New Ballet mécanique/ Half Life: Opera Ballet Vlaanderen between intellectualism and showmanship

Opera Ballet Vlaanderen’s 23/24 season commenced with a double bill combining a première of Richard Siegal’s brave but inaccessible New Ballet mécanique with the critically acclaimed showstopper Half Life by Sharon Eyal. The two performances employed widely contrasting approaches: whilst Siegal has created a world full of mechanical sounds and puppet-like body movements inspired by William Forsythe’s deconstructed classical ballet, Eyal embraces the plasticity of the mass pluriform body, the whole dance ensemble operates as a living organism, pulsating to a ferocious techno beat.

The original Ballet mécanique is a masterpiece of Dadaist filmmaking by Ferdinand Léger and Dudley Murphy from 1924. It should, therefore, not come as a surprise that Richard Siegal’s re-enactment is a disorienting and challenging piece. As the audience enters the lavish Ghent Opera, the curtains are already raised: huge green balls are bouncing on the floor, raised and released again by steel wires. In the background, the echoes of the bouncing balls resonate in a twisted soundscape created by Swiss stage and sound artist Zimoun.

As time passes, and we sit in silence, waiting for the piece to begin, the image of the bouncing balls plays with our senses. They bounce to separate rhythms, creating recurring forms. We can recognise the radical principles of mechanical repetitiveness and irrational imagery from Léger’s movie. The industrial sounds and the unnatural sight of the perpetually bouncing objects form something of a ‘symphony of machines’: music that finds its form in objects and materials, mathematically precise and rigid, with repeating echoes that form waves of sound, like wind from extraterrestrial desert landscapes.

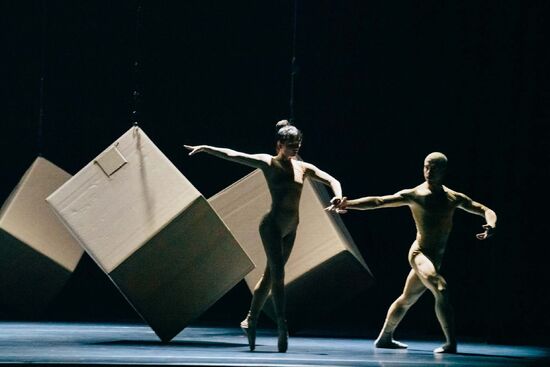

The audience is left hypnotised by these self-levitating balls for a good fifteen minutes. Then the dancers enter. From that point on, one Dadaist image follows another, created with boxes, tin barrels, a big wooden board fixed at an acute angle, a moving ice sheet, along with different costumes. Based in Antwerp, Austrian haute couture designer Flora Miranda has created a set of costumes that manages to be both bizarre and understated at the same time: a white fashionista tutu, with fabric that is torn apart and flies around the dancer’s body; white and yellow shirts that have a black ‘O’ on the chest; weird 70s sci-fi style pieces that cling on to the dancers’ bodies, creating unnatural opposite movements; the dancers not wearing these most extravagant examples don beige bodysuits that reflect every muscle and every little movement they make.

In Siegal’s work, humans and objects are equally important: The dance develops as a response to the art installation, sometimes finding a way to communicate with the objects, sometimes merely mimicking them. Without any narrative guidance, New Ballet mécanique embodies Zimoun’s credo, where spaces are constructed in a way ‘that one can enter, stay in and leave again. There is no true beginning or end.' In this piece, the audience is given a great deal of responsibility: It’s up to us to decide whether and how to explore the altered dimensions and strange possibilities.

The ability of the dancers is evident in the demanding movement vocabulary, where clear ballet steps – pirouettes, jumps, en pointe steps, arabesques – become elongated, exaggerated, and sometimes just strangely animalistic, for example assuming a frog-like second position. Siegal danced under Forsythe and, as a choreographer, he takes Forsythe’s experimentation further. While Forsythe’s dancers appear close to losing their balance, Siegal’s crash onto the floor. While Forsythe’s dancers remain fluid in their motions, Siegal’s move chaotically, as if dancing several moves simultaneously. Somehow, it flows perfectly, like a well-oiled ‘machine’, as if the mechanical puppet-master of the bouncing balls is still pulling the strings.

Now, days after the show, I reconstruct my inner thought process during the performance: initial fascination, then losing myself in a fever dream of strangeness, and finally opening up to pure aesthetic pleasure of the piece without bothering to look for any overarching message or make sense of it all. The reception of the audience was lukewarm and I had to ask myself if any of us had really seen the same performance, or if we had all been lost in our own rambling minds, one fleeting association after another.

