First of all, congratulations on winning the Thalia Award! What was your very first thought or emotion when you heard your name announced?

Thank you very much. When I heard my name, my first reaction was shock and pure nervousness about having to give a speech (laughs). My immediate thought was: Now I have to go up there, give a talk, and hold the award! I had already been thinking about the speech before the ceremony, and I remember eventually holding my head in my hands and saying something in Italian — though I honestly can’t recall what. It was a rush of emotions all at once — shock, nerves, and at the same time immense happiness.

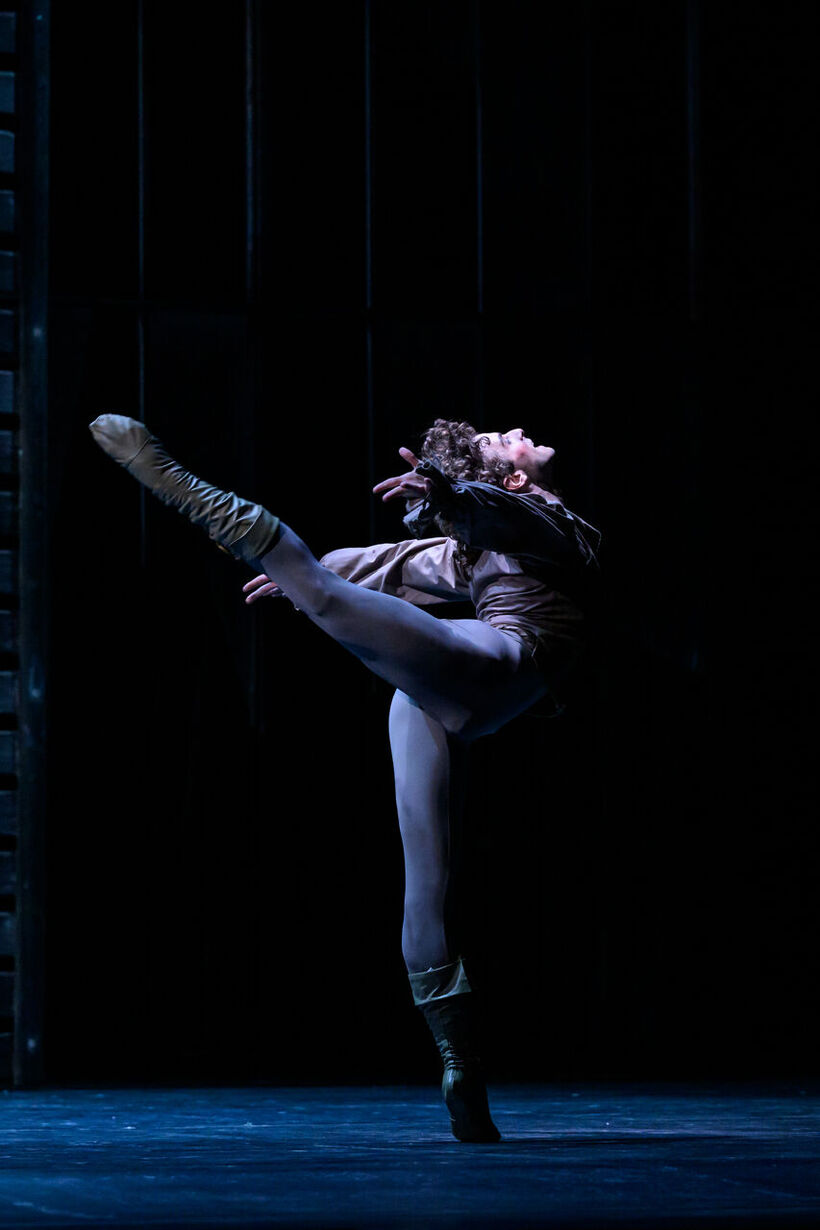

I love drama, but only on stage! says Thalia Award winner Federico Ievoli

The career of Italian dancer Federico Ievoli, currently a first soloist with the Czech National Ballet, has shown a consistently upward trajectory over the past decade. He has gradually progressed from corps de ballet roles to leading parts in both the classical and contemporary repertoire, earning the attention of general audiences as well as critics. A significant confirmation of his artistic qualities came when he received the Thalia Award last November for his performance as the Chevalier Des Grieux in Kenneth MacMillan’s iconic ballet L’Histoire de Manon. According to the Thalia Awards jury, he “creates a fascinating portrayal of a tragic romantic character […] and uses his experience as a principal dancer to shape a dramatic arc, gradually transforming from an innocent young man into one broken by love and fate.”

