Was that when you fell in love with dancing?

Definitely. At first, school was fun for us; we used to play soccer with the boys before practice. I remember Mr. Halász coming in on the first day and saying, "Boys, where are you? You're late. If you want to dance to the fullest, now is the time to get to work." We were stunned... During training with him, we laughed and worked hard. The professor became like a second father to us. My brother, Mr. Halász, and I have been very involved in our studies ever since.

As you said, your parents weren't with you, but they were a great support. Your father was a huge fan of yours, he collected all the reviews, articles, and video recordings, and he went to the premieres. Did you talk to him about your roles, about your choreography?

Dad often came to the conservatory and experienced our studies with us. He also fell in love with dance. He would sometimes check on us, film our training sessions and rehearsals, and then we would watch the recordings at home and immediately see what needed to be improved.

When Dad said he didn't like something, we were always disappointed. On the other hand, when he praised us, I was extremely happy. I gradually got used to his evaluations, and when they were missing later on, I felt that something wasn't quite right. I gradually had to learn to trust myself more...

So he was filming you at the conservatory, he was your archivist from the very beginning...

Yes. Sometimes the filming got on our nerves a little at the time, but today I can see how much it helped my brother and me. We also watched videos of Baryshnikov and Nureyev and studied how they jumped, how they did different kinds of pirouettes, how they worked with their bodies. We filmed ourselves in the studio after class to see what we could improve. The conservatory janitor was unhappy with us. Every evening he had to kick us out because we were the last ones in the school and he couldn't go home.

Is there anything you didn't get to ask your father?

(He sighs with a smile.) I would probably discuss raising children with him—Honzík will be nine, Blanka seven. I sometimes complained when my dad was at school. Today I understand, I also want my son and daughter to have a good school and education. I would like to talk to him about my children.

Maybe he can hear you, up there...

Maybe...

We were thrilled in Hamburg

In Tokyo, at a choreography competition, you caught the eye of John Neumeier as a 15-year-old dancer, and he presented you with an award at the Prix de Lausanne in 1992. At that time, you and your brother Otto turned down his offer to study in Hamburg, and Neumeier waited for you. You graduated from the conservatory and immediately joined him at the Hamburg Ballett. It was a great opportunity, but at the same time probably a lot of pressure. How did you feel about it at the time?

When we joined the company at the age of eighteen, we didn't speak English or German very well yet, so we had to get used to Hamburg. A new city, a new apartment... and our parents weren't with us. As I said, our family has always been very close, so it was a big change for us.

But we were excited about the work in Hamburg. We were busy, and I was able to buy my first stereo player with my earnings from dancing. I felt like I was starting to stand on my own two feet. John gave us solo opportunities even though we were dancing in the chorus at the time. I had to learn quickly and be perfectly prepared—I had no experience with the current repertoire at that time. I borrowed VHS tapes with the choreography so I could learn it, not hold anyone up, and not embarrass myself.

You didn't embarrass yourself. I remembered some of your roles on video. You danced lightly, naturally, technically brilliantly...

What I enjoy about dancing is the energy. Yesterday I was at the 80th anniversary performance of the dance conservatory (editor's note: he Dance Conservatory of the City of Prague), and when I saw the boys lightly slapping their thighs in the folk dances, it bothered me. My hands used to be completely red. Folk dance at the conservatory teaches you not to be afraid of the stage; it's not so much about technique, but mainly about experience. It's important to convey the joy and energy that belong to folk dances.

What I miss most in schools and ensembles is when dancers don't fully immerse themselves in the choreography. I don't like it when I see dancers thinking about technique, how to hold their partner, and so on. It's important how the choreography is interpreted, how the dancers perceive it. Every movement has its reason.

Can they learn this at school?

Yes, they can. It must be required of them, and they should have someone with them who can bring it out of them. It's not about teaching technique, but about teaching artists.

John and I got to know each other very well.

You were excellent in roles from the classical repertoire, but with Neumeier you had the "final say" in his choreographies, where he deviated from purely classical technique. He relied on you and Otto, for example, in Nijinsky and Illusions – Like Swan Lake. How do you remember working with him?

