Molnár's Liliom has been adapted into almost every conceivable art form – film (including a version by director Fritz Lang, 1934), radio (a version by Orson Wells, 1939), musical (the Broadway hit Carousel by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, 1945), but also opera and even ballet – in the Czech Republic, it was staged in 2021 by the F. X. Šalda Theater in Liberec, choreographed by Rie Morita.

Molnár accompanied the title of the play with a double subtitle: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel / A Suburban Legend in Seven Scenes. It reveals the dramatic oscillation that is fundamental to the play: the genre of legend associated with the life and death of saints who go to heaven for their miraculous deeds and martyrdom. Molnár's legend confronts life and death, but it is the life and death of a rogue, and Neumeier follows this line with a keen eye. In his version, the drama does not take place in Budapest, but in America in the 1930s, in an amusement park with carousels, acrobats, jugglers, and exotic dancers. The choreographer also added a prologue to the seven scenes.

Molnár's Liliom confronts life and death, but it is the life and death of a scoundrel, and Neumeier follows this line with a keen eye. In his version, the drama does not take place in Budapest, but in America in the 1930s, in an amusement park with carousels, acrobats, jugglers, and exotic dancers.

Lovers from the suburbs

Upon entering the auditorium, we see a curtain with a view of clouds floating across the sky. With the first notes, a tall dancer (John Powers in the first cast, Ole Johannes Slåttebrekk in the second) enters the stage slowly, facing the audience, wearing a long black tailcoat, his face whitewashed, a bowler hat on his head, and colorful balloons in his white-gloved hands. This Man with Balloons, as the choreographer called the inserted character, appears throughout the ballet – he is a kind of Charon who transports the dead to another dimension/underworld. It is he who brings Liliom, who has been dead for sixteen years, onto the stage in the prologue, giving him the opportunity to return from purgatory to earth for one day to perform at least one good deed and thus atone for his sins. The images that follow are initially a retrospective of his life.

It's hard to say what's more of an attraction, the carousel or the cool guy Liliom. Don't the ladies come here just because they hope to be seduced by the notorious seducer? Liliom is a handsome, reckless, cheeky young man who doesn't care about anything or anyone until he meets the waitress Julie, with whom he falls in love and has a child. Julie tells him this news at the moment when he hits her and his violent, aggressive tendencies manifest themselves. Nevertheless, the girl remains devoted to him body and soul... On the same day that Liliom finally finds the love of his life, he loses his job. He takes it hard and decides to take part in a robbery with his accomplice Fric. Somewhat illogically, they rob the owner of the carousel, Mrs. Muscat, who employed Liliom and was his lover, so she immediately recognizes him. Liliom is surrounded by police and stabs himself at the wedding reception of Marie, Julie's friend.

Liliom passes into purgatory, depicted by Neumeier with sarcastic dance exaggeration, where the guilty are judged by a heavenly official. After Liliom confesses that he hit Julie, devils appear and give him a good beating, and the arms of dancers in red costumes wrap around his body like fiery flames. And what will Liliom do after sixteen years in purgatory when the Man with Balloons brings him back to earth, where he meets his now sixteen-year-old son? The father tries to approach him and give him a star, but Louis refuses it. Liliom reaches out and hits his son (in Molnár's original, his daughter).

Attractive visuals

The atmosphere of the 1930s is evoked from the outset by the set design and costumes (based on the graphic design of the posters for the musical Carousel) – light bulbs evoking shining stars hang above the stage, and large glowing wheels reminiscent of fairground attractions descend from above. The costumes, with their subtle color palette, and the musical accompaniment by Michel Legrand (1932–2019) also fit into the period setting. This renowned French composer, conductor, and pianist mixed an orchestral part with elements of classical music and jazz for Neimeier's ballet, so the musicians of the State Opera sit in the orchestra pit and the Top Big Band on a raised platform on stage.

Legrand varies the melodic leitmotif, which is heard for the first time in Liliom's first duet with Julie. Julie is shy, paralyzed by love, and therefore looks clumsy with her arms outstretched and knees bent, unable to give vent to the rush of emotion that is paralyzing her at that moment. Liliom also does not know what to do with himself, and the lovers find their way to each other cautiously, slowly, repeating their variations. In the second half of the production, the musical leitmotif is repeated almost constantly and transforms into endless jazz combinations.

