As the British dance scene becomes engulfed, at this time of year, by productions of The Nutcracker, I’d like to take this opportunity, in my second Letter from London, to look back at some of the performances I saw during the summer and autumn. This latest Letter will not be exhaustive, nor will it cover every dance company that has appeared here, but it does take us out of the capital for a brief look at some of the dance companies performing on tour.

Matthew Ball and William Bracewell in Against The Tide at the Royal Opera House. Photo: Tristram Kenton

Summer highlights

Two events during the summer brought me considerable pleasure. First was the annual matinée performance at the Royal Ballet and Opera in July by The Royal Ballet School (RBS), which next year celebrates its 100thbirthday. Now under the artistic direction of Iain Mackay (a former principal with Birmingham Royal Ballet), it was, quite simply, the best show by the RBS in years, and what was particularly heartening was to see how the young students rose to the challenge of dancing what are considered cornerstone works in The Royal Ballet’s repertoire – Act III of Marius Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty, and Frederick Ashton’s Les Patineurs. It was a performance of high professional standards, with Amos Child, Aurora Chinchilla, Matteo Curley-Bynoe, Yasemin Kayabay, Fabrizzio Ulloa Cornejo and Wendel Viera Teles Dos Santos especially impressive.

Second was National Ballet of Japan, who made a triumphant London debut during July, also at the Royal Ballet and Opera, with a new production of Giselle staged by its artistic director Miyako Yoshida (an audience favourite when she danced regularly with both Birmingham Royal Ballet and The Royal Ballet) and British choreographer Alastair Marriott. The production was good – a traditional version of this classic from the Romantic age – and the dancers were notable for their dedication, unity of style and strong technique. The performance I saw was led by the impressive Yui Yonezawa, a sweet Giselle, who danced lightly, precisely, prettily and, above all, acted the role with sincerity. Now that London no longer plays host to ballet companies from Russia during the summer months, this may be the perfect opportunity for a swift return visit by National Ballet of Japan, next time with a wider and more varied repertoire.

Sadler’s Wells and London City Ballet

Sadler’s Wells hosted a series of familiar names and companies over the autumn months, including Acosta Danza, Akram Khan Company, Birmingham Royal Ballet, Sharon Eyal, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Nederlands Dans Theater and Hofesh Shechter. I was sorry to miss the Sadler’s Wells debut of Cassa Pancho’s brilliant Ballet Black (a long over-due event, if ever there was one), but in September I enjoyed immensely the second season of the newly relaunched London City Ballet (LCB), a company resurrected in 2024 by choreographer Christopher Marney. The ensemble of 14 dancers (including Alina Cojocaru, Alejandro Virelles and Joseph Taylor) tours the UK and abroad extensively (as did the original LCB), and one of Marney’s most admirable ambitions is to restore to the stage one-act or small-scale works by great choreographers that are in danger of vanishing from the repertoire. Last year, LCB performed Kenneth MacMillan’s Ballade after an absence of 50 years, and at Sadler’s Wells this autumn, the company danced George Balanchine’s beautifully crafted Haieff Divertimento, as well as the first staging by a British company of Alexei Ratmansky’s marvellous, vivid Pictures at an Exhibition. It has been thrilling to see how much Marney has achieved with LCB in such a short period of time, and it is pleasing to learn that he has equally exciting plans for the company in future seasons.