Clubbing at the Opera

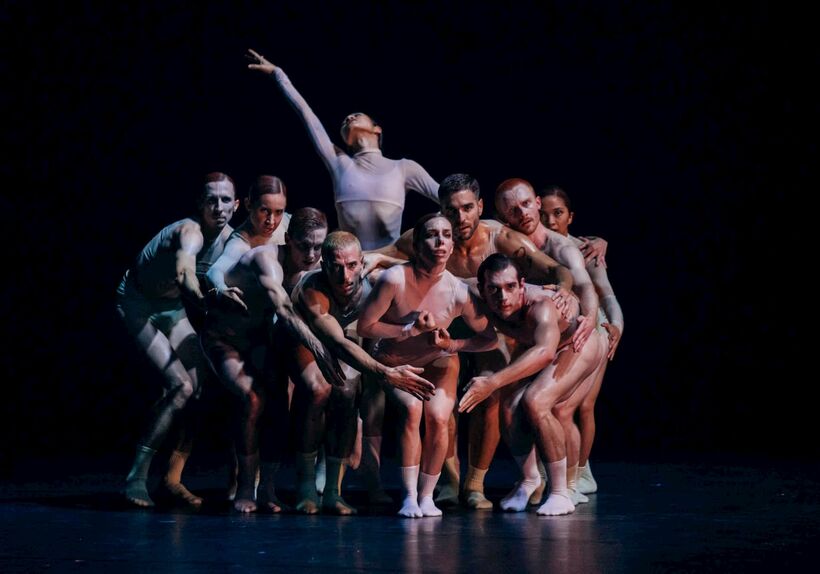

Half Life, on the other hand, ended with resounding applause. I expected nothing less. The first time I saw her work it was refreshingly innovative and absorbing. Eyal’s distinctive, intense, and emotional aesthetics and vocabulary beats through layered techno music (composed by Israeli Ori Lichtik), sending vibrations straight to the our core. With an ensemble of capable dancers with classical backgrounds, she stages a piece that is hard to put into any particular box. Is it maybe a mosh-ballet crossover?

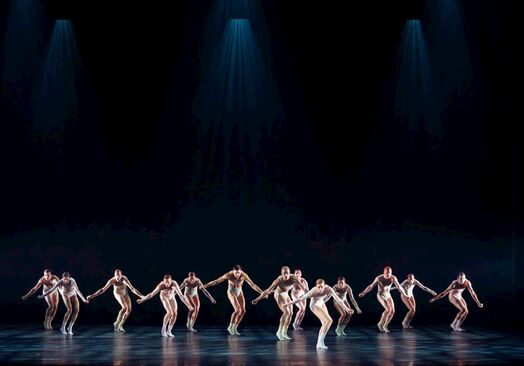

After New Ballet mécanique’s scenography and dramaturgic abundance, we are confronted with a piece of repetitive minimalism. But while the movements are repetitive, the small developments within the group create a constant dynamic. It starts with two dancers on stage, Philippe Lens and Yaiza Davilla Gómez, while the dark vibrations of Ori Lichtik’s music create an ominous atmosphere. The dancers are repeating their own simple but demanding movements: Lens repeating a kick to the left, followed by an exaggerated pelvic thrust. Next to him, Gómez performs a samba-like roll of the shoulders marching on the spot. While she seems less dominant next to the physicality of her partner, we quickly understand that this is far from the truth. When the mass of bodies of the ensemble slowly enters the stage as one big multi-human organism, Gómez is the dancer who rebels, who stays free from the conformity of the masses. Her simple roll of the shoulders becomes the recurring theme of the piece.

Throughout the performance, with the imposing techno beat as a constant backdrop, the dance develops as an exploration of group dynamics. The rhythm is relentless, the physical demands on the dancers are palpable. The formations vary, sometimes they form duets or triplets, at other times single dancers separate themselves from the collective to follow their own movements. While Lens made a big impression in the beginning, later he succumbs more easily to the group. Gomez maintains her individualistic movements throughout. The individual and the collective, socialisation and liberty, conformity and free will (yes, we get the point after about 10 minutes).

Where Siegal leaves us searching for answers, Eyal spells out her message with capital letters and repeats it relentlessly. The audience’s preference was clear. But while the intensity and group coordination of Eyal’s piece is marvellous to watch, I can’t shake the feeling there is something crude and unimaginative about the loud and insistent minimalism of the piece when you are already familiar with her style. On my way home, the repetitive images stayed in my head like an irritating pop melody, completely drowning out the more nuanced and complex reveries I experienced watching the first piece.

Written from the performance of the 28 October 2023 at Opera Gent, Ghent.

New Ballet mécanique

Choreography: Richard Siegal

Scenography and Sound design: Zimoun

Sound Direction: Till Hillbrecht

Costume Design: Flora Miranda

Lighting Design: Matthias Singer

Dancers: Anais De Caster, Claudio Cangialos, Nicha Rodboon, David Ledger, Kirsten Wicklund, Philipe Lens, Nicola Wills, Austin Meiteen, Morgana Cappellari, Rune Verbilt, Madison Vomastek, Lateef Williams, Esther Perez, Aleix Labara i Cerver, Elisabeth Callebaut, Tiemen Bormans

Half Life

Choreography: Sharon Eyal

Cocreation: Gai Behar

Composition: Ori Lichtik

Costume Design: Rebecca Hytting

Lighting Design: Alon Cohen

Dancers: Jasmine Achtari, Claudio Cangialosi, Yaiza Davilla Gómez, Brent Daneels, Anais De Caster, Nelson Earl, Christina Guieb, Philip Lens, Allison McGuire, Morgan Lugo, Esther Perez, Austin Meiteen, Nicha Rodboon, Louis Thuriot, Niharika Senapati, Shane Urton, Kirsten Wicklund, Rune Verbilt