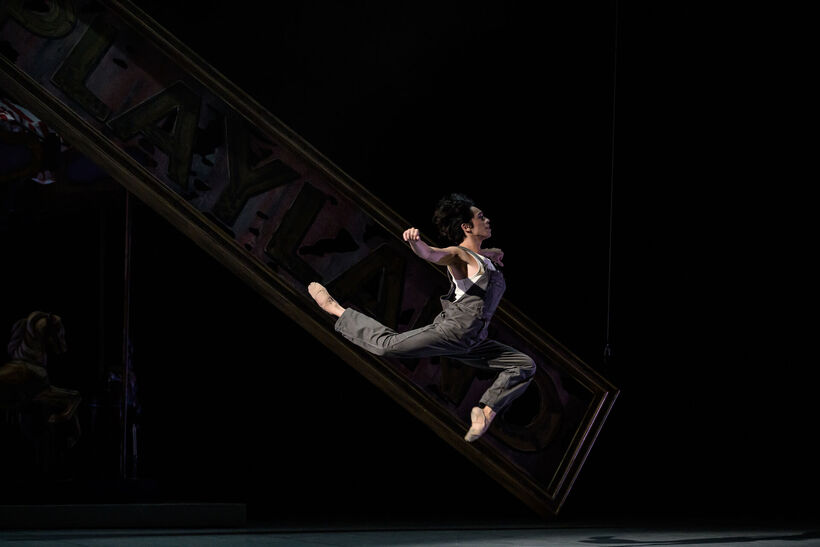

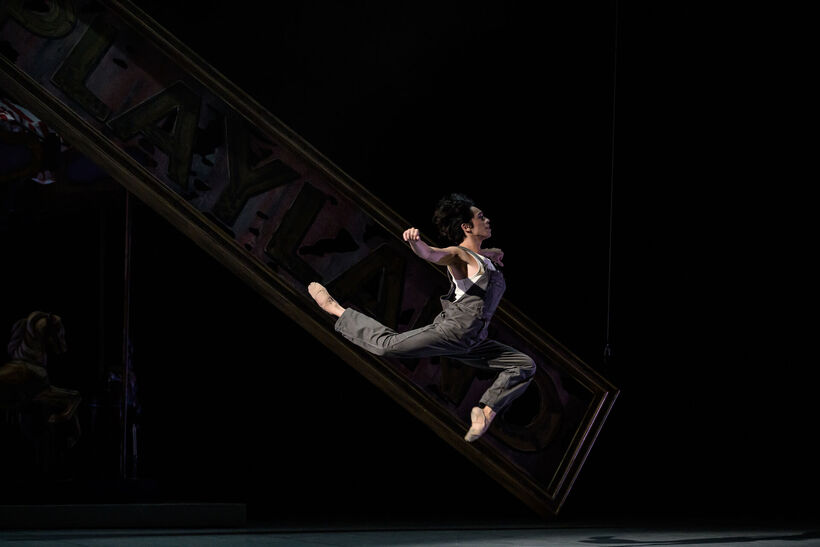

The jazz tuning brings frivolity, lightness, and playfulness to the ballet in the ensemble scenes from the amusement park with a carousel, which here represents a metaphor for the cycle of life, but is mostly not very visible, as it stands hidden in the darkness in the background of the stage. Jazz rhythms do not feature prominently in the choreography, as Neumeier bases both the solo and ensemble parts on neoclassicism, which requires the performers to have precise technique in rotation, jumps, and confident pointe work, all in connection with the events conditioned by the actors' expressions captured in gestures, posture, and facial expressions. Liliom's part contains more jazz casualness, as he makes his disagreement quite clear with a raised middle finger, works significantly with his pelvis, and his variations deviate most from the neat neoclassical form.

In the first cast, Giovanni Rotolo dominated the stage with his charisma in the lead role, wearing black leather pants, a shiny jacket, and a top hat. He is a loud and unmistakable braggart who also shows off his well-developed chest. In addition to his macho attitude, he gradually reveals his other side. He falls in love with Juliet, but does not show his feelings too much. In the end, he appears to be a weakling who runs away from responsibility and commits suicide. His dying body is manipulated for quite some time by his lover Juliet, played by Alina Nanu. Together with Rotolo, they are a well-coordinated duo who master Neumeier's difficult combinations and the required acting details without the slightest problem. Rotolo is a force of nature who does not completely melt even under the onslaught of romantic intoxication; his animalism and directness are credible and effective. He is Liliom, whom you devour with all your senses until the moment Julie is struck... But what then? Although he reenacts his sins in the afterlife and is given the opportunity to do a good deed, his violent nature, where anger overwhelms good intentions, prevails, and Rotolo realizes his failure.