Neumeier's neoclassical choreographies were very difficult, and I would even dare to say more difficult than typical classical ballet choreographies... We wore our bodies out, because when you only dance classical ballets, you are in one style, but in Hamburg we alternated between modern, classical, and neoclassical, and our muscle tone had to adapt to that. But to your question.

Neumeier was very inspired by me, my brother, and other dancers in the ensemble. John demonstrated a movement, and we did ten more. And he chose from them. It was a creative ping-pong that we all enjoyed. Sometimes you get stuck in a choreography, you don't know how to proceed, and it's nice to have creative dancers.

I danced in Hamburg for thirteen years. John and I got to know each other very well during that time, and I really enjoyed working with him in the studio. He was around fifty at the time, full of energy, and we often laughed while working. But to be honest, after thirteen years, some things started to bother me. John had two faces. When working on a new choreography, you were his best friend, but a few days after the premiere, he barely even said hello to you. Whenever I wrote him an email, he didn't reply. And I'm far from the only one to whom this happened. That always upset me – and it was one of the reasons why I eventually left Hamburg for another company.

Neumeier had a great PR person who was able to secure media coverage not only for him but also for the dancers. When a new PR team came in later, everything changed. We gave our all in the rehearsal room and on stage, but outside it looked as if it was all about the boss.

In the documentary A Life Devoted to Dance about Neumeier, one critic says that he was kind and friendly. Is that true?

He was kind and friendly, and I enjoyed working with him most when a new ballet was being created. The creative atmosphere was always magical. But when rehearsing the repertoire, he sometimes lacked understanding. He tended to forget that we were people—young people who were developing not only as artists but also as personalities. During rehearsals, I witnessed several arguments, which always upset me. Interestingly, when John was guesting elsewhere and working with other companies, he behaved differently. He was often very strict with us, his dancers.

When I create choreography myself, I realize more and more that without dancers I would be nothing. I just show, give impulses, and come up with ideas – but they are the ones who stand on stage and bring my choreography to life. Praise is the least a ballet director can give his dancers.

Neumeier's neoclassical choreography was very difficult, and I would even dare to say more difficult than typical classical ballet choreography... We wore our bodies out, because when you only dance classical ballet, you are in one style, but in Hamburg we alternated between modern, classical, and neoclassical, and our muscle tone had to adapt to that.

Choreography is different work than when you "just" dance.

Do you ever lose your temper in the studio?

Not anymore. But when I was dancing and I thought something wasn't right, I let it show.

Anyone who hasn't been a choreographer has no idea what it entails...

It's impossible to understand, it's about experience. It's a completely different job than "just" dancing. As a choreographer, I am responsible for the entire process. Before I start creating, I immerse myself in searching – for information, ideas, feelings, and even small impulses. Gradually, costume and set designs emerge. The preparations take a year or two. And then there are two to three months of intense work in the studio. It's always a race against time; the premiere can't be postponed. You have lots of ideas and thoughts that you want to realize, and then you find out, for example, that there's no money for costumes, something can't be made... A dancer can't manage the moves I've come up with, someone gets injured. Something is always changing during the process of creating a new ballet. It depends on how much you insist on everything, whether you allow the process freedom, adapt... Sometimes something even better than I originally imagined can emerge. And sometimes you have to stand your ground. There are days when it all comes together easily, but there are also moments when I wonder if it will all work out. And then there's the premiere, the applause... But still, that "blank, unwritten page" at the very beginning always scares me a little – but at the same time, that's where I feel the greatest freedom.

Are you a perfectionist?

I am, I can't do without it. Every detail is extremely important, and the set design, costumes, choreography, and lighting must all be in perfect harmony. Of course, sometimes you have to compromise – that's also part of choreography.

And how was it in Cyrano, your latest production in the Czech Republic?

From the beginning, I was surprised by the acting of Shoma Ogasawara and Anna Yeh (editor's note: the performers of Cyrano and Roxane), because Japanese dancers rarely show their emotions. They are meticulous, extremely hard-working, but tend to hide their feelings. I was all the more pleased that the collaboration with them was so successful.

