In Overture, Morau’s multi-disciplinary training in photography, movement, and theatre/dramaturgy, as well as his stylistic signature is evident, consisting of a movement deconstruction of the individual that is often reinserted into a pictorial, plastic ensemble context that works through synchronicity. Moreover, the Staatsballett dancers seem to have entered into complete harmony with his vocabulary, so much so that it appears to be their primordial language. Undoubtedly, the strong scenic and dramaturgical structure plus the soundtrack, three movements from Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 5, including the famous Adagietto, used by Luchino Visconti for Morte a Venezia (1971), were valuable allies in the success of this work.

Morau, recently appointed Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French Ministry of Culture and selected as best choreographer of 2023 by German magazine TANZ, is, in a way, at home in Berlin. He has visited the Tanz im August festival several times with his company La Veronal, but this represents his first time putting on a piece at the Staatsballett Berlin company.

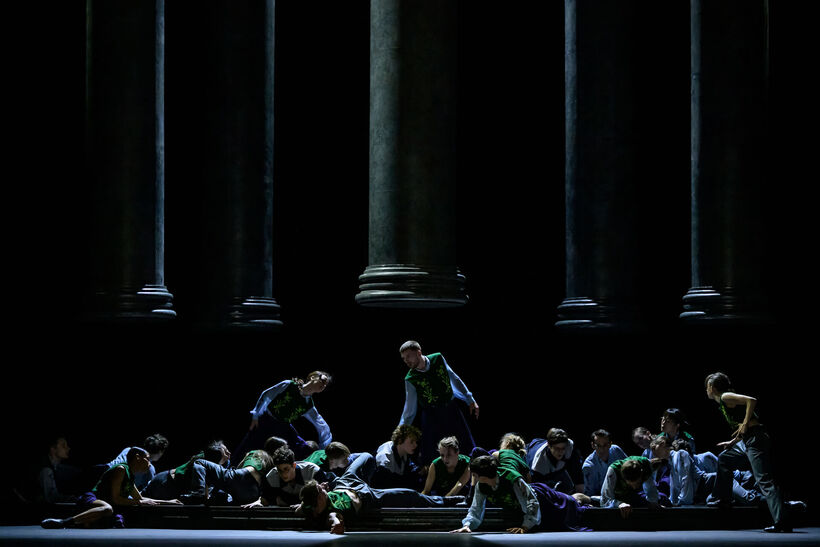

The beginning sees the thirty-six corps de ballet members moving as one body on the gigantic column. They are initially not entirely visible, lying across the stage. Under the dimmed lights and against the dark column, the pale bodies of the dancers stand out, creating a disturbing Caravaggesque light effect. Then, the column, which at first also seems to be a raft to which everyone is attached, is raised apparently by the dancers' effort alone (but actually by the theatrical apparatus) and takes on a vertical position. During the course of the performance, the columns increase in number, as if creating a forest or a palace, where the dancers, now dressed in skirts and blouses with folkloric references, almost play hide-and-seek, speaking an unknown language. Then the pillars diminish until they make way for a revolving platform, ending again with the column repositioned diagonally with the intention of being lifted up again.

Morau associates the image of the ancient column with power: as a uniting element between heaven and earth, it holds a power given to it by society. He reminds us of the democratic form, originated in antiquity, the evolution of civilisations and the associated social structures. But he also indicates that social structures and political order are temporary, that stability is transient. Columns, like cultures, will be erased again and begin anew, giving way to a new society. Not surprisingly, Morau dedicates this piece to young people, or rather, “the piece explores the problem of what happens to society when youth no longer initiate change.”

If the movement is less “marionette-like” and witty than, for instance, in Sonoma (2020), it is balanced by an extreme dissociation of the limbs, which amplifies its lyricism and drama. The standout protagonists are the group movements, both when very close and in contact, and also when at a distance, for example between the columns.

The column is reminiscent of the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968, by Stanley Kubrick) and, simultaneously, of the bone in the same film, i.e. elements belonging to several epochs, connecting different historical moments, whilst also capable of awakening consciences. Nevertheless, I believe that the column and Morau's use thereof, apart from being thematic and philosophical, is also truly architectural. Or rather, it serves as a vehicle for redesigning bodies in space.

By pure coincidence, a few days before attending the performance, I was visiting the Villa Foscari in Malcontenta (Venice), built in 1559 by the famous architect Andrea Palladio. By inserting the element of the classical column to the villa's portico, but in this case in sandstone, he rewrote sixteenth century architecture. For his part, Morau uses the element of the column to rewrite the architecture of a piece of choreography. It is through the column that we have the first agglomerations of bodies, the successive disappearances and reappearances of the dancers. With its physical and spatial weight, the column is thus an element of choreographic construction.