How important is the Thalia Award to you personally, especially as an international dancer building your career in the Czech Republic?

When I joined the National Theatre in 2015, I wasn’t aware of the award, even though it is nationally very well known. Over the years, I gradually came to understand its value and prestige, especially as I saw colleagues and artists from other companies receive it. In a way, I’m glad I won it now, at a time when I fully understand how significant it is and how lucky I am. Receiving the nomination was already a big thing and I was very happy about it. As an international dancer, I feel deeply honoured and grateful, but I don’t see this award in terms of nationality. For me, it’s about the artistic work and the artist behind it, and I truly appreciate that the jury focused on the performance itself and the artistic result.

How does such a recognition influence your motivation—does it bring pressure, reassurance, or a renewed sense of freedom on stage?

I understand that receiving such an important award can bring a certain sense of pressure — a feeling that you now have to give 300 percent all the time. But in reality, I’ve always had that mindset. After several years as a first soloist, I know I need to give my best, just as I did when I was in the corps de ballet or a demi-soloist. In that sense, the award doesn’t change much. Of course, it brings personal satisfaction but I keep it to myself and try to stay grounded and relaxed. At this stage of my career, I want to enjoy dancing rather than add extra stress. I already put enough pressure on myself — my focus is simply on doing well and enjoying every performance.

You obtained the Thalia award for the role of Des Grieux in the Czech premiere of Kenneth MacMillan’s L’Histoire de Manon. What did it mean to you to be part of introducing such a famous work to a Czech audience? Did you feel more responsibility and awareness during the rehearsal process?

Two years ago, when our artistic director Filip Barankiewicz announced that we would perform L’Histoire de Manon, I was thrilled — it was a role I had always wanted to experience. Bringing this piece to a Czech audience for the first time was incredibly exciting. The style was completely new for us, and everyone — from the corps de ballet to the first soloists — was fully engaged and trying to give their best. It was amazing to be part of a company so committed, and I felt we all put a lot of effort into making the performance as strong as possible.

MacMillan’s choreography is known for its emotional intensity and psychological realism. How did you find the balance between control and emotional abandon?

Finding that balance wasn’t easy at first. MacMillan’s choreography is both technically demanding — with many variations and pas de deux — and emotionally intense, requiring a character who changes throughout the ballet. Over time, I learned to go with the flow rather than overthink the technique.

What makes MacMillan‘s work so special is its truthfulness and sense of freedom. From day one, Robert Tewsley who staged the ballet for us, covered all the mirrors in the studio. At first, we were shocked, but it forced us to focus on the connection with our partners and the characters rather than checking ourselves. You aren’t projecting to the audience; it’s about living the story. Dancers are even allowed to create their own subplots in the background, making each performance feel like a movie. Despite the technical challenges — especially the nerve-wracking solos at the beginning — I can rely on the flow of the ballet. It’s an extraordinary experience, and for me, one of the best ballets I’ve ever danced.

What did this ballet teach you about your own limits?

This ballet taught me that I can actually dance it (laughs). When I was cast at first, the choreography felt overwhelming — I wondered if I could perform it on stage with all the lights, costumes, and stamina required. But at 32, in this more experienced stage of my career, I’ve realized I can still learn, grow, and improve. Receiving recognition like the Thalia Award and acknowledgment in Italy is wonderful, but I’m far from done. I’m aware of my strengths and weaknesses, and every day I work to improve. Seeing my colleagues’ artistry inspires me, and this ballet reminded me there’s always room to grow.

Des Grieux evolves dramatically across the three acts. How did you structure the character’s physical and emotional arc through movement rather than gesture? The jury also praised the way you handled his development…

Ballets where a character evolves are the most exciting — like Lensky in Onegin or Romeo in Romeo and Juliet — and Des Grieux is one of them. In Act I, he’s romantic and shy; in Act II, angry and upset; in Act III, desperate. Conveying this takes practice, both technically and emotionally. That’s what makes it so fascinating — I get to be different in each act.

With experience, I’ve learned to have an internal conversation with myself and my partner about what I want to express. Early in my career, I enjoyed portraying someone I wasn’t, but now I’ve realized it works best to be myself in the situation — truthful to the story and the character. When you are authentic, the audience can believe it.

Partnering in Manon is exceptionally complex, both technically and emotionally. How did you and your partner, first soloist Aya Okumura, build the trust needed for such exposed choreography?