Nadina (editor's note: Nadina Cojocaru, wife, artist, and costume designer) and I worked very intensively with the entire ensemble of the National Theater Brno on every gesture and movement so that it would express something. In narrative ballets, it is crucial for me that the dancer is truly present on stage and plays their role authentically. The ensemble was not very used to rehearsing not only technique but also acting in the hall. Nevertheless, I feel that everyone has improved significantly.

The problem is that when I leave for another project after the premiere, this new experience can easily be lost. It is important for the dancers to preserve the expression and connections we have created together. This must be constantly monitored. Neumeier always pays close attention to dramaturgy and direction, and this is also essential for me.

It seems to me that narrative is closer to you than abstraction.

I agree, narrative is probably closer to me than abstraction. I liked narrative ballets as a dancer, and I still like them today as a choreographer. I don't think completely abstract ballet actually exists – the audience always creates its own story, regardless of the author's intention. Personally, abstract ballets rarely interest me. On stage, there is always a dancer who has some kind of relationship – to another dancer, to the space, to the music, or to themselves. Even so-called abstract ballet should offer the viewer at least an impulse that awakens in them the need for their own interpretation, their own narrative.

I needed peace and quiet before the performance

Let's go back to your dancing career. You won the Benois de la Danse award for your role as Armand Duval in The Lady of the Camellias by John Neumeier. In 2015, you ended your dancing career at the Semperoper in Dresden in the role of Chevalier des Grieux in MacMillan's Manon. Did you have any other favorite roles?

Armand was definitely one of them. So was the role of Vaslav Nijinsky in the ballet Nijinsky, which John Neumeier created specifically for me. I also really liked the role of Kosti in the ballet Die Möwe (The Seagull), based on Chekhov. I was just a little disappointed that I broke a bone in my hand four days before the premiere and had to have surgery right away. To this day, I still have three screws in it and a scar.

I also enjoyed Neumeier's production of Peer Gynt, where I had about eleven different roles and costumes. But I also danced other distinctive characters at the Semper Opera in Dresden – for example, Romeo in a modern version of Romeo and Juliet, which Stijn Celis created for me. I remember that role with great joy; I completely immersed myself in it and forgot myself.

I also enjoyed dancing in the ballets of Mats Ek and William Forsythe... In Hamburg and Dresden, the repertoire was truly exceptional and there were countless roles. I loved them all – even the smaller ones.

What was your day like before a performance? Did you have any rituals?

