Taking place exceptionally at Teatro Argentina in central Rome, the two-act piece brought together acclaimed dancers from Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch – Nazareth Panadero, Héléna Pikon, Julie Shanahan, and Fernando Suels Mendoza, along with Doug Letheren –, Paris Opera’s Antonin Monié, and members of Øyen’s company Winter Guests (Enoch Grubb, Pascal Marty, and Meng-Ke Wu). Combining movement, original text, and live cinematic projections by Mathias Grønsdal, Øyen and his creative collaborators Daniel Proietto and Andrew Wale offered a free, contemporary interpretation of Sophocles’ timeless tragedy.

Alan Lucien Øyen’s Antigone: Between Myth and Invention

This summer, Teatro di Roma launched the first edition of the Teatro Ostia Antica Festival (23–26 July 2025), renewing its collaboration with the open-air Roman theatre of Ancient Ostia. Under the title Il senso del passato (“The Meaning of the Past”), the festival hosted five performances inspired by the myth of Antigone that reimagined Sophocles’ classical masterpiece for modern audiences. Among them, the world premiere of Antigone by Norwegian choreographer Alan Lucien Øyen stood out.

The anchor points in the myth

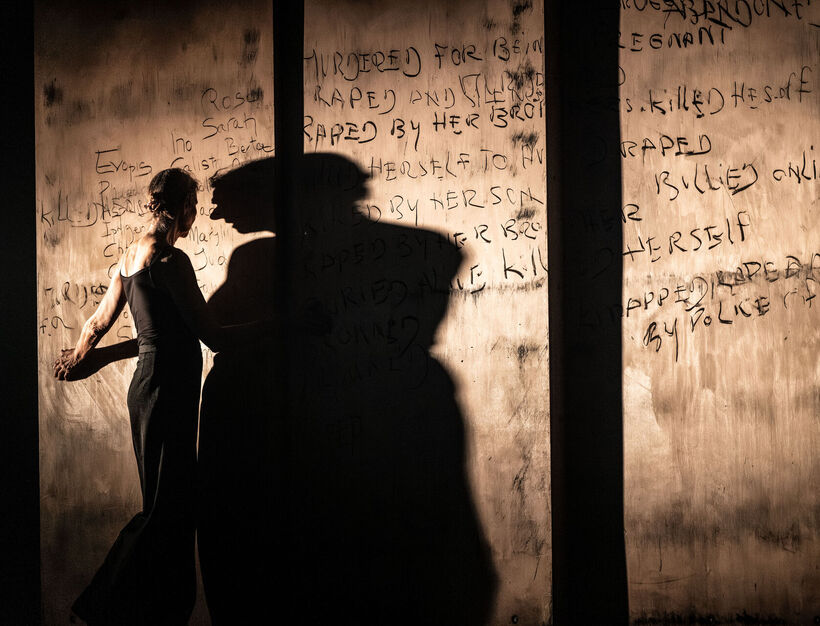

On stage, a woman’s “lifeless” body hangs in the air, her shadow casts against one of the seven L-shaped panels of the set design, evoking the seven gates of Thebes – an immediate, stark revelation of the tragedy’s end. A blind man (the soothsayer Tiresias, although the characters remain unnamed throughout Øyen’s version, leaving the audience to guess them) is led across the stage by a guide who narrates the imagined ruins of Thebes or any other war-torn city. Description and invention blur, evoking a portrait of a destroyed city, Gaza, even.

Enoch Grubb and Antonin Monié, momentarily embodying Antigone’s brothers (Eteocles and Polyneices), clash in a gripping, part-fight, part-embrace duet beginning with an arm-wrestling gesture that is fused with acrobatic movements, filling each other's negative space. As the struggle ends, Polyneices gasps, “I can't breathe” – George Floyd’s last words – echoing the violence of state power. Later, in a sudden change of orientation of one of the L-shaped panels, Polyneices, now the corpse of a dead “traitor”, delivers his monologue upside down, as if fallen and exiled from Thebes’ walls. In this paradoxical and powerful scene, he shares how it feels day by day to decompose further. In a shift of mood, Nazareth Panadero engages in a surreal dialogue with “Alexa,” personified by Doug Letheren, who answers her metaphysical questions – such as “Where is the door to the underworld?” – with an eerie, AI-style calmness.