Partnering in Manon is very challenging, especially the first duet — it’s full of heavy lifts and uncomfortable grips, and you’re already dead tired from the opening solo work. Then, after a two-minute costume change, you go straight into the bedroom pas de deux, one of the best-known duets in ballet, where everyone expects perfection.

Aya and I have danced many ballets together, so we trust each other completely. She’s an amazing artist - fearless on stage, always fully in the role, and that pushes me to match her energy. We share a similar work ethic, experiment in rehearsals, and never allow drama or selfishness. Dancing with her has given me more confidence as I have to be 100 percent committed and present on stage.

.jpeg)

From a dancer’s perspective, what do you believe makes L’Histoire de Manon endure as a cornerstone of 20th-century narrative ballet?

MacMillan wanted to portray real people on stage, not just perform for the audience, and that’s what makes his ballets so special. Of course, there are many technically challenging moments, but every step has meaning. The solos and pas de deux are not just technique for technique’s sake. For example, the final “swamp” pas de deux in Manon is one of the most intense experiences I’ve ever danced — the girl is completely broken, and I’m there to catch her. Moments like this, combined with the music by Jules Massenet, make the ballet iconic, and every dancer dreams of performing it at least once.

Looking back to the beginning of your dance journey, when did you first realize ballet would become your life’s path?

I didn’t have a single defining moment, but I’ve always been drawn to music, and dance naturally followed. I started dancing at seven in a private school, then joined the San Carlo Ballet School. I wasn’t happy there — the strict training at such a young age and focus on building technique and strength felt overwhelming. As a student, I performed small extra roles, like holding a lantern in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet, which allowed me to watch the principal dancers perform from up close and that made me fall in love with dance. When I later joined the Accademia Teatro alla Scala, my passion even deepened.

Accademia Teatro alla Scala in Milan is one of the most prestigious ballet schools in the world. How did that experience shape your discipline and expectations of yourself?

La Scala gave me the best education I could hope for. I was there from 15 to 18, surrounded by people who shared the same focus, living in a bubble dedicated to ballet. It wasn’t always easy, but we got to perform some nice repertoire and already worked with choreographers. It was during this time that I truly understood I wanted to pursue dance seriously, and it set the foundation for the discipline and standards I hold for myself today.

Moving from Italy to Prague was a major step early in your career. Why did you choose this city, and what were the biggest cultural or professional adjustments you had to make?

Finding a job after La Scala was complicated — auditions are tough, and competition is intense. I applied to many places, then did a private audition with Petr Zuska in Prague, waited for the public one, and was finally offered a contract a month later. I was overjoyed. I had always wanted to perform in a theatre that balanced classical and contemporary repertoire, and this company had it all.

Prague became my artistic home. Even starting in the corps de ballet, performing classics like Swan Lake and La Bayadère, felt exciting. Living here required some cultural adjustments — I’m aware it’s not Italy — but I’ve embraced the city and the country, exploring the positives while appreciating Italy when I visit.

.jpeg)

Today’s ballet world emphasizes versatility. As a first soloist who performs both classical and modern repertoire, how do you balance classical purity with contemporary demands?

In a major company today, you must be versatile. Classical and contemporary require different skills, and with contemporary works, you need freedom and adaptability. I love that our repertoire constantly changes — one week classical, the next contemporary — it keeps us challenged but also entertained. It’s demanding on the body, but with experience I know how to work smart and recover. The variety keeps me motivated and inspired.

Your performances are often praised for their dramatic depth. How do you work on the acting side of ballet, where words are absent?

I love drama — on stage only! (laughs). Opera also inspires me; the music and emotion give ideas for expression. On stage, I focus on being truthful to myself — as I mentioned before, I often have inner conversations, and usually in Italian, so it would be funny for the audience to hear them (laughs). The ballet masters and artistic team are important, but a lot comes from experience and self-awareness. Luckily, we get to perform many shows so I can refine my expression continuously.

Is there a role or choreographer that has significantly changed the way you see yourself as an artist?

Many roles and choreographers have shaped me, especially in the early years when I wanted to give my absolute best in everything. Working with Jiří Kylián was transformative — being in the studio with him was inspiring; his direction was simple but profound. Roles like Lensky or Romeo have also shaped me over time. I see how my interpretation evolves, and with experience, I’ve learned to bring more of myself into each character, which makes any dancer a more mature artist.

.jpeg)

When audiences watch you on stage, what do you most hope they feel or take with them after the performance?