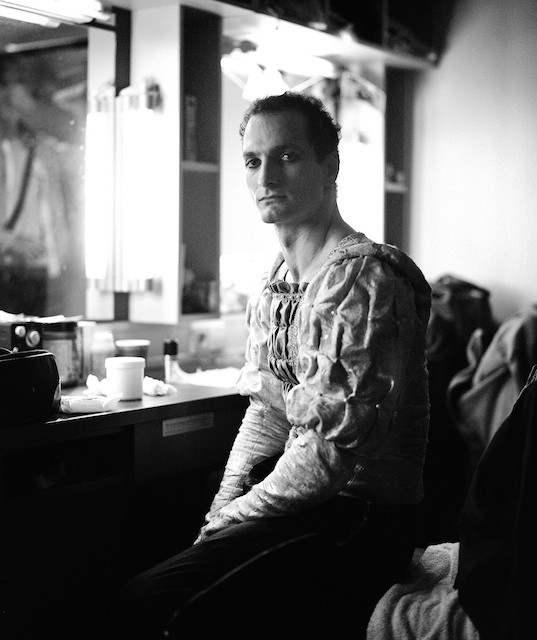

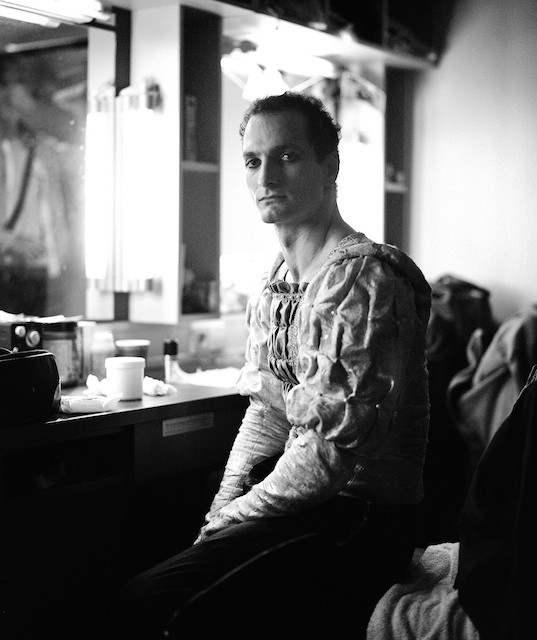

I needed peace and quiet. When we performed in Hamburg in the evening, rehearsals ended at half past one. I liked to lie down for an hour to recharge my batteries. Then I got in the car, drove to my favorite café, had a small snack, and was at the theater two hours before the performance. I took a shower, put on my makeup, prepared my costume, and went to an optional rehearsal with the ensemble.

I always went through the choreography on stage. Before I went on stage, I said to myself: "Don't think you are. You know you are." Over the years, I have learned that only the present moment can guarantee a good performance.

When you finished dancing, the curtain closed, did you go home with a clear head? Or did you think about what went well, what didn't...

Sometimes I just sat in the dressing room and let the experience sink in. Most of the time, joy prevailed, sometimes emptiness. I liked to have a beer with my colleagues, we discussed what went well, and we often had a good laugh. I knew that I had given the performance everything I could at that moment. And if something didn't work out, I started working on it the very next day.

