Rush – Imaginative Retrospective with a Touch of Humour

In dance, even the most acclaimed performances quickly become distant shadows in the past. How can we retain – or reclaim – what once was? In Rush, premiered at STUK this February, Mette Ingvartsen and Manon Satkin took it upon themselves to preserve the memories of their own long standing collaboration, to keep it alive and relevant. What they envision is ‘a living retrospective’, a re-enactment, whilst also being a fully independent piece that works on and through its own principles and struggles: A personal dance history embedded in the body of Satkin.

On a large, empty stage, seemingly random objects are carefully arranged: a table, two air-blowing machines, several sculpture-like, golden space blankets, and a stereo. Suddenly, we hear a woman over the speakers: It’s Manon Satkin. With a calm and faintly seductive voice, she guides us through what a performer experiences during the final few minutes before entering the stage. All the small rituals, the shared nervousness with her co-performers, the cold sweat, and even a last-minute pee, because, as she explains, childbirth has brought some new leakage issues to nude performances. After 20 years, the stage fright is just as present.

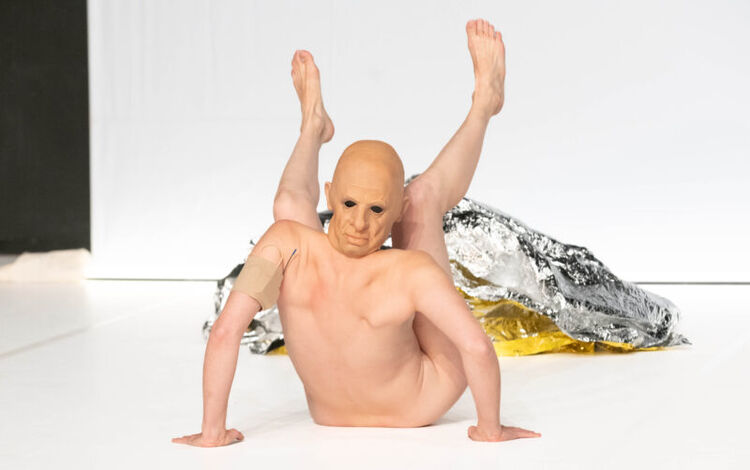

As the sound of peeing rings through the hall, an immediate connection is established between the audience and the performer. You can hear quiet laughter around the room, a sign of recognition. This mixture of fragility, intimacy, and empathy is the magic ingredient in Satkin’s performance, established before she even sets foot on stage. When she finally arrives, nude, she puts a full rubber mask on the wrong way round and starts performing moves from Manual Focus,made in 2003. We see her not as not just any performer but as that same voice that confided in us from behind the stage some seconds before. When she casually breaks character to tell us her memories of how this piece came to be, what it was about, and what performing it with her group was like, she has the audience in the palm of her hand.

Following this formula – a mixture of re-enactment, narrative, and personal anecdotes – over the next hour-and-a-half (which, amazingly enough, felt way too brief), Satkin recreates, retells, and re-invents her past performances, referring to pieces such as To Come (extended), Why We Love Action, The Artificial Nature Project, Speculations, and 7 Pleasures. Playing with memory and imagination, she is able to evoke these ensemble pieces through her sheer energy and narrative wit. She creates a safety-blanket air-dance with leaf-blowers, she jumps naked through the rows of spectators, and she demonstrates the fifteen-person human intercourse-snake of 7 Pleasures all by herself. In the next breath, she tells us a story and asks us to shake our hands and bodies as if our lives depend on it (and we do).

Mette Ingvartsen is known to challenge and imagine new conceptions of being and existing, to explore micro and macro structures that define and redefine us. This is the case in all the pieces that she refers to and re-enacts in Rush. She investigates the hidden mechanism behind the principles that govern and form our emotions. Thus, in Why We Love Action, with its Chaplinesque slapstick, she deconstructs green screen technology by extorting gestures from movies, gestures that in a different context become absurd, meaningless, and funny. Always using subtle humour, she tackles the deep manipulation of our senses and tries to redistribute them from within the dance and a state of self-reflection.

The piece’s themes appear to be in contrast with one another: from desire, joy and madness to crying and violence; from gender transformations to environmental concerns. But one guiding thread remains constant: the desire to revisit the past, to transform it, and to take the audience there. After twenty years of performing, Satkin stands boldly in front of her public, her body changed by time and ageing. It is a body that has also given birth, a body that has mutated in and with the pieces themselves. But even more, in standing there alone, it is a body that gathers together all the bodies of the other performers that have danced with her. A body that is at the same time old and young, male and female, human and non-human.

She is not alone. We are here with her. The audience is not only the backdrop to her self-exploration. Rather, the piece is a deliberate attempt to share, to give us all a small taste of the past, of her life and her performances. At one point, she literally invites us to join in and what follows is a moment of pure collective sensation as several audience members join her on stage to produce a collective, choral-like orgasm noises repeating sounds from their headphones. The intensity, intonation, and duration of the breathing are crucial for this part. While they simply repeat the voices, with their muscles tensed, heads bent slightly backwards, and with a twitchy rigidity to their posture, they evidently connect to something that the body also recognises. At this point, it was no longer a re-enactment as much as a shared exploration of a singular moment of community.

As should be clear by now, this piece is much more than a collage of the ‘greatest hits’ of Manon Satkin and Mette Ingvartsen’s 20 years of collaboration. While ostensibly starting with the ambition to look back, reconstruct, and preserve their own work, the performance outgrows this modest aim. It is not so much about revisiting the performances as about exploring the experience of performing and the way in which the performer and audience shape the moment together. Satkin asks for a contagion of affects, vibrations, and a collective experience that goes beyond mere intellectual perception.

However, as much as the audience is a strong presence in the performance, that is only because Satkin wishes it to be the case and shapes it. It is her remarkable stage presence (which includes not only dance and narration but also a seemingly limitless range of expressions and action-movie stunts) that keeps us mesmerised the entire time. In Rush, the body becomes its own archive, but as dance scholar André Lepecki formulates, the archive also becomes a body.

Written from the première of the performance of 1 February 2024 at STUK, Leuven, Belgium.

Rush

Concept and choreography: Mette Ingvartsen

Performer: Manon Santkin

Choreographic assistant: Thomas Bîrzan

Technical direction and lighting design: Hans Meijer

Sound technician and sound design: Milan Van Doren

Technician: Jan-Simon De Lille

Music: Will Guthrie, Peter Lenaerts, Gregorio Allegri, Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich, Benny Goodman

Management: Ruth Collier

Production and administration: Joey Ng

Communication: Jeroen Goffings

Production: Great Investment VZW

Co-production: STUK co-financed by the Creative Europe programme of the European Union as part of the DANCE ON PASS ON DREAM ON.