On the road with Gary Clarke Company and English National Ballet

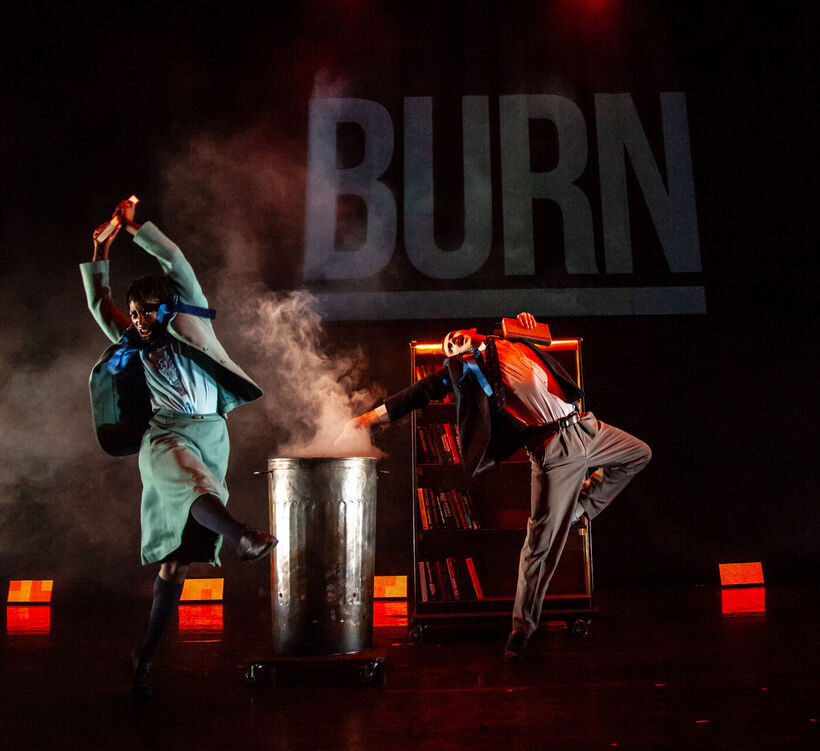

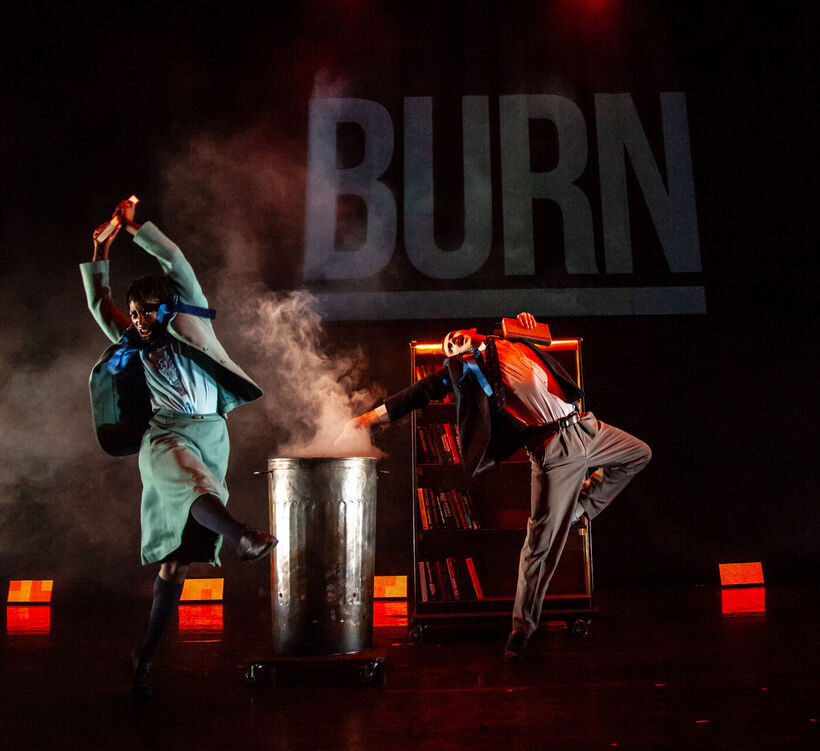

Of course, a great deal of dance activity in the UK takes place away from London, as all the major ballet and contemporary dance companies – with the notable exception of The Royal Ballet – tour the regions. One of the most exciting, as well as the most politically engaged, is the Gary Clarke Company. Clarke has now completed his trilogy of works exploring the impact on the UK during the 1980s of Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative government. Starting with COAL, a thought-provoking piece that took its inspiration from the lives of local mining communities during the industrial action taken by the National Union of Miners in 1985, it was followed by Wasteland, a reflection on 1980s drug culture and its effect on unemployed working class families.

The concluding Detention, which I saw at Brighton’s Corn Exchange in October, takes as its central theme Section 28, a controversial and discriminatory law introduced by the Thatcher government in 1988 at the very height of the AIDS crisis, which prohibited local authorities (and therefore schools) from “promoting homosexuality” or teaching “the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”. Once again, Clarke scores highly with a work that is angry, but one that also skilfully evokes the fear and prejudice suffered by members of the Queer community, as well as their personal resilience and resistance. Clarke’s visceral, punchy, highly physical choreography is simultaneously heartbreaking, horrifying and ultimately redeeming. The production should be touring again in 2026.

West of Brighton, along England’s South Coast, lies the city of Southampton, where English National Ballet (ENB) was on tour at the Mayflower Theatre at the end of November. The company were performing Kenneth MacMillan’s staging of Marius Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty, which was first unveiled, coincidentally, in the same theatre 20 years ago. ENB has previously presented the production virtually complete, but new artistic director Aaron S Watkin has decreed the ballet needs to be made “more accessible for today’s audience”. In consequence, The Sleeping Beauty has been savagely cut by about 30 minutes in total. I might have felt less dismayed than I did if the standard of classical dancing had been outstanding, but much of the soloist and corps de ballet work was competent rather than inspiring. However, Ivana Bueno made a very promising Princess Aurora, with a wonderful “lift” to her jumps, and some superbly held balances during the Rose Adagio. In addition, Thiago Silva was a wonderfully airborne Blue Bird, but best of all was Junor Souza, who gave a riveting account of the wicked fairy, Carabosse.