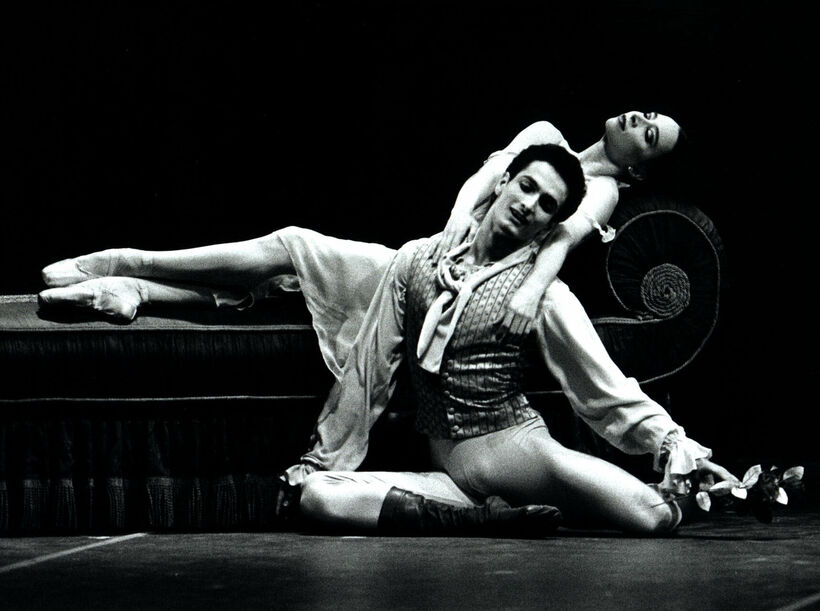

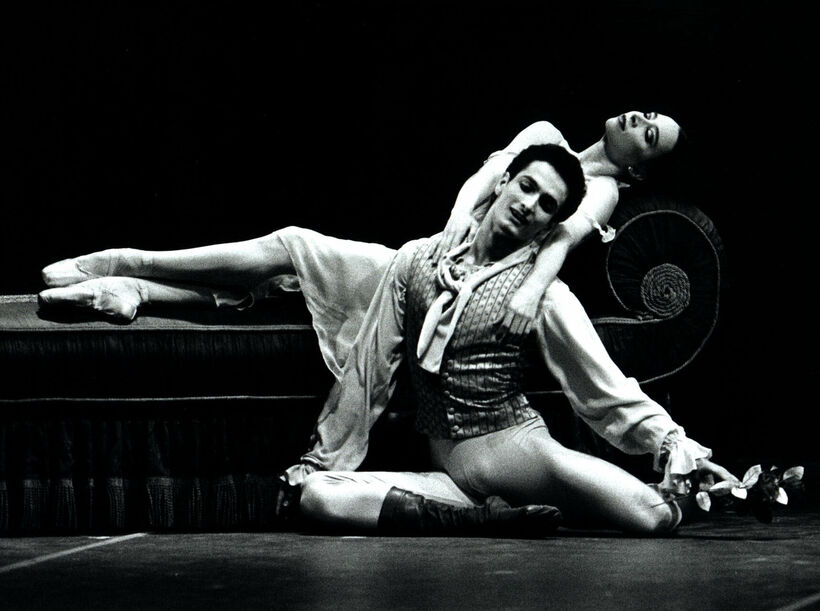

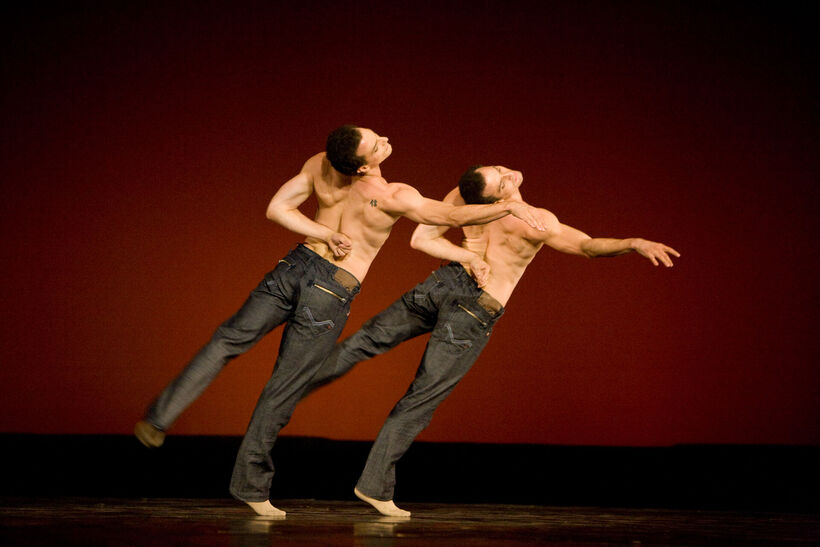

One German critic wrote about you in connection with Swan Lake (Illusions – Like Swan Lake) by Neumeier: "Jiří Bubeníček? He wears jeans, but he's a prince through and through." I don't begrudge him that, but for me you are unforgettable in A Midsummer Night's Dream, with which the Hamburg Ballet made its first guest appearance in Prague. You also had a comic role in As You Like It. Do you like humor?

At the beginning of my career, as a young dancer, I was often cast in comic roles. Probably because I was cheerful, liked to have fun, and seemed carefree. I enjoyed characters like Benvolio, and especially Mercutio—I think he suited me best. Humor is important. I like it when people laugh – maybe it's from my childhood, when they often played with us kids at the circus. Today, I make my children laugh in a similar way.