Angels’ Atlas: A Vanishing Point

If Overture can therefore be defined as an apocalyptic piece for its revelatory sense of destruction and reconstruction, Angels’ Atlas by Canadian choreographer Crystal Pite, was, in a way, prophetic of one of the apocalypses of our times. Indeed, it debuted just before the Covid-19 pandemic; considering its spiritual and dark tone, with the lighting effects which evoke the swirls of stars ready to disappear and reappear in a second, it worked well as an involuntary prelude to that period (its creative process was captured in the wonderful 2022 documentary, directed by Chelsea McMullan).

Addressing themes such as trauma and conflict, the former company member of Ballet British Columbia and William Forsythe’s Ballett Frankfurt, Pite does not require much introduction, suffice to say that in her thirty-five-year career, she has created pieces for companies such as The Royal Ballet, Nederlands Dans Theater, The Paris Opera Ballet, and for her own company, Kidd Pivot.

Like in Overture, the stage and sound installation are powerful agents of the piece. On the one hand, there is Jay Gower Taylor and Tom Visser’s Reflective Light Backdrop light installation, an analogue technology of aluminium foil and white crystals. On the other hand, Owen Belton's soundtrack combines choral music by P. I. Tchaikovsky (Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom Op. 41, No. 6), Morten Lauridsen (O Magnum Mysterium), and Belton's own electronic sounds, all played from tape.

The scene throughout the piece remains rarefied and suspended, as if to remind us that dance always takes place in a condition of disappearing. Unlike Overture, there is no dramaturgical narrative. Apart from the almost spiritual and profound soundtrack, it is the light installation that creates a constant dialogue with the dance and stage. The installation consists of “leaves” of light, seemingly lit fires, almost fatuous, but of sustained intensity, which are amplified or diminished in relation to the stage presence of the dancers.

With the exception of a moment when almost percussive and repetitive arm and torso movements takes centre stage, Pite’s language seems this time to be characterised by a continuous roundness, made up of expanded ports de bras, jumps in attitude, and deep cambré. If initially the movements are more earthy, as if the legs and pelvis do not want to detach themselves from the ground, while leaving the torso to become more aerial, towards the end of the performance, the dance becomes more ethereal, leaving room for lifts and jumps in the explosion of the four duets.

As if wanting to accompany us through an ephemeral state on the edge of an experience that is coming to an end (perhaps death?), Pite’s work expresses not an impossibility or nostalgia about the end or towards some unavoidable change, but a gentle acceptance.

Although in both pieces we saw the emerging corps de ballet’s strength, Morau’s approximately forty-five-minute work, more than twice as long as Pite’s, is dramaturgically intense, almost like a classical ballet or, as a friend of mine suggested, an archaic fairy tale. On the other hand, Pite’s piece is shorter, flowing extremely easily thanks to the lighting effects. At the same time, however, I found that Pite’s piece worked on an idea of movement accumulation, which could seem repetitive in choreographic language, almost trance-like.

In both pieces, the corps de ballet is undoubtedly the true protagonist, creating a unique but not undifferentiated body. In the two very different stylistic figures, the ensemble arises empowered, where its different physicalities and multiple breaths are united by the same energy.

Written from the performance of 5 May 2024, Staatsoper Unter den Linden, Berlin.

Overture

Choreography and Staging: Marcos Morau

Music: Gustav Mahler

Costumes: Silvia Delagneau

Set Design: Max Glaenzel

Lighting Design: Marc Salicrú

Dramaturgy: Israel Solà

Assistants to the Choreographer: Shay Partush / Valentin Goniot

Musical Direction: Marius Stravinsky

Staatskapelle Berlin

Staatsballet Berlin

Premiere: 28 April 2024, Staatsoper Unter den Linden

Angels' Atlas

Choreography: Crystal Pite

Music: Owen Belton

Additional Music: Peter I. Tschaikowsky / Morten Lauridsen

Reflective Light Backdrop Concept: Jay Gower Taylor

Reflective Light Backdrop Design: Jay Gower Taylor / Tom Visser

Set Design: Jay Gower Taylor

Lighting Design: Tom Visser

Costumes: Nancy Bryant

Choreographic assistance and rehearsal: Spencer Dickhaus

Staatsballet Berlin

Premiere: 29 February 2020, Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, Toronto, The National Ballet of Canada