At the Royal Ballet and Opera

The Royal Ballet’s 2025/26 season opened officially in the Linbury Theatre in September with the London premiere of Jonathan Watkins’ two-act dance version of Christopher Isherwood’s novel A Single Man, which was first seen at the Manchester International Festival in July. Watkins has a good track record of adapting books into successful dance works, most notably his compelling staging of George Orwell’s 1984 for Northern Ballet, but A Single Man was disappointing, only coming to life during the duets choreographed for the gay lovers, George and Jim, in which they express their feelings of desire and companionship before Jim’s death, and then in George’s wrenching anguish after their separation. The roles were danced with electric intensity by Edward Watson and Jonathan Goddard.

On the Main Stage of the Royal Opera and Ballet, the season proper opened with a revival of Christopher Wheeldon’s full-length Like Water for Chocolate. No favourite of mine, I decided to give it a miss, but attended instead a very welcome revival of Frederick Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée. Absent from The Royal Ballet’s repertoire for nine years, many of the leading roles were newly cast, which meant characters, such as Widow Simone, Farmer Thomas, and his son, Alain, were being portrayed by artists with little experience of appearing in character roles. Either under-powered, or way over the top, this new generation need more time to find their own way into these roles, but at least, at the two performances I attended, the Lise and Colas of Anna Rose O’Sullivan and William Bracewell, and of Francesca Hayward and Marcelino Sambé, were taken by dancers completely at home in Ashton’s dazzling, warm-hearted choreography.

Fille, which returns to the repertoire again in May 2026, was followed by an odd triple bill that included Balanchine’s Serenade (much better performed than it had been back in March), the UK premiere of Justin Peck’s Everywhere We Go and the world premiere of Cathy Marston’s Against the Tide. Danced to Benjamin Britten’s Violin Concerto (superbly played by soloist Vasko Vassilev), Against the Tide finds Marston working in a more fluid and lyrical style than usual, and the theme of her ballet appears to be based on the anxieties of the period just before the outbreak of World War Two (when the Concerto was composed), as well as drawing on Britten’s own personal life. Centring around the relationship between two young gay men, Against the Tide was intriguing, if emotionally muted, and I appreciated that Marston had, first, brought Britten’s music back to Covent Garden and, second, that she had the bravery to depict an overtly homosexual relationship on the stage (something her male counterparts at Covent Garden have yet to tackle in any great depth). The dancers were superb, with William Bracewell and Matthew Ball outstanding.

Peck’s Everywhere We Go is a series of dances to music by Sufjan Stevens, performed before Karl Jensen’s beautiful, kaleidoscopic backdrop that changes its patterns and muted colours before our very eyes. Peck’s choreography is fast paced, inventive, sometimes humorous, often virtuosic, occasionally disquieting, and very American in style. It has energy and grace, and is joyous in its unexpected twists and turns. The ballet was danced to the hilt by Luca Acri, Daichi Ikarashi, Sae Maeda, Mayara Magri, Marianela Nuñez, Viola Pantuso and, best of all, Reece Clarke.

Peck’s Everywhere We Go is a series of dances to music by Sufjan Stevens, performed before Karl Jensen’s beautiful, kaleidoscopic backdrop that changes its patterns and muted colours before our very eyes. Peck’s choreography is fast paced, inventive, sometimes humorous, often virtuosic, occasionally disquieting, and very American in style. It has energy and grace, and is joyous in its unexpected twists and turns. The ballet was danced to the hilt by Luca Acri, Daichi Ikarashi, Sae Maeda, Mayara Magri, Marianela Nuñez, Viola Pantuso and, best of all, Reece Clarke.

December coincides, in the UK, with an onslaught of Nutcrackers. Of the five major ballet companies based here, four are dancing the Christmas favourite this year, with only Scottish Ballet the honourable exception. By far the biggest and most elaborate Nutcracker is the one staged by Peter Wright for The Royal Ballet, which has been a mainstay at Covent Garden ever since it was unveiled in 1984. It is a production, in traditional designs by Julia Trevelyan Oman, that, after all this time, runs like clockwork, the highlights being the spectacular growth of the Christmas tree in Act I, and the retention in Act II of Lev Ivanov’s original choreography for the Grand Pas de Deux. The performance I saw on 10th December was led by Mayara Magri as the Sugar Plum Fairy in one of the finest accounts of the role I have ever seen. Musical, luxurious and very grand, Magri danced with a warmth, luminosity and graciousness I have only ever seen equalled before, in this production, by ballerinas of the calibre of Nina Ananiashvili, Fiona Chadwick, Laura Morera and Zenaida Yanowsky. Partnered by the noble Reece Clarke as her Prince, and joined by the lovely Clara of Marianna Tsembenhoi, it was Magri’s outstanding performance in this Royal Ballet production that was relayed to cinemas around the world. Look out for it if you can.