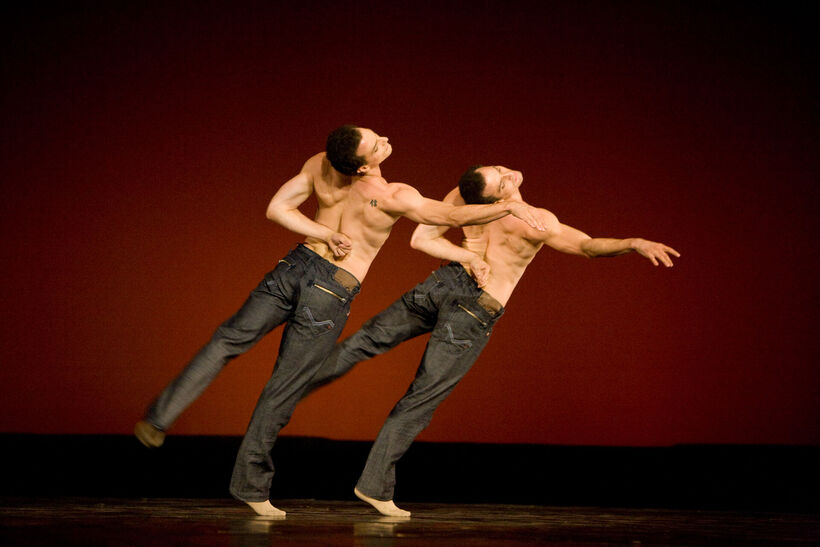

Your performance with Otto in the duet Les Indomptés was fabulous. How did you acquire this piece by Claude Brumachon?

The duet was originally created for the Jeune Ballet de France, but gradually became part of the repertoire of other companies and theaters. I first saw this choreography in Hamburg at the Nijinsky Gala with Manuel Legris and Benjamin Pech. They danced beautifully, and I was completely thrilled by the choreography and music. I knew immediately that I wanted to dance this duet.

First, I approached the assistant choreographer and then Claude Brumachon himself. I was lucky—at the time, I was dating a prima ballerina from the Paris Opera who knew him and helped me contact him. Since the premiere in Copenhagen, which Claude attended in person, my brother and I have danced this choreography at almost every gala around the world. To this day, many people think it was created especially for us. We even won an award for best duet at the Dance Open festival in St. Petersburg.

Brumachon's style of choreography reminds me of the German choreographer Marc Goeck.

You're right. The principle of sudden, almost explosive movement recurs constantly in his ballets. One of his first choreographies was created for the Hamburg Ballet, so I am very familiar with his work. I even went to Munich to see his La Strada. This is my personal opinion, but I think Marco is stronger in so-called abstract things. I didn't really understand his concept at all. Nevertheless, it inspired me, and I told myself that one day I would create my own version.

Do you project your emotional memories into your choreography?

Each of my choreographies bears the imprint of my presence, perhaps even little hidden secrets. In La Strada, there is a part that talks about twins. Circus, twins... That topic touches me personally. There was a time when I had a hard time dealing with it. For example, I didn't like it when my brother and I were walking down the street and children pointed at us, saying we looked alike. There were other situations that bothered me at the time. Today, I take it in stride.

As a freelance artist, can you afford to turn down work?

The most important thing for me today is who I work with. When an ensemble approaches me, it has to be interesting and inspiring to me. I have a family and two children, and if the work isn't stimulating enough, I give preference to them.

What are you working on now? We met right after your visit to Czech Television in Kavčí Hory...

I don't want to reveal too much about this meeting yet, it was the first one, but it looked promising... I was approached again by the management of the National Theater in Košice, where I will prepare a new version of the ballet Le Corsaire together with Nadina. I managed to get set designer Giovanni Carlucci, who already worked with me onCarmen at the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma in Rome, to collaborate with me again.

At the same time, the ballet Doctor Zhivago, which I created together with my brother for the National Theatre in Ljubljana, will be revived. In addition, I am preparing the first ballet festival in Prague called Prague on Point. I am also very much looking forward to working with a famous actor, whose name I will not reveal yet, and together with Pavel Juráš (editor's note: director, set designer, theorist, critic) we are preparing a new book.

How fulfilling are the galas you organize? Do they distract you from your artistic immersion?

On the contrary, I have the opportunity to present my own choreography and original projects. For more than 15 years, I organized all the foreign tours of our Les Ballets Bubeníček ensemble.

I am involved in the entire production side – from the financial budget to graphics, websites, writing texts, and editing music. Today, I actually do what would normally be done by a whole team of people in a theater.

Do you enjoy dance performances as a spectator, without professional "distortion"?

