically impossible to successfully watch both couples at the same time, the audience’s attention is splintered and, from their point of view, it is impossible to determine what is important, and the choreographer does not help much composition-wise either. It is possible that each pair is supposed to develop the same emotion, the passion proclaimed by the title, but each in their own way, within their clearly defined world and its norms, but this is not detectable or understandable from what is occurring on stage. For Kudelka does not sufficiently differentiate the dance vocabulary of the main couple detached from the "ballet context", resulting in a narrow range from neoclassical to neo-neoclassical, which is simply not enough to create the desired contrast.

If we understand the role of the choreographer in a mechanical way, Kudelka is probably a competent person capable of putting together the individual steps and motifs in time and space, but if we expect any added value from them (and it is irrelevant whether this would be the story, mood, or the simple expression of the music, and Beethoven's Piano Concerto in D would have been something to work with), in Passion, at least, the choreographer has not shown much of it.

After a very awkward first half, it was the women’s turn and, if I wanted to be fatalistic, I would say that the world has become an exponentially better place to live in. At least the theatrical one. The still very young Emma Portner’s duet islands is a subtle miniature unfolding over atmospheric planes of electronica and the tinkling sound of piano (and Lily Konigsberg's Rock and Sin, a song that somewhat stands out from the whole and about which I’m still undecided). What makes it stand out from the mainstream is the fact that it is made for neither a heteronormative nor a male couple, but for two women, which, I admit, instantly caught my attention. In the first part, Heather Ogden and Genevieve Penn Nabity merge into one, their bodies losing their own contours and melding into one another, a mirror as well as a split personality, support as well as schizophrenia. Their duet, framed by a rectangular cutout of light in an otherwise pitch-black scene, is intimate, sensitive, connected by shared experience and intertwined bodies. They are momentarily separated when the dancers drop their dark grey trousers, but at the very end, not unlike magnetic forces, they glue their foreheads together again, precisely the kind of small details that add depth and have the potential to move you somewhere deep inside, even if the piece itself may not be groundbreaking in any way.

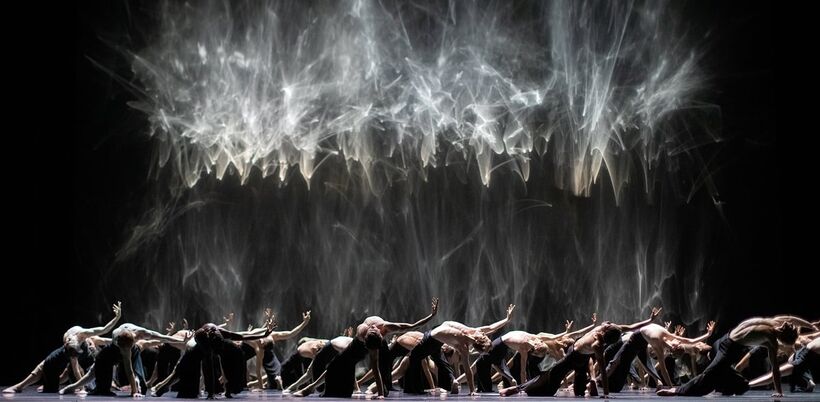

If we were to list the most important names in 21st-century choreography, Crystal Pite would be right up there, so it is only understandable that the National Ballet of Canada brought to London its most famous compatriot’s work. Pite created Angels' Atlas specifically for the company, and the piece premiered in late February 2020, just before Covid-19 brought the world to a halt, and as much as the creator could not have known about such a thing during the creative process in the studio, it adds another dimension to the choreography and heightens its urgency. Angels' Atlas falls into a group of pieces where Pite likes to make use of large ensembles of dozens of bodies, something she is very skilled at, a rarity these days. The canons spill over into pulsating unisons that break into two opposing voices, only to merge back into one the next moment. Flared dark trousers on wide-open legs in deep second positions are grounding, while exposed torsos and expressive arms trace sweeping arcs through space, reaching out, seeking, wanting, fighting. All interspersed with duets in which, despite the dynamically demanding uplifted figures and the menacingly empty-looking stage space with a massive projection screen in the background, the artist always manages to achieve the much-needed nubile, human fragility, and raw emotion that leaves no holds barred.

Angels' Atlas is wrapped in darkness, only cut through by the brilliant lighting design (Tom Visser) and a reflective back screen (Jay Gower Taylor), which make the smoky greys of rising or falling clouds seem to float through the space and fall on the dancing bodies. The combination of Tchaikovsky's church hymn from the Mass of St. John Chrysostom, accompanied by Morten Lauridsen's chorus O magnum mysterium, with an original electronic, atmospheric score by the choreographer's court composer, Owen Belton, harmoniously combines all the components into one immensely powerful, immersive, and moving piece. Though, if I'm honest, regardless of the artistic performances of all involved, I struggled to shake the impression that, especially in those mass ensemble passages, the National Ballet of Canada were unable to connect as well and multiply the visceral tension and experience to create such a dramatically poignant impact or, conversely, an almost cathartically uplifting feeling as I took away from, say, The Seasons' Canon or, notably, the first act of Body and Soul, as performed by their colleagues at the Opéra national de Paris.

Written from a performance on 5 October 2024, Sadler's Wells, London.

Frontiers: Choreographers of Canada

Passion

Choreography: James Kudelka

Music: Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano: Zhenya Vitort

Costume design: Denis Lavoie

Ligh design Michael Mazzola

island

Choreography: Emma Portner

Music: Brambles, Guillaume Ferran, David Spinelli, Forest Swords, Lily Konigsberg, Bing & Ruth

Costume design: Martin Dauchez

Light design: Paul Vidar Sævarang

Angels‘ Atlas

Choreography Crystal Pite

Music: Owen Belton, Petr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Costume design: Nancy Bryant

Light design: Tom Visser