Like most 19th-century melodramas, the plot of Paquita is a little underwhelming and requires a healthy dose of deux ex machina to spice things up. But thankfully, the ballet boasts more than a thin storyline about its titular character, who was kidnapped as a child and later reunites with relatives in a surprise (sort of) twist that allows her to marry her first cousin (yuck!). Not to worry, the ball in the marvelous second act is such a marathon of uninterrupted dancing that any qualms about consanguinity are instantly forgotten. There are ensemble dances, a complex polonaise expertly performed by children of the POB school, followed by still more generous ensemble dances, variations, and a remarkable Grand pas. Wearing shades of deep blue, maroon, and golden yellow, dancers sweep across diagonals and circular formations that frame their chiseled footwork and musical turns. The complex layering and patterns featured in Paquita, if historically accurate, appear to anticipate the structural compositions of Balanchine’s Theme and Variations (1947), or even Busby Berkeley’s dazzling water ballets of the 1930s.

Form Over Function? French and Canadian Ballet this Autumn in Paris

Seeing the Paris Opera Ballet’s Paquita on 18 December felt like something of a Christmas miracle. Since opening night on the 5th, the ballet’s holiday run has been repeatedly disrupted by strikes, an increasingly common scenario every December. This year, the dancers are attempting to renegotiate salaries, arguing that their performance preparation time is uncompensated. While discussions with company management are still underway, audiences who are lucky enough to catch Paquita between cancellations will likely revel in what William Forsythe has called a proto-Balanchine ballet.

Pierre Lacotte’s 2001 reconstruction, which the company asserts is equal parts archaeology and invention, is exemplary of the French style in which the ballet was first created in 1846 by Joseph Mazilier (and then later restaged in Russia by Marius Petipa in 1881). While only fragments of the original production survive through notes and eyewitness accounts, Lacotte’s extensive knowledge of the lines and placement of 19th-century French ballet confers a stylistic consistency throughout the staging. Among an exceptional roster of soloists, the Grand pas dancers Hortense Millet-Maurin and Elizabeth Pardington are especially noteworthy. Both are recent graduates of the POB school and embody the French style with impressive musicality and precision.

One of the benefits of attending POB seasons is observing the diversity of the company’s repertoire, creating visual connections across eras and styles. The intricate geometries of Paquita, for instance, resonate with the season opening of William Forsythe’s works Rearray and Blakeworks I in October. The former, originally created for Sylvie Guillem and Nicholas Le Riche in 2011, has been reimagined in 2024 as a trio. The casting showcases one of the company’s most versatile ballerinas and its newest étoile (as of 28 December), Roxane Stojanov, alongside veteran performers Loup Marcault-Derouard and Takeru Coste. The trio hurtle through Forsythe’s demanding choreography, pouncing and reaching with tender ferocity. Multiple pairs of arms fan out like Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, extended from behind one body. The illusion is shattered when dancers break apart, like exploding atoms, soaring through space. Stojanov in particular excels at Forsythe’s idiosyncratic balances and shifts in weight, sinking into the movements with pleasure.