I do. But it depends on how much the production or performer can draw me into the work. When they succeed, I stop evaluating and am happy to forgive all minor transgressions. On the contrary, when the performance doesn't work, I start to notice shortcomings – dance technique, lighting, details that would otherwise remain in the background. Let me return to the aforementioned gala performance for the 80th anniversary of the Dance Conservatory. I saw a duet from Neumeier's Spring and Fall with music by Antonín Dvořák. I danced it myself thirty years ago, and I still remember every step and everything I felt. And now, suddenly, I missed the dynamics on stage, the harmony with the music, but above all, the reason why each movement is done! When I miss these ingredients, the choreography suddenly seems boring, old... Nevertheless, I try to enjoy every performance. I know very well how much work, effort, and energy goes into it.

You studied pedagogy at the Palucca Schule. Is it your second profession besides choreography?

I started studying at the Palucca Schule during the COVID pandemic, and I learned a lot in three years. I completed my studies in English, and although I speak English fluently, academic writing in a foreign language was a new challenge for me. Today, I am glad that I became a Master of Arts in pedagogy and can confidently pass on my experience to young students and dancers, for example in my masterclasses.

Who is your most important friend?

Definitely my wife. We understand each other not only in our personal lives, but also in our artistic lives. We support and inspire each other and have a deep understanding between us, which is extremely valuable to me.

You once said that it is important for you to live every moment in harmony with the universe. What is this universe in which you find support and faith?

I believe in truth and goodness. What a person radiates always returns to them, just in a different form. But the question is, what is the universe actually? Is it really the sky above us full of stars, or the space inside each of us?

Going back to the beginning of our conversation, to Neumeier, dance is a great passion for him. What is it for you

For me personally, dance is a way of being – the language of the soul. It is part of my identity, and when you express yourself, breathe, and live through it, it becomes your life.

Labuti_ho jezera_Photo_Klemens Renner.jpg)

Jiří Bubeníček (born October 7, 1974) is an internationally renowned choreographer. During his nearly 25-year dance career, he was one of the best ballet soloists in the world. Choreographer John Neumeier created a number of roles for him at the Hamburg Ballet (Hamburg Ballett), among which his portrayal of the famous dancer Vaslav Nijinsky in the production Nijinsky became legendary, earning him ovations even at the Paris Opera.

Jiří Bubeníček danced with the Hamburg Ballet from 1993 to 2006 (becoming principal dancer in 1997), after which he became principal dancer with the Semperoper Ballet in Dresden. Here he danced a large number of roles in works by well-known choreographers (e.g. Petipa, Fokine, Balanchine, Crank, MacMillan, Kylián, Inger, Forsythe, Godani, Celis), including choreographies by the company's artistic director Aaron S. Watkins. He has performed as a guest soloist all over the world: for example, at the Paris Opera, he danced the role of Armand in Neumeier's ballet The Lady of the Camellias with the most prominent ballerinas of the time. For this role, he received the prestigious Benois de la Danse award (2002). This is one of many awards in his career, which also include the Espèces prize at the Prix de Lausanne international ballet competition and the Mary Wigman Prize, awarded by the Semper Opera in Dresden.

In 1999, Jiří Bubeníček began to devote himself to choreography alongside his career as a dancer. The list of his choreographic works includes over seventy titles, ranging from dance miniatures and more abstract choreographies to full-length narrative ballets. He has gained international recognition primarily as a choreographer and storyteller. His successful productions include the ballet Romeo and Juliet (Jiří Bubeníček received the highest number of audience votes, for which he won the Boris Papandopulos Award for the best performance of the 2021/2022 season), Rusalka (2017), Anita Berber – Queen of the Night (Anita Berber – Göttin der Nacht, 2016), Doctor Zhivago(Doctor Zhivago, 2016), The Piano (The Piano, 2018), The Trial (Processen, 2019), and Cinderella (Cinderella, 2019). For his ballet Carmen (2019), the choreographer was awarded the Europa in Danza prize, one of many he has received over the years.

In 2017, he was honored with the Silver Medal of the City of Prague, an exceptional award from his native country.

Labuti_ho jezera_Photo_Klemens Renner.jpg)