In the second cast, the main roles are danced by Paul Irmatov and Aya Okumura, who balances her partner's uncertainty with her gentle and gradually escalating performance and technical refinement. Irmatov throws himself into the role with great determination and full steam ahead, but he fails to bring out the point of the gestural and acting situations, and as a result, his Liliom lacks a balanced drive throughout the more than two-hour production. Kristina Kornová and Kristýna Němečková alternate in the role of Mrs. Muscat. Kornová plays more on the string of a calculating bitch who wants to control Liliom, possess him, and does not tolerate his relationship with Julie under any circumstances. She flirts with Liliom, offers herself to him, and enjoys eroticism with him in a hedonistic way. Němečková shows more warmth and less pragmatism towards her subordinate. Each of the performers projects a diverse and nuanced range of emotions into their roles. Thanks to them, Liliom is not only a visually captivating production, but also a work in which John Neumeier's thoughtful touches can be seen.

How to interpret violence?

Neumeier seeks justification for his hero in scenes that are multi-layered in terms of direction and dramaturgy, yet the production comes across as a bittersweet story. The characters' motives and emotions do not reach the audience with the urgency that the choreographer intended. The question is whether important nuances that were present in Hamburg were lost in the staging.

A superficial reading of Molnár's Liliom, and ultimately Neumeier's ballet, may lead to the conclusion that it is an apotheosis of domestic violence, as Liliom is unable to express his love in any other way than through violence. The relationship between Liliom and Julka (Molnár sticks to argot), these strange "Veronese lovers" from the suburbs, is ambivalent. One explanation—albeit one that is of little interest for the production itself, as it is purely alibistic—is the fact that Molnár intended Liliom as a kind of apology (even self-defense) for how rudely he behaved toward his first wife and what a bad father he was (Molnár's biography intersects with Liliom in his attempted suicide, which in the author's case was unsuccessful). It is up to you whether you accept this argument.

If we consider the fact that Neumeier set the story in the 1930s, when women began to reject their submissive position in relationships and their role as obedient creatures who adored their men in all circumstances and looked up to them with boundless respect, his interpretation is even more difficult to accept. At the turn of the 1920s and 1930s, the status of women was beginning to be discussed publicly! One example is the French writer and philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, who at that time saw herself as an independent, strong personality who rejected submissiveness and convention, thereby breaking the social taboos of the time and disrupting traditional stereotypes about the role of women (the opposite sex) in society. In addition, American playwrights at the time mostly shared an aversion to sentimental melodrama. Seen in this context, the catharsis that Neumeier, in agreement with Molnár, sees in forgiveness and boundless love in all circumstances is difficult to digest (at least for me).

The conclusion of the play, as well as the ballet, is extremely provocative in terms of interpretation, not to mention the (hardly unintentional) disproportion in the dramatic structure, where the turning point of "purgatory" in Molnár comes after almost ninety-five pages of typescript, while the dénouement itself is actually rushed, impulsively, in just ten pages. Although both Liliom and the heavenly guards wring their hands over the final act, the last lines of Julia and Luisa suggest that, paradoxically, it will remain a "beautiful memory" for them.

Neumeier's ballet has the same effect. Although Liliom tries to suppress his aggression, he cannot control his emotions and cannot bear rejection... Even though Molnár became a renowned author, many critics reproached him for the cheapness of his ideas. Neumeier did not accept this and sought a deeper justification for the characters' actions, yet even his dance adaptation remains a lengthy romantic melodrama with metaphysical embellishments.

Written from the first premiere on October 24, 2025, and the performance on October 26, 2025, at the Prague State Opera.

Liliom

Choreography and costumes: John Neumeier

Music: Michel Legrand

Set design: Ferdinand Wögerbauer

Lighting design: James French, John Neumeier

World premiere 2011, Hamburg Ballett