The poetic use of space and set design is key to Øyen’s visual language. The versatile L-shaped panels designed by Åsmund Færavaag are manipulated fluidly by the performers: they form walls that include or exile, a bed and a rooftop. With a simple rotation, they expel Antigone and Polyneices from the city or protect intimate exchanges between bodies. Assisted by Martin Flack’s light design, these transformations mirror Øyen’s imaginative visual storytelling – also reflected at both ends of the two acts respectively in the evocative burial of Polyneices and the futile attempt of Creon’s son Haemon, who is desperately in love with Antigone, to reassemble rose petals, a gesture mourning life irretrievably lost.

While Act I loosely follows recognisable fragments of Sophocles’ plot fused with inventions, Act II departs into freer, more abstract territory. Evoking the cave where Antigone is imprisoned for defying Creon for having buried her brother, this part reconnects with the myth towards the end of the piece through four clearly stated words: “shame,” “justice,” “incest,” and “honour”, traced in chalk on the back of Fernando Suels Mendoza. For Øyen, these are the core tensions of the tragedy, distilled into a single written statement – although the central dilemma between human law and conscience and the conflict between resistance and state power, the core ideas of the original plot, feel underdeveloped.

Øyen’s choreographic language blends dragging steps, off-balance tilts, lifts, and transportations of fixed positions in space by the whole ensemble, creating a sense of collective flow. At times, the skilful choreography is juxtaposed with soft, Duncan-style gestures performed under a soppy soundscape that shifts the spirit of the tragedy. In one of the initial dreamlike sequences, the nine performers dance gently in a circle – light as air, yet almost naïve. This sequence returns at the end of the piece’s two-hour duration, echoing both fragility and “mechanicalness”, expressivity and constraint.

Guided by Øyen’s continuous attempts to bridge past and present, Shanahan’s repeated phrase “My name is…”, concluding each time with the name of a different woman, becomes a roll call of women activists, martyrs, and mythic figures – from Iphigenia to Maya Angelou. This idea follows Øyen’s vision of the plural profile of Antigone, further strengthened by the embodiment of Antigone’s character by all the female cast members at different moments of the piece. While powerful, this generalisation flattens diverse women’s histories into Antigone’s singular persona, weakening the piece by overextending its purpose and potential. A similar issue arises in the interlude leading to Act II, where Shanahan demonstrates the hand signal for women in danger when they are unable to speak. Though this scene is important and didactic, it frames Antigone as a victim – contradicting her original role as a conscious, defiant revolutionary woman with the freedom to choose death over submission.

Øyen bravely reimagines a classic through additions and extensions, omissions and inventions, superimposed characters, re-orderings and contemporary references in the form of the physical poetry found in dance theatre. In his attempt, he is supported by a compelling and well-connected cast, though the majority seem to be haunted by the legacy of Pina Bausch. It would be interesting to see these dancers, rich with embodied history, eventually exploring – and leading us as audience members – into truly uncharted territory.

Written from the performance of the 23 July 2025 at Teatro Argentina, Rome.

Antigone

Direction/choreography: Alan Lucien Øyen

With Enoch Grubb, Douglas Letheren, Pascal Marty, Antonin Monié, Nazareth Panadero, Héléna Pikon, Julie Shanahan, Fernando Suels Mendoza, Meng-ke Wu

Creative collaborators: Andrew Wale, Daniel Proietto

Set: Åsmund Fæarvaag

Costume: Stine Sjøgren

Light: Martin Flack

Sound: Gunnar Innvær

Technical manager: Chris Sanders

Stage manager: Daniel Hones

Wardrobe manager: Anna Lena Dresia

Executive producer: Essar Gabriel

Producers: Ornella Salloum, Syv mil v/ Tora de Zwart Rørholt / Ingrid Saltvik Faanes

Still photography: Mats Bäcker

In co-production with Fondazione Teatro di Roma, The Norwegian Opera and Ballet

Premiere: 22 July 2025

ph Mats Bäcker.jpg)