I don’t overthink what the audience feels. I hope people enjoy the performance and that it stays in their minds afterwards. In today’s world of social media, where we see only perfect moments, I want them to appreciate the authenticity and spontaneity of a live performance, including its imperfections.

Besides being a professional dancer, you are also a student with a degree in sport management and a focus on dancer health. How has this knowledge changed the way you train, rehearse, or recover?

After high school, I wanted to continue studying, but early in my career, dance was all I was able to focus on. During the pandemic, I pursued a bachelor’s in Movement Science and soon a master’s in Sport Management, learning about anatomy, pedagogy, nutrition, and training principles. I even did my bachelor thesis on Romeo and Juliet. This knowledge has changed how I train, recover, and prevent injuries. For example, I started weightlifting to increase strength and stamina for partnering. Ballet has a rich tradition that I have always respected, but combining it with science helps dancers perform better and extend their careers.

Physical preparation-wise, is there anything you would recommend to aspiring dancers?

I think young dancers should have more awareness of dance medicine and cross-training to prevent injury, improve stamina, and boost their performance. They should keep their minds and eyes open to see what works best for them. Strength training, stamina work, and awareness of the body are crucial, especially during busy seasons. Ballet training alone isn’t enough; supporting your body scientifically can help you perform with more ease and reduce fatigue during demanding roles.

.jpeg)

Dance is a major part of your life. Outside the studio, what usually fills your days?

I’m quite a simple person (laughs). I enjoy relaxing at home, watching series, trying the best pastries and cafés in Prague, and playing video games. I spend a lot of time with my boyfriend, Danilo, who is also a soloist, and my family when they visit from Italy. Having a life outside ballet helps me focus on my work and maintain a healthy balance, which also improves my performances.

Finally, after winning the Thalia Award, what artistic goals or roles are you most eager to pursue?

I still can’t believe I received the prize. My goal now is to keep learning, improve my weaknesses, and enjoy the rest of my career without additional stress. When you’re younger, you approach everything aggressively, trying to do it all. Now, I want to savour every performance, stay calm, and appreciate the time on stage, because the career is short and there are bigger challenges in life than a single show.

Federico Ievoli was born in Naples, Italy. After completing his dance studies at the Accademia Teatro alla Scala in Milan. In 2015, he joined the Czech National Ballet in Prague, where he rose through the ranks—demi-soloist in 2019, soloist in January 2020, and first soloist in April 2021.

On stage, he shines both in lyrical and psychological roles as well as in performances requiring dazzling technique and strong dramatic expression. In the classical repertoire, he has stood out as Romeo in Romeo and Juliet (Petr Zuska), Lensky in Onegin (John Cranko), Chevalier Danceny in Valmont (Libor Vaculík), Bobbie/Nutcracker in The Nutcracker – A Christmas Carol (Youri Vámos), Prince Desiré and the Prince of the West in The Sleeping Beauty (Márcia Haydée), and James in La Sylphide (Johan Kobborg). In the Czech premiere of L’Histoire de Manon (2025), he took on the title role of Des Grieux, affirming his stature as a dramatic performer. In Mauro Bigonzetti’s Kafka: The Trial, he impressed as both Josef K. and the Painter. His compelling performances also include Stanley Kowalski and Allan’s friend in A Streetcar Named Desire (John Neumeier).

In contemporary work, he has made his mark in choreographies by Jiří Kylián (Petite Mort, Bella Figura, Gods and Dogs, Six Dances, Symphony of Psalms), Ohad Naharin (Decadance), Emanuel Gat (Separate Knots), Alexander Ekman (Cacti), Glen Tetley (The Rite of Spring), and in the bpm project (Eyal Dadon, Sharon Eyal & Gai Behar, Yemi A.D.). In Ballet 101 by Eric Gauthier, he displayed both his technical flair and comic timing.

Federico regularly appears at international ballet galas: Ballet Galas in Lappeenranta and Tampere (Finland, 2017 and 2019), Gala in Shenzhen, China (2018), International Ballet Gala in Ostrava (2019), Velvet Gala at Prague’s Estates Theatre (2019), and the Starlight International Ballet Gala in Osaka, Japan (2024). In 2023, he received the Sfera d'Oro per la Danza award as the best Italian dancer working abroad. As a guest artist, he has also performed with the Slovenian National Ballet in Ljubljana (The Nutcracker – A Christmas Carol) and with Thüringen Staatsballett in Gera, Germany (The Sleeping Beauty).

Source: https://www.narodni-divadlo.cz/en/profile/federico-ievoli-1609792

.