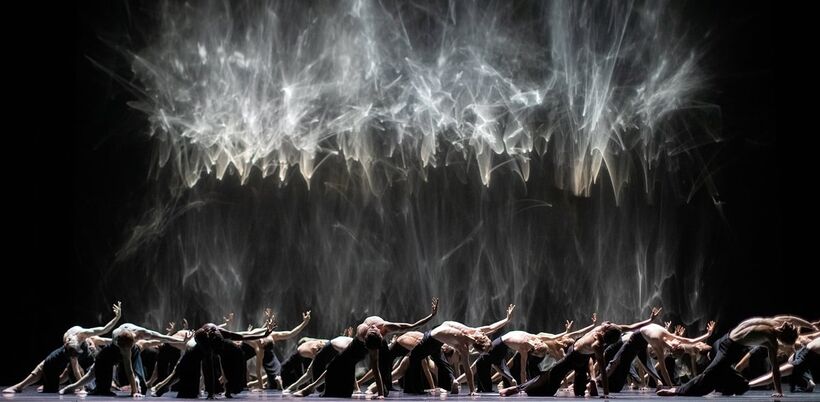

Similarly, Blakeworks I is a Forsythian take on the French style, having been created as an homage to the company’s heritage. Like much of the American choreographer’s repertoire, however, there’s a playful deconstruction at work that rearranges familiar elements, including compact footwork, into surprising patterns and stylised extremes. With a cast of 24 dancers all dressed in sky-blue practice wear, the stage comes alive with multiple actions. There are numerous movement compositions unfolding over every inch of space, not unlike Paquita (whose Grand pas Forsythe openly adores). Set to the electro-pop crooning of James Blake, arms pummel, torsos jut forward and legs lunge. As with Stojanov in Rearray, étoiles Léonaure Baulac, Hugo Marchand and sujet Hohyun Kang stand out for both their technical mastery and sensual enjoyment of the choreography. While Forsythe looks different on every company; the POB perform his work with an elegant sense of attack and infectious enthusiasm.

Between runs of Forsythe’s work and Paquita, the POB presented Mayerling for the second time in two years. Zuzana Rafajová reviewed the production in November for Dance Context Webzine (see here).

Contemporary Canadian Ballet

Performances by other classical companies in Paris are infrequent, making the National Ballet of Canada’s tour a much-anticipated event this autumn at Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Unfortunately, the lackluster triple bill failed to showcase the troupe at its best. While it was an understandable choice to feature living Canadian choreographers during an international tour, much of the work seemed dated or overly bombastic. Even Crystal Pite, a perennial favourite with Parisian audiences, appeared over the top with a gloomy visual scheme and dramatic music. Her well-received Angels’ Atlas (created on the company in 2020) that closed the evening, felt more like a new age mass of collective lunging and baggy fabric than it did an insightful group piece. The audience, however, didn’t seem to mind and burst into prolonged applause.

Choreographically, the evening’s most promising title was James Kudelka’s opening piece, Passion. As the National Ballet of Canada’s artist in residence, his recent ensemble work is an experiment in form set to Beethoven’s Concerto for Piano in D. A group of five women in long pink tutus make up a small corps de ballet, while a neoclassical couple in violet and blue join the stage, completed by two classically-dressed couples. Independent yet sharing the stage, multiple ballets unfold, each performed in a different movement style. Passion is an interesting experiment that requires some tricky spatial negotiations for the dancers but fails to live up to its title.

Sandwiched the middle of the programme, William Yong’s Utopiverse is heavy on effects through ostentatious sets and projections in a sci-fi ode to Paradise Lost. The dancers – clad in embellished nude leotards and short bodysuits – twist and extend in spindly wave-like patterns, as contemporary choreographers are wont to do with ballet dancers. Imagine a male partner pulling the leg of a lithe female performer, stretching it to capacity. As her leg rises, she melts into an arched back bend. All the while, the stage effects are whirling in the background, competing with the large ensemble of dancers and Benjamin Britten’s cyclical score. There is no synthesis between them, leading to sensorial overload in this always busy performance. Will humans find the light again? With so much bling, they couldn’t miss it, but this outcome feels a bit dystopic.

While the Canadian company deserves to be evaluated based on its own merits, I can’t help but proffer a comparison. Unlike Paquita or Forsythe’s Blakeworks I and Rearray, the National Ballet of Canada’s mixed bill lacked the overall sensuality and playfulness of the POB’s season thus far. Although the story of Paquita is paper thin, and there is ostensibly no “message” in Forsythe’s work, the innovative forms that these ballets sculpt in space invigorate the imagination and enliven the senses, offering audiences the freedom to experience and think differently outside of everyday tropes. Beleaguered by establishing an aura of gravitas through illustrative music and motifs, the Canadian company’s artistic direction didn’t place its trust in movement or the dancers, relying instead on artificial constructions of what “serious” dance looks and sounds like. It’s a pity that the skilled performers weren’t given a better opportunity to showcase their artistry.

The above article is based on performances attended at Palais Garnier on 9 October (Blakeworks I and Rearray) and on 18 December (Paquita), as well as at Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on 15 October (National Ballet of Canada).